Michael Spindler was born during the last throes of Nazi Germany. The family was split up before Spindler was born, because his father was forced to work at a munitions plant. The absence of his father during his early childhood appeared to make Spindler even more motivated to prove himself. He excelled in school and graduated from the prestigious Rheinische Fachhochschule with a degree in engineering in 1964.

After university, Spindler found work at the Paris-based European subsidiary of DEC, which was riding the minicomputer wave of the late 60s and early 70s. Despite his engineering background, he worked in marketing, crafting strategies to get the DEC minicomputer into European offices where IBM still reigned.

It was at DEC where Spindler gained a reputation for his work ethic. He kept long hours and was huge (over 6′ tall), which earned him the nickname “Diesel”. The rigid corporate structure of DEC quickly tired him, and Spindler found work at the nascent Intel, where he worked in the European sales office.

Spindler made his second most important friend during his tenure at Intel, Mike Markkula. Markkula was deeply enamored with Spindler. In later interviews, Markkula described Spindler as “one of the smartest guys I know.”

Markkula became very wealthy and retired from Intel. In 1976, he became a cofounder of Apple Computer by bankrolling Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. As Apple expanded into foreign markets in 1980, Markkula recruited Spindler to help run Apple Europe’s marketing department.

Apple Europe

Apple Europe ran out of a cramped office in Brussels and had only a few employees. Spindler had never worked at the startup before, but he liked it a lot. He had freedom to try almost anything he wanted.

There were problems with working for such a young company, though. Spindler went without payment for almost six months because Apple didn’t know how to move funds from California to Belgium.

In 1981, Apple Europe moved to bigger offices in Paris, and Spindler’s career at Apple really began to take off. Apple successfully competed with native European companies like Amstrad, Acorn, and Olivetti to establish the Apple II as a major standard despite its higher price (several hundred dollars more than a comparable Acorn BBC Micro) and inability to handle non-Roman alphabets without special hardware hacks.

Spindler’s accomplishments in marketing were recognized by Apple’s new CEO, John Sculley, in 1983, he was promoted to executive vice president of marketing. Spindler now reported to Del Yocam directly and spent a couple days in Cupertino every month.

In his new role, Spindler began to show signs of debilitating stress. During his time in Cupertino, he checked himself into Stanford Medical Center several times, complaining about heart palpitations. One of his assistants once found him passed out on his couch in his office. More often, he would simply crawl under his desk until he was able to relax.

These were not behaviors to be expected from a successful executive, much less a future CEO.

Spindler had a great reputation with Sculley. Unlike the other highly political executives, Spindler seemed to pose little threat to Sculley. On top of that, he was a brilliant strategist, which won him attention both inside Apple and in the outside world.

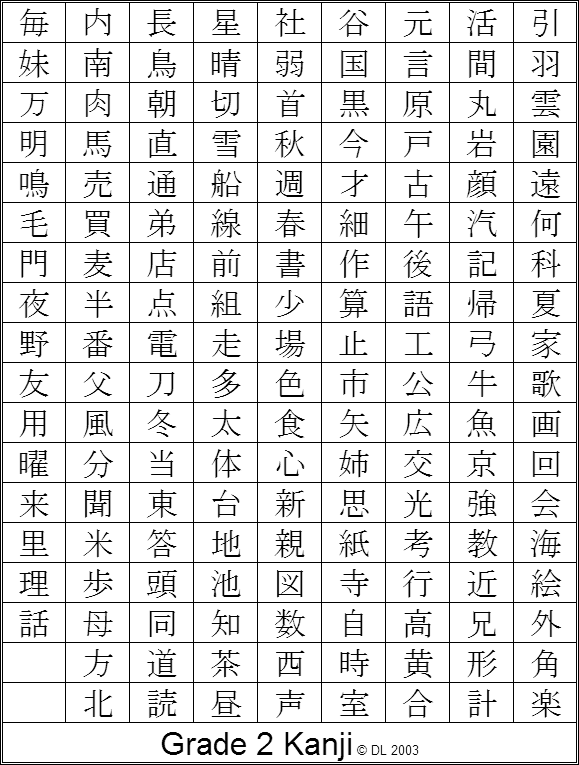

Sculley was very impressed with Spindler’s multi-localism strategy. He had Apple’s international subsidiaries run independently of the main company, releasing specialized products and advertising campaigns in every country – but unlike local companies, the subsidiaries still had the clout and influence of Apple Computer. The theory was brilliant, and it won Apple significant market share gains in Asia and Europe, where MS-DOS was unable to recognize their alphabets (this was especially true with Kanji).

