John Sculley’s childhood was the antithesis of Steve Jobs’. His father was strict and had impossibly high standards for his son.

Sculley attended St. Marks, an exclusive private boarding school made up of blue blooded Northeasterners. While there, he succeeded socially and academically, becoming the captain of the soccer team and earning impeccable grades at the same time.

Being sociable was not easy for Sculley, however, and he feared it. He had to train himself to be sociable. He says in his autobiography, Odyssey, that he decided that he would overcome his stutter and become an inspiring speaker, and he did.

To learn appropriate body language during speaking, he went to movie after movie, studying the actors’ poses, committing them all to memory.

It worked. Throughout his career, his speaking skill would be commended, though it was not perfect. He was nervous in crowds and recoiled at being touched. He often sat by himself in the Apple cafeteria eating his peanut butter sandwich until some merciful employee joined him.

After St. Marks, Sculley studied at Wharton, and he eventually married the daughter of the chairman of PepsiCo, Don Kendall. The two soon divorced, though Sculley maintained a close relationship with his former father-in-law, who gave him a job managing PepsiCo’s struggling Brazilian snack division, which soon became the most profitable division in the southern hemisphere.

Marketing

Sculley thrived in the straight-laced Pepsi atmosphere and quickly climbed the corporate ladder. He became the youngest president of the beverage division. It was in this position where he shined. He launched two major advertising campaigns that would characterize Pepsi’s marketing strategy for three decades.

The Texan Pepsi bottler’s association started a guerrilla ad campaign to combat the stranglehold Coke had on the market. It was a blind taste test called “The Pepsi Challenge” where Pepsi would offer consumers samples of Coke and Pepsi, then ask which one they preferred. Pepsi almost always won. The bottlers succeeded in capturing market share from Coke, and Sculley took the campaign national (and eventually international), where it was very well received.

Another Sculley-initiated campaign that reached its apex in the 1980s was “the Pepsi Generation”. The first ad featuring the slogan was a beach scene of young people having a party. A voice fades in at the end: “Come alive, you’re in the Pepsi Generation!”

From that early ad, Pepsi expanded into more and more lifestyle ads, eventually spooking Coke into creating similar ads and even modifying the Coca-Cola formula. After widespread disapproval over the change, Pepsi became the largest beverage manufacturer in America, 0.04% ahead of Coke.

The jump in market share practically guaranteed Sculley’s ascension to the chairman position, but he was impatient.

Courted by Apple

Sculley had tried to use an Apple II in the office, but he was bewildered by the complexity of the machine, so it lay unused. Still, he was interested in high technology. As a child, he had created a color screen only weeks after Sony patented the Trinitron display.

In 1982, Sculley was contacted by a headhunter named Ed Winguth, who tried to recruit Sculley to become the next CEO of Apple Computer. Sculley was contacted by several headhunters every week and always declined.

For a while, Apple’s top pick was Don Estridge, who had headed the Chess project that resulted in the IBM PC. Despite an offer 400% higher than his salary at IBM, Estridge refused, saying that he was loyal to IBM.

Winguth also contacted Admiral Bobby Ray Inman, the former head of the NSA, who refused because he had no experience in marketing.

Acting Apple CEO and cofounder, Mike Markkula, decided that Apple was actually a consumer company and needed a CEO with experience in marketing rather than technology. A new firm was brought in, Heidrick and Struggles, which created a brand new list of candidates, with Sculley towards the top.

After the chairman of AT&T and top marketing executives at IBM turned down Heidrick’s representative, Gerry Roche, he contacted Sculley and arranged a meeting with Apple in Cupertino after Sculley returned from a sales meeting in Maui. Sculley was still not terribly interested and had intended to tell the Apple reps he was not interested.

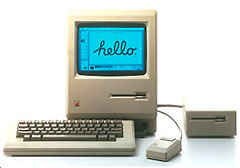

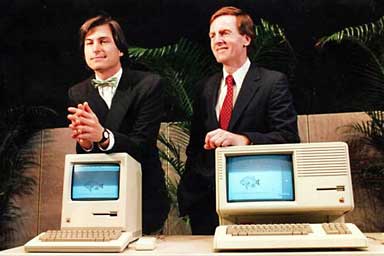

Sculley arrived in Cupertino and was surprised to be greeted by the biggest name in technology, Steve Jobs. Instead of dull talks on compensation and responsibilities, Jobs gave Sculley a tour of Apple culminating in a demonstration of the Macintosh.

Sculley arrived in Cupertino and was surprised to be greeted by the biggest name in technology, Steve Jobs. Instead of dull talks on compensation and responsibilities, Jobs gave Sculley a tour of Apple culminating in a demonstration of the Macintosh.

Sculley was floored by the interface and amused by a demonstration program that the Macintosh engineers had put together that showed Pepsi bottle caps bouncing across the screen. Impressed and intrigued, Sculley agreed to meet with Jobs in New York City for a tour of the city, since Jobs was buying a condo in Manhattan.

Jobs met Sculley in early January 1983. Markkula was itching to go back into retirement, so Jobs launched a charm offensive against Sculley. The pair toured New York, visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Central Park, and the Lincoln Center while they discussed the future of the computer industry.

Finally, Jobs invited Sculley to his penthouse condo overlooking Manhattan and famously asked him, “Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water, or do you want a chance to change the world?”

Sculley, by now infatuated with Jobs, accepted and got approval from Kendall to leave Pepsi for Apple. A few days before the Apple shareholder’s meeting on January 19, Jobs returned to New York with a cadre of Apple employees including Markkula.

After a day of demonstrations of the Lisa for reporters, Sculley took the group to dinner in the opulent Four Seasons’ Pool Room, where they discussed Apple strategy and his career at Pepsi. The evening climaxed with a monologue delivered by Sculley on how Generation X could become the “Apple Generation”.

After a day of demonstrations of the Lisa for reporters, Sculley took the group to dinner in the opulent Four Seasons’ Pool Room, where they discussed Apple strategy and his career at Pepsi. The evening climaxed with a monologue delivered by Sculley on how Generation X could become the “Apple Generation”.

Markkula approved Jobs’ choice, and they agreed upon an unheard of salary of $2.3 million (including bonuses and a housing allowance). The new appointment was approved by Apple’s board, and Markkula announced it during an executive meeting on April 8 in the Bandley 8 building. Later that day, Pepsi and Apple put out press releases announcing the change.

1983 and 1984

Sculley’s first executive meeting as CEO was on Wednesday, April 13, 1983. Many Apple veterans were put off by Sculley’s clothes even before he spoke. Most of the Apple employees dressed casually, but Sculley was decked out in a business suit and tie – unheard of except when executives had to impress outsiders.

Sculley made up for his uncharismatic appearance during his speech on how Apple would have to change to compete with IBM. He said that Apple had to maintain its entrepreneurial spirit even as the company expanded into new markets. He also wanted to diversify Apple, which was almost totally reliant on the Apple II for its revenues.

Most of the employees were thrilled with Sculley’s goals for Apple, though they were not impressed with his technical prowess. During the April 13 meeting, an engineer asked Sculley how Apple would approach connectivity. Sculley leaned over to an aid and asked, “What is connectivity?” He had a hard time understanding what the engineers were doing and started devoting a large part of his day to studying product descriptions and even engineering references so he could communicate with Apple’s moneymakers.

During his early days at Apple, Sculley mostly deferred to his senior executives and Jobs. Apple grew rapidly during 1983, despite industry pundits’ predictions that Apple II sales would peter out. Even the Apple III (see The Ill-fated Apple III and 2 Apple Failures: Apple III and Lisa) did well, with over 100,000 units sold in 1983 alone (almost three times what was sold in 1982).

Because of Sculley’s charisma, he was interviewed frequently, and with Jobs became the de facto representative of the computer industry. His relationship with Jobs also thrived; the two went out on long walks and even occasional trips to the mountains outside Cupertino for hikes.

Sculley thought that he would be able to teach Jobs the ropes and hand him the reigns of a stronger Apple after five years. During a dinner party near the Macintosh introduction, Sculley said, “Apple has one leader, Steve and me.”

Their relationship reached its zenith during the Macintosh launch. Sculley had almost no influence over the Macintosh project. Macintosh was Jobs’ fief, and he defended it fiercely (often at the expense of the Apple II). Sculley didn’t even have control over the advertising campaign, the element of the Macintosh that he was most qualified to work on. He hated the 1984 ad (along with the rest of the Apple board) and joked that the twenty page brochure included in Newsweek was actually an Apple magazine with a Newsweek insert. Despite his qualms, the two ads ran and were incredibly successful.

Their relationship reached its zenith during the Macintosh launch. Sculley had almost no influence over the Macintosh project. Macintosh was Jobs’ fief, and he defended it fiercely (often at the expense of the Apple II). Sculley didn’t even have control over the advertising campaign, the element of the Macintosh that he was most qualified to work on. He hated the 1984 ad (along with the rest of the Apple board) and joked that the twenty page brochure included in Newsweek was actually an Apple magazine with a Newsweek insert. Despite his qualms, the two ads ran and were incredibly successful.

John Sculley’s two sole contributions to the Macintosh project were the covert funding Macworld, of a Macintosh-themed magazine from IDG. The other was the Mac’s price of $2,495, which he raised from $1,500 to maintain an exorbitant 55% profit margin.

The Macintosh Launch – and Crash

Jobs’ luck was about to run out. The Macintosh had an excellent launch – and truly awful sales after that. Jobs predicted that Apple would have sold 2 million Macs by 1985, but the company only sold about 250,000. This was largely due to flawed marketing.

The Macintosh was intended for business users, but they had little use for a machine without a hard drive or a high quality printer. Consumers shied away from the machine because of its price. There was no market for the Macintosh.

What’s worse, Apple II sales had slowed dramatically. The PC compatible market was growing exponentially, but the Apple II’s growth was dropping off. It peaked at $2 billion in 1985.

Worse, there were competitors to the Macintosh emerging. Digital Research, the company that had released the first successful personal computer operating system, CP/M, was working on a Macintosh-like interface called GEM. VisiCorp, the company that created VisiCalc, released VisiOn, which was a graphical interface bundled with a full featured office suite.

The biggest threat, however, came from Microsoft and IBM with their OS/2 and Windows efforts. Apple’s board of directors insisted that Sculley “contain” Jobs to avoid other dud products and protect Apple from its growing competition.

Meanwhile, Jobs was leading the Mac team on the ill-fated Macintosh Office and the Macintosh successor, BigMac. The first portion of Macintosh Office released was the LaserWriter, a high-end, networked laser printer. Based on software from the fledgling Adobe Systems, the LaserWriter created letter quality output and could be shared by multiple machines via an AppleTalk network.