Spindler was an excellent strategist, but he was no manager. He relied on his coterie of staffers to actually develop his strategies into concrete plans. They often had to do this behind his back because of the way he carried himself during meetings. He would become flustered and agitated as he spoke, and would write illegibly on the board. After he was done, he would dismiss the meeting without even asking for questions. This was a far cry from the consensus culture developing in Cupertino. This sometimes caused problems when he spoke with outsiders. He once landed a front page interview with the prestigious PCWeek, but the author was unable to understand a word of what he said. Even after a second interview, his speech was unintelligible because he was so worked up. The story never ran.

Rising Through the Ranks

In the aftermath of Steve Jobs’ departure from Apple, Sculley made his reputation as a turn-around artist. Sculley scrapped the former, product-based structure at Apple that had caused so much infighting (Macintosh vs. Lisa, Apple III vs. everyone) with a more conventional function-based structure. Research and development, manufacturing, marketing, and sales all had their own divisions, and all of the executives reported to the highly capable COO, Del Yocam.

During Sculley’s presentation of the restructuring plan to Apple employees at the De Anza Community College Auditorium, Spindler delivered an impassioned speech that won him the respect of Apple employees around the world and set the tone for the year. Titled “The Two Hearts”, the speech hit its climax with the lines “Apple beats with two hearts – our California heart and the heart of the local company.”

Spindler sounded like a southern revivalist preacher who came from Bavaria. Apple employees began wearing shirts emblazoned with the line ONE APPLE, a phrase Spindler had used in his speech.

The restructuring plan worked, and Apple began growing again, especially in Europe. Spindler was promoted to run Apple’s worldwide marketing, helping engineer the Macintosh II and Apple IIc launch in dozens of countries around the world. He was now a member of the small team of executives that essentially ran the company while Sculley acted as a glorified Apple spokesman.

Jean Louis Gassée was by far the most political of the executives. He also came from Apple Europe, where he had worked in marketing under Spindler. In 1983, he was moved to the Macintosh division, where he helped craft the launch campaign for non-English countries titled “Il etait temps qu’un capitaliste fasse une rèvolution,” (“It’s time a capitalist start a revolution.”), because of the limited popularity of Orwell’s 1984 amongst non-English speakers.

After Jobs’ departure, Gassée was promoted to run the new research and development division, called Apple Products. Sculley hoped that Gassée would become the new soul of Apple, and he did.

Gassée had a colorful personality. He often wore leather pants and a jacket, in stark contrast to many of the employees who showed up in shorts and a T-shirt. Gassée also peppered his speech with sexual analogies (many of them picked up during his waitering stint in a French men’s club).

In addition to all his color and charm, he was stubborn and power hungry. If someone outside Apple Products had the gall to disagree with him, Gassée would yell and scream until he had his way. But inside Apple Products, Gassée was immensely popular. Though he had a degree in physics, Gassée was no engineer. He rarely ever challenged project managers if they didn’t meet schedule, and there was almost no restraint to keep engineers from working on infeasible projects.

The other important man in the executive suite was Del Yocam, a plain Methodist who had signed on with Apple in 1979 and cleaned up operations. Before, parts were littered through Apple’s Bandley Drive offices, and manufacturing was handled by several contractors of varying degrees of quality (and a few outright sweatshops). This made it difficult for Apple to meet demand, much less expand and invest in research.

Yocam brought a sense of discipline to the company. Every manager became accountable. Yocam went to meetings and recorded the manager’s demand predictions in a green engineer’s notebook, and if that goal was not met, the manager was held accountable. This attitude was unpopular amongst the executives, but most Apple employees were enamored with Yocam’s straightforward personality.

In the 1985 restructuring, Yocam was promoted to COO, which put him in control of the entire company.