The rest of the Macintosh Office wouldn’t be launched for some time. The most important element, the intranet server, File Server, would never be released. In 1989, Apple would release AppleShare, but it took over the entire Macintosh. The product never took off.

BigMac was totally stalled. The existing Macintosh software would be replaced with Unix. Apple had gotten as far as buying a Unix license from AT&T, but development of the Macintosh environment that would run on top of Unix bogged down. After spending millions of dollars on a worthless Unix license, the project was canceled.

Ousting Jobs

Sculley, who fancied himself as Jobs’ mentor, was now forced to push him out of the company he had founded. Jobs would still have the chairman title and would still own 15% of Apple, but he would not have an assignment. His office was moved to a nearly deserted building on the Apple campus that Jobs dubbed Siberia.

Jobs was unwilling to be relegated to irrelevancy in the company he founded and started conspiring with Apple executives to seize control from Sculley. He started talking to the top executives, gauging their support. Gassée (see How Jean Louis Gassée Changed the Mac’s Direction) and Jobs never got along, so he was the last person that Jobs talked to. Gassée immediately told Sculley about Jobs’ plot while Sculley was on a visit with China’s vice-premier. Sculley canceled the trip and returned to Apple, where he called a board meeting for April 10, 1985.

Sculley was infuriated with Jobs at his act of disloyalty and stupidity. Such backstabbing never took place at Pepsi. People were fiercely competitive, but they were honest about their ambitions. Besides, Jobs knew that Sculley intended to step down in 1987, five years after he joined Apple. Sculley – who was so angry that he reverted to his childhood stutter – harangued Jobs for being dishonest.

Ultimately, Jobs challenged Sculley to allow the board to decide who would lead Apple. The body was unanimous in favor of Sculley; Jobs was forced out of Apple.

Several weeks later, presumably out of spite, Jobs released his resignation letter to the press, expecting public sympathy. Instead, Apple stock rallied. Jobs would go on, with a number of high level Apple employees, to found NeXT, a company that would create computers for higher education.

For a while, it looked like Apple would collaborate with Jobs through licensing the Macintosh software and even buying 10% of the venture. The rift was too great, and the two companies eventually sued each other (though they settled out of court).

Reorganization

Sculley now started acting on his own and implemented a much needed reorganization. Until then, Apple had been organized by product. Each division had its own marketing team and design team operating independently from the other divisions. Before Jobs left, the Macintosh and Lisa were merged into a single division, Apple SuperMicros.

The other two major divisions were the Apple II and Apple III. These divisions were almost at war with each other. The engineers would not communicate with each other, and as a result there were lots of superfluous projects. Worse than that, the marketers didn’t talk to each other, causing different projects to target the same audience (Apple III, Apple IIe, and Lisa) and actually compete with each other.

To solve this, Sculley implemented a more conventional structure based on function. All product development would take place in one division. The engineers would collaborate with marketers, who were in their own division. Then the product would be manufactured and sold in two more divisions. The heads of the divisions all reported directly to Sculley. This organization would yield Apple its biggest growth, percentage wise, in its history prior to the return of Steve Jobs in 1997.

The most important man in the executive suite was Del Yocam, the brand new COO. Yocam joined Apple in 1979 and was incredibly popular. In the early days, he brought some order to Apple’s manufacturing, making sure that there were no shortages or surpluses. He quickly became famous for carrying a green ruled notebook wherever he went to record the promises of executives.

He was fastidious in appearance and micromanaged the company to make sure supply met demand. In theory, everybody else reported to him, but he was little competition to the likes of Jean Louis Gassée and, later, Michael Spindler.

The New Team

Jean Louis Gassée was a passionate Frenchman who piloted the Apple France subsidiary of Apple Europe to greatness. In 1983, he was called back to Cupertino, where he worked on the Macintosh marketing team. While there, he helped create the European launch campaign. Many Europeans were not familiar with the novel 1984. Instead, the slogan “Il était temps qu’un capitaliste fasse une révolution” was used (“It’s time a capitalist starts a revolution”). The campaign was hugely successful and lasted for several years, much longer than the 1984 campaign did.

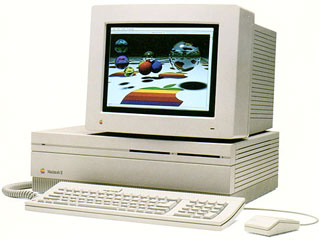

Gassée was promoted to head product development after Sculley’s big reorganization and commanded a great deal of loyalty from his employees. Sculley believed that Gassée would be able to be Apple’s new heart, a role which he enthusiastically adopted. He often said “you must bleed in six colors”, a reference to the multicolored Apple logo.

Gassée had the total respect of the engineers, because he showered them with praise and perks. It was not unusual for engineers to received $5,000 bonuses for completing projects ahead of schedule. Sometimes entire project teams would take a holiday together to Mexico – and once to Europe. The engineers were also pleased with Gassée’s hands-off management style. He had been trained in physics, but he was no engineer and usually did not become involved in projects, allowing engineers to create products without markets.

The two important sales executives were “Coach” Bill Campbell and Michael Spindler. Campbell was tapped to head Apple Americas (Apple’s US sales subsidiary) after a stint coaching college football at Stanford University. He presided over huge growth both in the Macintosh and Apple II lines and was well liked by his staff. Campbell was a very hands-on manager, often accompanying his subordinates on sales calls across the nation.

Spindler was very different from the coach. Spindler had risen through the ranks of Apple’s European subsidiary and was promoted to head Apple Europe, which covered Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. Far from hands on, Spindler was almost exclusively a strategist who delegated day to day operations to his subordinates. His strategy of being “multi-local” resonated with Sculley. Spindler customized products and promotions to fit the market, acting like a local company with the resources of Apple Computer.

Incredibly forceful, Spindler seemed apt to explode with excitement when explaining an idea. He would breath hard, speak rapidly (sometimes in an unintelligible German accent), and scrawl illegibly on white boards. Not only that, Spindler spent a great deal of time on the job. Nicknamed “the Diesel” for his work habits, Spindler often had trouble dealing with stress. On more than one occasion he had to be coaxed out from under a desk because he was so overwhelmed with stress.

Just months after Jobs departure from Apple, Spindler cemented his reputation through an impassioned speech given to every employee at the Apple campus in Cupertino. Spindler whipped the audience into a frenzy (he was always more eloquent and inspiring with Apple audiences than with outsiders) and even inspired a fashion fad on the campus. Workers created T-shirts emblazoned with a phrase from his speech: ONE APPLE.

Apollo

To make up for the death of BigMac, Apple began a devastating relationship with the struggling workstation manufacturer Apollo Computers. Apollo was wilting in the face of the powerful Sun Microsystems. The company had been the earliest successful workstation manufacturer, but in the 1980s, it had lost the title to the low cost, high volume Sun. Now Apollo was struggling for survival, and the Macintosh seemed like a sure fire way to differentiate its products from Sun’s. Apollo wanted to license the Macintosh interface for its operating system, Domain/OS (based on Unix), and would allow Apple to sell rebranded Apollo workstations to high end designers, and to enterprise.

Apollo did most of the work and was relatively successful. In a number of months, Macintosh software was running on top of Domain/OS reliably – and much faster than on the Macintosh. On top of that, existing Domain/OS applications ran, too. Apollo had devoted most of its limited resources to porting the Macintosh and was still losing ground fast to Sun.

Apple stunned the company by abruptly canceling the agreement (at the behest of Gassée). Apollo was eventually forced to the brink of bankruptcy and was acquired by HP in 1989. Gassée would go on to pioneer the creation of the Macintosh II.

Apple stunned the company by abruptly canceling the agreement (at the behest of Gassée). Apollo was eventually forced to the brink of bankruptcy and was acquired by HP in 1989. Gassée would go on to pioneer the creation of the Macintosh II.

New Focus, New Markets

With a strong and cooperative executive staff (at least for now), Sculley set about saving Apple, which was on track to post a loss for the year. That would be the first in Apple’s history. He wanted Apple to release products attractive to business users, and after the release of Aldus PageMaker in 1985, to desktop publishers in addition to Apple’s traditional SOHO (small office, home office) markets.

Sculley did more than just promote the Mac to reach the brand new markets, he also aggressively recruited developers. Jobs had created a corps of evangelists to promote the Macintosh to third party developers. The head of the program, Guy Kawasaki, was given permission (sometime after the fact) to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to bring new programs to the Macintosh. Some of their tactics were novel, like buying beta programs to run on demonstration Macs at retailers. Other times Kawasaki simply bought software or sometimes even brand new Macs for developers.

Apple’s most important developer by far was Microsoft. Bill Gates, a mere millionaire at the time, had worked closely with Jobs to develop Microsoft Word and MultiPlan in tandem with the Macintosh. Sculley desperately wanted to keep Gates from releasing the products (which received rave reviews) for DOS or Windows, so he asked for an exclusivity agreement. Gates would hold off on releasing Word or MultiPlan on other platforms for two years, but he would be able to use the same displays in those products as they had on the Macintosh. What’s more, he would be able to use Macintosh-like interface elements in future versions of Windows.

Sculley and the chief counsel didn’t even notice these clauses. They thought they were just getting a head start on the competition, but they were giving Microsoft permission to mimic the Mac on any platform Microsoft wanted to with no legal recourse. At least Apple had an agreement with Microsoft to get a very capable word processor and spreadsheet.

Evangelist efforts were enormously successful, and products like FrameMaker, Mathematica, and Quark XPress made their way to the market.

To keep attracting high end buyers who would be willing to buy products with a huge profit margin, Gassée created a bevy of expensive, powerful Macs, reasoning that users would be willing to pay to avoid DOS. As a result, with nine models available in 1989, there were no Macs that cost less than $3,000.

This trend reached its apex in 1990 (when Gassée was on his way out) with the release of the Macintosh IIfx, which would be the most expensive Macintosh ever, costing $9,870 with a monitor, keyboard, and mouse.

This strategy proved to be very effective in growing the installed base rapidly. In 1984, Apple sold fewer than 300,000 Macs. By 1989, Apple had sold over 3 million Macs. All the while, Sculley was aggressively promoting Apple in the media. He often told his executives that Yocam and Gassée were the private face of Apple, and he was the public face.

Apple was by now (after a series of serious missteps by IBM) the largest PC manufacturer in the world, so Sculley was in high demand as the spokesman for the entire industry. He was giving interviews an average of twice a month from Apple’s own TV studios on Bandley Drive.

Invisible Quagmire

Sculley’s detached style, deferring most of the management decisions to his subordinates, would prove ineffective, though the extent of Apple’s inefficiency would only become evident years after Sculley left.