Spindler was well suited to run marketing. He created long term strategies, then allowed his assistants to spell out specific targets for his executives to meet. Often times, he would hold an unintelligible meeting and walk out without taking questions, then allow his assistants to move in and explain what he had said.

Spindler’s biggest triumph while he headed Apple Europe was KanjiTalk, which gave the Mac a full Japanese interface, and the explosive growth of the Macintosh in Japan. The Japanese had been slow to adopt the personal computer because of their inability to work with Japanese characters (called Kanji). Users had to type using the Latin alphabet, spelling words phonetically and losing meaning with confusing homonyms.

Spindler recognized that the Macintosh would be more than capable enough to display and process Kanji characters. Spindler had Apple Japan buy rights to a Kanji font system and implement it on the Mac 512K. The fonts were supplemented with a sophisticated entry system that used word prediction to guess the meaning of words and change Latin spellings into true Kanji. The software was called KanjiTalk, and it made Apple one of only two computer companies selling Kanji-aware computers in Japan.

The more clout Spindler gained, the more difficulty he had dealing with stress – and the more personal attacks he made about Sculley. Famously, during a tour of the Apple campus for the new head of Apple USA (Apple’s US sales division), Allan Loren, Spindler could not be found in his office. A few minutes later, Spindler walked out and introduced himself. He had either been under his desk or in his closet, the two places that were not visible through the glass wall covering one side of his office.

Sculley sometimes caught wind of Spindler’s attacks, but Spindler always denied them. In Sculley’s world, people did not lie, so he accepted these denials.

Those attacks found an eager audience with a new member of the executive suite, Kevin Sullivan, the straight laced human resources director. Sullivan seemed to have no ambition outside of self preservation and was a natural ally of Spindler. Spindler would march into Sullivan’s office in a rage about some slight, and Sullivan would pace around with him and listen to him vent. Many speculate that Sullivan decided that Spindler was the only executive inside Apple who had the momentum to be CEO (he had become a vice president in less than four years).

Spindler became all the more ambitious after a series of major missteps on the part of Gassée.

Reorganization

Apple’s fortunes were much improved in 1988, and the executives were clamoring for more power and the elimination of Yocam as COO. Yocam held people like Gassée and the brand new Apple USA head, Allen Loren, accountable, and they didn’t appreciate it. Sculley, always the hands off manager, wanted nothing more than to placate the executives and continue to promote Apple in the media (he was finishing his autobiography and beginning a book tour that would include a famous Playboy interview), so he approved a reorganization plan to flatten Apple’s structure and eliminate Yocam as a threat.

Just like Jobs in 1985, Yocam was exiled to his own Siberia, the brand new Apple Pacific and Education division, an inexplicable combination. Unsurprisingly, Yocam handed in his resignation not soon afterwards.

Spindler was given a promotion in the reorganization; he was named head of Apple Europe, an odd choice. Marketing is heavily dependent on strategies, but running an organization takes more than strategies and intelligence. It takes people skills and the ability to delegate tasks. Spindler was lacking in these qualities, but his staff shored him up. After every meeting, memo or announcement, his assistant would gather his managers together, then give them specific tasks and goals to meet. Despite questionable management skills, Spindler maintained an excellent reputation with Sculley and the rest of the company.

Gassée did very poorly with the extra power. He now had all the resources he wanted, but none of Yocam’s oversight. He was able to pursue his fanatical devotion to fat profit margins, and funnel those returns into doomed research projects like Pink or Aquarius.

Gassée Stumbles

Aquarius had begun about a year earlier as a research project to create a brand new microprocessor for the Mac. It was to be a four core RISC design, unprecedented in even the most powerful workstations from Sun and IBM.

The project was a ridiculous endeavor for Apple. Intel, Motorola, and IBM invested billions of dollars into new chip designs; Apple didn’t have that kind of money.

The necessity of a new design was also questionable. Motorola had an advanced RISC processor in the works already, the 88000, and there were a multitude of alternatives already on the market, like MIPS, SPARC, Clipper, and POWER.