The first of these missteps came when Sculley decided to spin off Apple’s software arm into a brand new company and eventually allow it to go public. Sculley wanted a company he could count on to produce Macintosh software, and he was willing to sacrifice developer relationships to accomplish that aim. Claris would be headed by Bill Campbell, the affable head of Apple Americas. The plans to take Claris public quickly fell through, and Claris became an ordinary software company (albeit on with well respected products).

Allan Loren was recruited from Cigna, where he had been the IT director for the insurance giant. Sculley named him successor to Campbell, presumably because he would be able to woo over the high volume corporate customers that Sculley so lusted after.

Loren was a terrible salesman and an uninspiring leader. One of his salesmen had taken him on a sales call to one of the most important Macintosh customers, Motorola. After they arrived, Loren launched into a tirade on how Motorola had to adapt to beat the Japanese semiconductor manufacturers. The CIO was so angry with Loren that he told the salesman that he would remove every Macintosh from Motorola if Loren ever came again.

Perhaps even worse than that, Loren was rude to subordinates. He fell asleep during presentations, and he ripped them apart when he was awake. Several times he reduced the presenter to tears. Loren was hardly qualified to run a sales force, much less the largest subsidiary at Apple.

The executive staff was in turmoil. Everybody feared the power that Yocam was amassing, thinking that he would soon succeed Sculley as CEO. At a meeting in Paris to discuss the upcoming 1989 fiscal year plan, Kevin Sullivan, VP of human resources, told Sculley that he, Gassée, Spindler, and Loren would not work with Yocam.

Windows Competition

Meanwhile, Apple was in trouble. In early 1988, Microsoft had released Windows 2.03. Unlike Windows 1, Windows 2.03 was capable of displaying overlapping windows (like the Macintosh), and was much faster. More importantly, there were now Windows versions of Microsoft Word and Excel (the successor to MultiPlan) available.

Outside developers had shied away from Windows 1, preferring GEM as a runtime environment. But now developers flocked to the platform as an easier way of creating graphical programs. The most formidable of these developers was Aldus, who released a version of PageMaker for Windows.

Sculley tried Windows 2.03, and he was impressed. He recognized that it was not nearly as good as the Macintosh, but it would be adequate for many people. Gassée was outraged by the affront of Windows 2.03. He saw that it used several interface elements that were clearly derived from the Macintosh – the menu bar was nearly identical, even down to the labels. Gassée insisted that Apple retaliate.

On March 17, 1988, Apple filed suit against Microsoft and Hewlett Packard. The Apple legal team made the case that over 189 visual displays violated Apple’s copyright for the Lisa and Macintosh.

Unfortunately, Apple had licensed the software to Microsoft in the 1985 agreement. On July 25, 1989, the judge ruled that all but 10 displays from Windows were legal under the previous agreement. Apple insisted on throwing good money after bad and filed two appeals, one to the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and one to the US Supreme Court. Both bodies rejected Apple’s appeals.

Sullivan, Gassée, Spindler, and Loren all reported to Yocam, and it drove them crazy. Loren had a type-A personality and kept meticulous records of his meetings with the executives. If they didn’t meet their claims, they would have to explain why to Yocam. The others made such a fuss that Sculley reorganized Yocam out of Apple in August 1988 by eliminating the COO position – and sealed his own fate.

Engineered by Sullivan, the very man who had spearheaded the effort to get Yocam out, the reorganization made little sense to the Apple rank and file. Gassée’s division, Apple Products, took responsibility product marketing in addition to product development. Spindler was the head of a larger Apple Europe, and Loren’s fief was renamed Apple USA.

Yocam’s role was much less clear. Yocam was assigned to a new division that combined the enormous education sales division and the Pacific sales subsidiary (covering the Pacific Rim and Australia). The combination was inexplicable. Sculley was unable to rationalize Yocam’s new position, so he had the PR people draft a glowing press release. It was no matter; Yocam resigned only a few days after his reassignment.

Apple’s employees were shocked and angered at the reorganization. The old structure had grown the installed base Macs from 500,000 to 2.25 million in only three years. Apple had become a $4 billion company, larger than Microsoft several times over. Now an outsider had created a “flatter organization – one with few layers of management – that will allow a larger Apple to become even more innovative, flexible, and locally responsive than we are today,” according to Apple’s annual report to stockholders, but really he had merely divvied up Apple into inefficient, feuding fiefs. Everything was set for a power struggle, and Sculley had allowed it to happen.

Apple was beginning to stumble publicly. Gassée was irrationally protective of his high profit margins (sometimes over 60%, double what other PC manufacturers commanded). As a result, he was dead set against any low-end Macintosh. He feared that any such product would cannibalize sales and hurt Apple Product’s budget.

Apple Products was totally out of control. Gassée did little to limit the engineers to feasible projects or even keep them to release schedules. Apple invested around $500 million a year in research but only managed to release around six new products annually. Most of the money was sunk into massive, dead-end products with huge staffs and unclear goals.

Aquarius

One such project, which had the blessing of not only Gassée but also Sculley, was named Aquarius.

As the 1980s wore on, the Macintosh had begun to lose its technical edge. The 68k line of processors had once been the architecture of choice for workstation manufacturers everywhere, but it was being superseded by custom RISC chips, like the Clipper, SPARC, and Alpha. Engineers in the Apple think tank, Advanced Technology Group, believed that Apple’s only solution was to design a microprocessor on its own.