Nonetheless, Gassée invested millions of dollars into the project, which employed the incredible Hugh Martin, even buying a Cray supercomputer. Gassée did not want investors to know about his folly, so he told them the Cray was being used to design brand new cases and components.

After more than $50 million, Aquarius was canceled, but Gassée did not learn his lesson. Almost no research projects turned into real products, and those that did were sold at such high prices that businesses were skittish about buying them. Macs were priced $1,0000-$2,000 above comparable PCs (Apple’s profit margins were almost double the average), but Gassée defended the prices. The Macintosh software was such a huge advantage that consumers were willing to pay a premium to use it.

At the moment, that was true, but other companies were developing viable alternatives to the Macintosh, and even before then, the user base could be alienated through foolish price hikes and shortages.

In 1989, the PC industry was taking off, and shipping volumes were increasing exponentially. There were component shortages from CRTs to keyboard interfaces. These shortages hit Apple harder than most, since it used specialized components on the Macintosh. The price hike especially affected DRAM, memory chips as cache for graphics cards on high-end Macs.

Gassée was unwilling to compromise his 55% profit margins and raised prices on high-end Macs by almost 29%.

There was an immediate backlash against Apple, and the head of Apple USA, Loren, was forced to lower prices dramatically, cutting the profit margin to 29%, the lowest in Apple history. The move ruined the chances of Gassée or Loren ascending to the office of CEO – and made Spindler the rising star at Apple.

Spindler Shines

All while the US business was sputtering, Apple Europe was firing on all cylinders. After he was given control of the division, Spindler standardized prices across the region while giving a great deal of liberty to individual countries to modify the products and marketing campaigns. It was multi-localism at work.

Sales grew from $400 million to $1.2 billion in two years. Apple Europe accounted for almost a quarter of Apple’s revenues.

After the disastrous price hike, Sculley realized that the executives could not govern themselves, so a COO would be necessary. He tried to recruit Yocam but was rebuffed, so he turned to Spindler.

Elevation

Spindler was a bad choice. The COO would be responsible for coordinating divisions, making sure projections were accurate, and managing the prima donnas like Gassée. Spindler was still just a strategist.

Sculley was marginally in control, so it’s not surprising that he would select somebody so ill-suited for the position. Others warned him not to select Spindler: Joe Graziano (Apple’s well compensated CFO) insisted that Spindler was not cut out for operations. Sculley ignored him and met with Spindler on 1990.01.30 (six years to the day before he would be forced to resign).

The meeting was held in a dumpy hotel outside JFK Airport in New York City, halfway between Cupertino and Paris. Sculley had a press release made up, and Spindler left his beloved Paris for a large house in Atherton.

Spindler’s elevation had two immediate effects. First, the head of Apple USA, Allan Loren, resigned. Loren was incredibly unpopular with his employees and with customers. The other was a power shift that forced Gassée into own his Siberia – and eventually out of the company altogether.

Gassée was mortally wounded after the DRAM incident. Before, he was the heir apparent to John Sculley (and before Gassée, Jobs had been heir apparent), but he no longer had any leverage to fight off challenges. By most accounts, he was unsuccessful. The R&D budget ballooned to $300 million, but most of the long term projects never materialized, or if they did, they were compromised, like Aquarius and the Macintosh Portable.

At the same time, he blocked any attempts at creating a low cost Macintosh intended for students or secretaries. As a result, a budget minded customer had to shell out $1,500 more for a Macintosh than a PC, even if they only wanted a word processor.

Before the first week of February was over, Graziano and Spindler were both recommending to Sculley that Gassée be fired. Sculley didn’t have the heart to push him out (or pay severance) and offered to move Gassée to Europe. Gassée responded by telling Sculley to fire him if Sculley didn’t trust him.

Gassée didn’t quit and wasn’t fired; instead, he was stripped of product development and marketing. He was left only with the long term projects that had little bearing on Apple’s business. Everybody knew that he had been emasculated, and he quit a few days later.

In protest, 150 engineers marched outside Apple’s executive building, De Anza 7, with signs of support for Gassée. Spindler never received such a reception.

The Windows Threat

Apple had a terrible 1990. Windows 3.0 was released to the world, Apple’s new version of the Mac OS, System 7, staggered to the marketplace and sales slowed markedly.

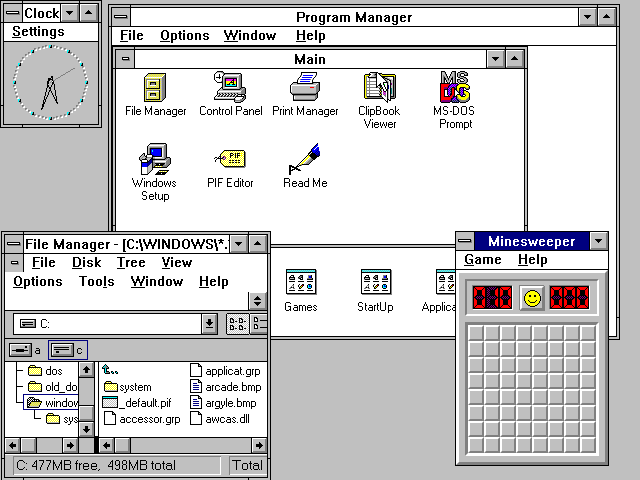

The most important event of the year for the computer industry was the release of Windows 3.0. Windows was now a viable alternative to the Mac, even if it had an inconsistent interface and was fairly unstable.

Unlike Windows 3.0, which made its debut at the posh City Center, System 7 was released at the De Anza Community College auditorium, where the Macintosh had been released six years earlier. Despite the imminent threat of Windows, the engineers in attendance were ebullient. There were a series of demos pitting Windows 3.0 and System 7, and the engineers all laughed at the inconsistencies in the Windows interface – but they failed to recognize the threat.

Windows was not as good as Macintosh,

but it was good enough for the average user.

Windows was not as good as Macintosh, but it was good enough for the average user.

Fortunately, Sculley stepped forward, just as he had in 1985, and took control of the company.

The most important thing to Apple’s future was bolstering Apple’s market share to attract new developers and users. At the beginning of 1990, Apple’s market share was at around 7.5%, and Sculley set an aggressive goal of 10%. Sculley contributed to the effort by cutting costs. The company would not buy its top 100 executives Mercedes and BMWs, and employees would be considered for raises every 12 months instead of every 6.

The task of building the market share fell to Spindler. Unbelievably, Gassée released one machine for $1,000 over the five years he was in control (the Apple IIc), and it was developed before he arrived in the US. Spindler rushed several nascent projects to the marketplace to give customers inexpensive Macs, and he created two brand new labels for consumer Macs and midrange business computers.

The business label, Centris, because it was differentiated from Quadras, but the consumer label, Performa, was the longest lived mark prior to the Power Macintosh introduced in 2001.

The Performas were rebranded versions of Apple’s low-end and midrange Macs bundled with tons of games, utilities, and productivity software packages. The Performas made Macs price competitive with PCs again and were immensely popular.

Spindler rallied the troops with a second impassioned speech delivered to Apple employees at the De Anza Community College Auditorium. He declared, “There will be no more prima donnas at Apple.” This scared some employees into line, but the line would become a punch line by Sculley’s assumption of the CTO title only months later.

This placed Sculley, a lifelong executive, in charge of Apple’s money making engineers. It was considered a slap in the face. It also showed that Sculley was beginning to regret all the power he had given Spindler.

Tremblings

Product development continued its decline under the direct control of Spindler and Sculley. Sculley attempted to hold managers accountable by meeting with them daily, but he was undercut by his lack of engineering expertise. Spindler fared no better. Projects like Pink and Jaguar, a project to create a Macintosh RISC workstation, would not succeed regardless of their budget or schedule because they were too broad and ambitious.

By 1991, the research and development budget had swollen to $600 million, and Spindler was basically powerless to cut projects as long as Sculley was CTO and a die hard advocate of the very projects that needed to be cut.

Spindler began to pack the executive suite with his supporters and implemented a doomed product strategy. Bob Puette, formerly of HP’s PC division, was tapped to head Apple USA. Puette proved disastrous for Apple’s dealer relations, but he helped accelerate sales. The most important addition to the Apple fold was Ian Diery, who headed Apple Pacific, which covered Australia, Oceania, Indonesia, and Philippines.