This new project was named Aquarius, and it was totally infeasible. Apple was not a microchip company, and it didn’t have the resources to become one. It would have to hire a staff familiar with microprocessor design, buy the equipment required to implement the designs, then manufacture the final products (or hire a firm like Fujitsu or Hitachi to do so). Companies like Intel and Motorola spent billions of dollars a year designing and manufacturing microprocessors. Apple was well off, but it didn’t have billions to spend.

Sam Holland, the man who had proposed the idea in the first place, was tapped to lead the project. The other engineers at Apple were aghast, including Steve Sakoman, who had personally urged Gassée to can the project. Nonetheless, Gassée did not hesitate to lavish the project with resources. He even authorized the purchase of a $15 million Cray supercomputer.

Covering his tail, Gassée told investors that the machine was used to model Apple hardware.

Holland intended to create a four-core processor, one which would behave like four processors and allow for true multitasking. This was unprecedented in 1987, and for good reason. Four processors would generate an incredible amount of heat, and, worse, would be far more complex than a single-core processor, allowing for more mistakes.

Little progress was being made on the project, and Holland left. He was replaced by Apple Fellow, Al Alcorn. Alcorn was a legend in the industry. He had invented the Pong computer game, and hired Jobs at Atari as a technician. Alcorn, in turn, hired a true chip expert, Hugh Martin.

Sculley had by now grown weary of the money pit that Aquarius had turned into. He called a few engineers into his office to explain what progress was being made.

Marting told him the project was “ridiculous”. Apple could not possible compete with Motorola or Intel. Instead, Apple should take advantage of its strengths and capitalize on user interfaces and hardware. Sculley ignored him, though Aquarius would die anyway. In 1989, Alcorn dismantled the project, and the Cray supercomputer was given to the industrial designers to create Macintosh cases.

Newton and Looking Glass

Another ill-fated project was started in 1987. Sakoman, who had so roundly condemned the Aquarius project, was now interested in creating the successor to the Macintosh. He had worked on several dead-end projects and had made a name for himself as a competent engineer and popular leader, so Gassée had no qualms on allowing him to start a research project to research tablets. He moved to a nondescript building on Bubb Road and named the project Newton (see The Story Behind Apple’s Newton).

Gassée had a problem saying no to his engineers, and he authorized another project with much the same focus, Looking Glass. Led by Marc Porat and staffed by the legendary Andy Hertzfeld and Bill Atkinson, Looking Glass would create a line of tablets connected via a wireless network. They would be equipped with “agents”, programs that would gather information on a network and then act on it. For instance, a stockbroker might create an agent that polls the share price of a particular stock, and when it drops below a certain point, would send an email alerting the broker of the change.

It was not surprising that Gassée authorized both of these tablet projects. His boss, Sculley, was obsessed with tablets. He firmly believed that the computer of the 1990s would not be the notebook or desktop, but small tablets. He went so far as to commission two video mockups of what he called the Knowledge Navigator for almost $5 million.

The Knowledge Navigator was a color tablet the size of a standard 11″ x 17″ sheet of paper and folded in the middle like a notebook. The device would have a color touch screen, a microphone, and a camera. More impressively, it would have impeccable artificial intelligence. An onscreen agent would make appointments, order products, and create reports based on previous requests.

The device would not be possible for many decades, but Sculley was always receptive to projects that contained elements of his vision.

The TrueType Story

Sculley always believed that market share was important not only to getting more consumers, but for developer relationships as well. Gassée vehemently disagreed. He was fully confident that users and developers alike would never defect from the Macintosh because there was nothing of similar quality on the market. As a result, when manufacturing chief Debi Coleman suggested that the company produce a “secretary Macintosh”, Gassée shot her down immediately. Luckily for Apple, there were no viable alternatives to the Mac.

In 1989, Apple would outrage both its consumers and an incredibly important developer. Without PostScript, the Adobe printing language, the Macintosh would have never become a major force in desktop publishing. Apple was one of Adobe’s earliest and largest customers. Adobe’s software shipped with every Macintosh and LaserWriter sold, which allowed users to create true WYSIWYG output. PostScript defined all of the shapes, fonts, and colors in a single document in a language that allowed it to be printed very accurately and be easily manipulated.

The software was well respected and very expensive. During the development of the LaserWriter, Jobs had invested $2.5 million for a 15% stake in Adobe. On top of that significant investment (which made Apple the largest stockholder of Adobe), Adobe charged Apple $300 for the fonts that shipped with the LaserWriter in addition to the money it charged for the standard PostScript software.

Gassée was being pressed to lower prices – but not profit margins – and cutting off Adobe would be an easy way of doing it. Gassée invited the normally placid cofounder and CEO of Adobe, John Warnock, to lunch at the Good Earth Café and told him that Apple would not use Adobe’s software on low-end Macs. Instead, Apple would create its own font technology.

Warnock was outraged. He left in a huff and was almost in tears. Gassée then initiated the Royal project, which was to replace the expensive Type A Postscript fonts from Adobe that Apple spent hundreds of dollars on for every printer it sold.

Microsoft was also looking for a cheap printing technology for the upcoming Windows 3.0 and OS/2 releases. Instead of developing its own technology, Microsoft acquired Bauer Enterprises, which had created a competitor to PostScript called TrueImage. Several of Bauers’ employees had left to work with Apple on a new font technology that was named Royal, which was by now almost complete. Gassée still did not have a technology to render shapes and images on printed page, and TrueImage did not have a font technology.

Gassée was desperate to get the cheap technology into Macs and reached an agreement with Microsoft to license TrueImage and Royal. Royal was then renamed TrueType and would be used in subsequent releases of the Macintosh System and Windows.

Sculley was to be announce the agreement at the Seybold Desktop Publishing Conference in San Francisco. The program was a total surprise to Sculley, who had no idea that Gassée had made an end-run around Apple’s vital ally, Adobe – especially one with Microsoft in the middle of the look and feel case. He was incensed.

So was the mild-mannered Warnock. During his speech, he compared the new technology (which provided inferior output compared to PostScript) to snake oil. He had reason to be upset. His long time ally had caused Adobe’s stock price to drop by almost 50%. Apple’s whim had cost Adobe and its investors millions of dollars (including Apple). Apple then unloaded its shares and got a $79 million return on its investment.

For all the duress caused, Apple quickly dumped TrueType. The printers never yielded very good output and were relegated to the cheapest, lowest profit printers and computers. For almost no gain, Apple had alienated its most valuable developer. The two would eventually make up, but not before Apple got a reputation for abusing developers and had essentially given Microsoft free Apple technology.

More Gassée Mistakes

Gassée stumbled again when he allowed the system software division to split up. One group would create a stopgap version of the Mac OS, and the other would create the next generation version. The teams were named, respectively, Blue and Pink. Naturally, the engineers all flocked to the more advanced project, and Blue suffered. The heads of the Blue team, Gifford Calenda and Sheila Brady, were forced to hire engineers with no experience. Almost the entire graduating class of Dartmouth was hired to work on Blue. Both projects would miss their deadlines by several years and ate up resources from successful projects.

In 1989, Gassée and Loren made the biggest mistake of their careers and severely damaged Apple’s stellar reputation with customers. The PC market took off in a big way as IBM faltered with their proprietary PS/2 line. There was a binge of computers on the market, and that taxed the suppliers of DRAM chips. Prices soared, though Apple’s hefty profit margins could sustain the hit.

Unfortunately for Apple, Gassée and Loren had no intention of reducing profit margins and decided instead to raise prices across the board. Apple lost its opportunity to drop prices, and even worse, alienated its customers. Sales plummeted for the first time since 1984. DRAM prices eventually settled down, but Apple’s stellar reputation had been sullied.

Gassée would ultimately lose his job for the dip in demand and customer loyalty. In 1989, he was stripped of most responsibilities, and he resigned one year later to found Be Inc.

After Gassée left, another reorganization was put into effect, making Spindler the new COO. Loren was also out, replaced by the former HP executive, Bob Puette. Puette had overseen the burgeoning PC division at HP and was respected by his peers. He was not a typical Apple employee, however. He was very operations driven (like the fallen Yocam) and was a big game hunter.

QuickTime

Apple’s most important Macintosh software began development shortly after the Adobe-Microsoft tussle and DRAM catastrophe, QuickTime. Like the Newton, Macintosh, and Apple II, QuickTime was developed by a group outside of the corporate structure.

Bruce Leak recognized that the projects that were blessed by the executives were very rarely successful, like Pink or the BigMac.

Earlier video initiatives at Apple (and throughout the industry) focused on adding special hardware to the computer to allow for uncompressed videos to be played. Instead of adding special hardware, Leak would compress the video files to make them playable on even inexpensive hardware. As a result, video quality was low on most computers. If the user had a specially outfitted Mac with DSP chips, quality would increase dramatically.

Looking for a Way Out

Despite outside appearances of growth (Apple was the largest PC manufacturer by 1990), Sculley and the rest of the company knew that the growth was unsustainable. Dan Eilers, a young executive, delivered a presentation that outlined the need for a discontinuous jump in Macintosh market share to maintain Apple’s dominance position in the industry. The accompanying report presented four options for upping the market share:

- License Mac OS

- OEM to others

- Make Mac OS processor independent

- Create second brand

Gassée had been a strident opponent to harming Apple’s profit margins (and his budget), but Spindler was more pragmatic. Still, the first three options were unpalatable to Spindler and the rest of the executive suite. The fourth option, creating an independent brand was much more attractive.

Sculley even put another option on the table, finding a buyer for Apple.

Apple’s Claris subsidiary was tapped for the second brand plan. Claris would produce its own Macs based on Apple logic cards, but they would be housed in industry standard cases. Ideally, the computers would sell for around $1,000 less than the comparable Apple model, making them competitive with MS-DOS competitors.

This terrified Puette, who recognized that a cheap Macintosh would cannibalize his division. Despite Sculley’s support for the project, it was canceled.

This prompted Sculley to start looking for either a strategic partner or a buyer. The first serious option came from Novell, which had recently acquired Digital Research’s software, which included GEM. The bulk of Novell’s business came through a software package called NetWare, which allowed an ordinary PC to host an entire intranet inexpensively.

As Windows and MS-DOS became more popular, Novell began to feel the squeeze from Microsoft, which was encroaching into its territory and even discouraging OEM’s from licensing NetWare client software. Novell wanted to cut Microsoft out of the picture entirely and needed to create an entire desktop system.