When Puette came to Apple, the Apple dealer network was the largest in its history, even today. There were hundreds of shops across the nation selling Macs, Apple IIs, and accessories.

This was good for consumers, who probably lived within an hour’s drive of Mac dealer, but it was bad for Apple. Its sales people had to maintain hundreds of contacts and cut deals with small dealers that were marginally profitable.

Puette’s first act was to cancel the dealer license with any company doing less than $500,000 of business a year. This was not so unreasonable a cut, but the way he implemented it would bode poorly for Apple in the future. He had his sales reps tell the doomed shops’ competitors before the shop itself. Supposedly, it was to allow for a smooth transition, but it alienated almost everyone involved.

Puette went even further. During the annual sales conference held for dealers, he announced that 20% of the dealers did 80% of the business, and any dealer not falling into that 20% that did not offer good value would be eliminated. This terrified the dealers, many of whom had stuck with Apple during the bad times after Jobs’ departure. Beyond the compromised dealer relations, Puette continued to push for artificially high profit margins, despite Sculley’s initiative to raise the Mac’s market share by 3%.

Spindler’s favorite executive was Ian Diery, the Australian amateur Rugby player. He was a manager in the Yocam mold. He held his staff accountable for their promises and projections. He didn’t hesitate to dress down those who failed to meet his expectations.

It was Diery who managed to price the Mac Classic at $999, a price that put it well below most clones of the time. Puette put up a fight, but he was unable to face both Spindler and Sculley.

With his new found support from Spindler and Sculley, Diery began acting as the de facto COO for Spindler. He assumed the same position that Spindler’s assistants did at Apple Europe. After a meeting, he would delegate tasks out to each of the managers and then check up on them to make sure the new strategy was implemented and succeeding.

For his efforts, Diery was promoted to become the executive vice president of worldwide sales, controlling not only the foreign subsidiaries, but Apple USA, which still accounted for 25% of Apple’s revenues.

Eventually, Spindler promoted Diery to executive vice president and delegated most of his day-to-day duties to Diery. To the outside world, it appeared that Spindler was still in control, but he was becoming more and more isolated and impotent.

Merger?

Despite the bevy of relatively inexpensive Macs, Apple’s future did not improve. Apple achieved double digit growth for the first time in two years, but this was well behind Compaq’s triple digit growth during the same period. Apple would not be able to achieve its market share goals and would start losing developers and customers to Windows 3.0.

With Spindler’s blessing, Sculley began the hunt for a merger candidate – but Spindler’s ego would get in the way of any deal being finalized.

Sun Micro

Sculley had considered buying Sun and Apollo in the mid 80s but decided against it at the last minute. Now Hugh Martin, a senior engineer on the Aquarius who worked on the Jaguar project, asked that the company consider merging with Sun. The company had everything Apple needed: corporate customers, a modern operating system, and a fully developed RISC architecture. Al Eisenstat, Apple’s senior VP, and Joe Graziano, the CFO who returned to Apple from Sun, both supported the deal. So did two Sun cofounders, Scott McNealy and Bill Joy.

The two companies had reached a tentative agreement where Apple would buy Sun outright. Sculley would remain CEO, and McNealy would become the new company’s COO, replacing Spindler. Graziano had a draft press release created announcing the merger, but at the last minute, Jack Kuehler, president of IBM’s PC division, called Spindler and asked about partnering up on RISC.

IBM

The call was not a total surprise to Spindler. He had called IBM a few months before touting Pink. IBM wasn’t interested, but Kuehler remembered the exchange when he and a team of IBM executives were discussing possible customers for IBM’s brand new RISC processors, called POWER.

After eliminating most of the dominant PC and minicomputer manufacturers because of conflicts of interest (most big companies already were working on RISC or were allied with Microsoft), the team thought of Apple. It was well known in the computer industry that Apple was pursuing a number of RISC-based projects, so Kuehler called Spindler to propose using the POWER architecture at Apple.

Spindler was not receptive in the least to the proposal from Sun. His position would be eliminated in the new Apple, and his hopes of becoming CEO would probably be dashed. An IBM alliance at least meant that he would be able to keep his job.