Instead of reviving GEM, Novell made a proposal to Apple to license the Mac OS to run on top of ordinary PCs. Spindler happily agreed, and the Star Trek project was born (see Star Trek: Apple’s First Mac OS on Intel Project), but it was killed very soon after the team created a working prototype version of the Mac OS running on Compaqs.

It was now that Spindler really began pushing Sculley to find an outside buyer. He reasoned that with the Apple brand and a larger company’s distribution channels and cash, the Macintosh could capture 25% market share and effectively the control the industry.

The first company that contacted Apple was by far the most promising, Sun Microsystems. Sun had decimated the workstation industry with its inexpensive workstations based on the 68000 processor and was now threatening what was left of the minicomputer and mainframe business with its advanced SPARC architecture (which was based on RISC).

There had been low level talks with Sun since 1988 about merging, adopting SunOS (which was by now renamed Solaris), or even buying Sun outright. But now Sun got serious. It wanted in the desktop market, and Apple could be its ticket. Sun CEO and cofounder, Scott McNeally, proposed that Apple buy Sun at a reduced price and install him as COO. Spindler would have none of this and convinced Sculley to scrap the deal.

Then, unexpectedly, IBM CEO Jack Keuler contacted Apple and Sculley about two very different proposals. IBM wanted to partner with Apple on RISC. IBM had been working on RISC technology since the 1970s, and after releasing the dog IBM RT/PC, it had hit its stride with the POWER line of processors powering its enormously successful RS/6000 line of workstations.

IBM wanted Apple to adopt the POWER line for its high-end computers. The management was excited by the offer. There were several projects deep in the bowels of research and development to move the Macintosh to RISC, all started after the failure of Aquarius, but they had all been unsuccessful. Apple gladly accepted the offer and began work on what would become PowerPC, which would be released well after Sculley had left Apple.

Sculley asked Keuler if IBM was interested in buying Apple outright. In short, no. IBM had too much tied up with OS/2 and PC-DOS to take on the Macintosh as well. But Sculley was tipped off to start talks with AT&T. AT&T was making huge investments in personal computers. The company was installing a nationwide data network, ISDN, and was experimenting with handheld computers with GO. Negotiations had gotten as far as creating a brand new organization chart for the new company, but suddenly fell through at the behest of the AT&T board, which wanted to focus on resuscitating the struggling PC manufacturer it had bought a year before, NCR. Besides that, AT&T was already in the process of finalizing the acquisition of a cellular communications company.

Sculley was contacted by an IBM headhunter about a year later, inquiring whether Sculley was interested in becoming CEO of IBM. Sculley was very interested, and he talked with the headhunter off and on for two months, but was eventually rejected in favor of the former CEO of Proctor and Gamble. Sculley was also contacted by Kodak and AT&T, but he turned them down.

During this time, Sculley was devoting a great deal of his time to the Bill Clinton campaign. Sculley was a lifelong Republican, but he felt that Clinton had the only sensible approach to technology. His name was floated as a possible running mate, but he was eventually offered to be Deputy Secretary of Commerce. He refused, but Sculley was still invited to Clinton’s first Stat of the Union, where he sat next to Hillary Clinton.

This was the last straw for the board, which was incensed that Sculley was devoting so little attention to the company as chances for a discontinuous jump slipped away. Sculley exasperated matters by telling the board that he wanted out as early as 1990 and even told them that he was interviewing with IBM.

Ouster

The board had tolerated Sculley because he had consistently delivered on his predictions, but his luck was about to run out.

Sculley had assured the board that Apple would continue growing. The company’s stock price had neared $70 in the middle of 1992, but it was in sharp decline. By the first quarter of 1993, Apple had posted a profit of $4.6 million, a fraction of what the company had earned the year before. The stock lost almost two-thirds of its value in just a few weeks.

Before the market heard about the disappointing quarterly results, the board was notified during a board meeting held in Apple headquarters on June 17, 1993. Sculley explained that the drop would be temporary, but the board was not buying it.

For years (ever since Gassée had been forced out), Spindler had been groomed as Sculley’s successor, and he was salivating at the chance of replacing his former mentor. After Sculley’s presentation, he was asked to leave the room and then elected to replace Sculley. Sculley was called into the boardroom, and left minutes later, visibly shaken.

After Sculley left, Spindler claimed he was given 15 minutes to decide whether to take the job, but it was a lie. He had been instrumental in removing Sculley from Apple.

After Apple

Sculley stayed on long enough to preside over the moderately successful Newton introduction. He took the CEO job at Spectrum while the company was in the middle of a class action lawsuit for defrauding stockholders. The company went bankrupt, and Sculley went on to head Kodak’s digital camera division until 1995, when he confounded Sculley Brothers LLC, a venture capitalist firm.

Further Reading

- The Ill-fated Apple III

- Macintosh Prehistory: The Apple III and Lisa Era

- How Jean Louis Gassée Changed the Mac’s Direction

- The Story Behind Apple’s Newton

- Star Trek: Apple’s First Mac OS on Intel Project

Bibliography

Some of the sources used in writing this article:

- Apple: The Inside Story of Intrigue, Egomania, and Business Blunders, Jim Carlton

- Infinite Loop, Michael Malone

- The Second Coming of Steve Jobs, Alan Deutschman

- Apple Confidential 2.0, Owen Linzmayer

- Odyssey: Pepsi to Apple . . . a Journey of Adventure, Ideas & the Future, John Sculley

- Wikipedia

Keywords: #johnsculley

Short link: http://goo.gl/xrFrxb

searchword: johnsculley