Sculley was also interested. IBM was the largest company in the computer industry and one of the largest companies in the world. IBM had the money to make major investments in Macintosh. On top of that, it had the leverage in the corporate world that would be necessary if the Macintosh was going to become the dominant PC.

Apple’s engineers did not feel so strongly though. POWER was much older than MIPS or SPARC and considered technically inferior. On top of that, IBM was Apple’s largest competitor in the PC market.

Spindler brushed the criticism aside, and pushed for an IBM alliance.

Kuehler arranged a meeting between Spindler, Sculley, Martin, and his staff at a hotel near the Dallas-Fort Worth airport. The group of executives discussed possible collaboration on Pink and porting the Mac OS to run on IBM workstations. There was too much to discuss in one meeting, so they continued meeting off and on for the next couple weeks.

One of the earliest stipulations that Spindler put forward was avoiding making Apple dependent on IBM, a competitor, for all of its microprocessors. As a result, Motorola was brought in as a manufacturing partner for IBM. After giving the Apple delegation tours of IBM’s chip manufacturing plants and discussing future software strategy, it appeared that some sort of Apple-IBM-Motorola alliance would form.

There would be three collaborations. First, IBM would adapt Motorola’s 88000 bus to the POWER architecture so that Apple wouldn’t need to scrap all of its existing design work. Second, IBM would help fund an Apple spin-off called Kaleida, which would capitalize on the burgeoning multimedia CD-ROM industry. Third, IBM would fund Taligent, an Apple spin off of the Pink project. When Taligent finished development, IBM would adopt the operating system on all of its PowerPC workstations.

The final decision was made in June 1991, and Spindler started working with Apple’s legal and PR departments to finalize the deal and publicize the two new ventures and PowerPC. The contracts were signed and the deal announced during the July 4 break on Wednesday, July 3. The specifics were announced three months later in October at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco.

Sculley, IBM CEO Jon Akers, and Motorola CEO George Fisher were all media darlings. Their faces were on the front page of USA Today’s Business section, Business Week, and almost every computer magazine in the world. The alliance between the three companies was dubbed AIM (for Apple IBM Motorola).

PowerPC

Before 1992, there were several different RISC projects at Apple. From the earliest experiments with Aquarius in 1987 to the Jaguar and Apollo workstation in 1988. In 1992, all of those projects were killed, and the new PowerPC project was born. Hardware development took place outside Apple at a nondescript office building in Austin, Texas, called Somerset. Software development took place in the AppleSoft division; it was chaotic and incredibly effective.

Development began on PowerPC even before the deal was announced by Sculley. The Apple project for PowerPC based Macs was code named Hurricane, though it was quickly renamed to Tesseract, which is a four dimensional object. The group belonged to the advanced think tank, Advanced Technologies Group, that was once head by Larry Tesler and Dave Nagel, and it was prone to bending to the whims of a few engineers (which is how Newton and Pink were born).

Tesseract was a high-end workstation for graphic designers that would cost almost $4,500. Development went slowly, since Apple opted not to use the IBM CHRP platform, so the engineers had to create the Macintosh hardware. This also meant redesigning the large ROMs that stored most of the Mac OS, like graphics routines and common file operations. Luckily, the PowerPC was going to be pin compatible with the Motorola 88000 RISC processor, allowing engineers to recycle much of the Jaguar project.

As usual, a conflict erupted amongst the engineers. Remembering Sculley’s push for low-end Macs in 1990, a group of engineers split off Tesseract to create midrange and low-end PowerPC desktops, both of which proved to be much more popular than the Tesseract. The two products (being developed by a single team) were given the code names Carl Sagan and Piltdown Man, or PDM.

Carl Sagan took exception to his name being used without his permission (Apple engineers speculated that he did not understand that the code name would not be used for the final product) and sued Apple. After a settlement, the engineers changed the name to BHA, which stood for Butt-Head Astronomer. Sagan threatened Apple again, and the product was renamed for the last time LAW, which stood for Lawyers Are Wimps.

Development went much faster on the less complex PDM and LAW. They didn’t require the multimedia accelerators (called DSPs, digital signal processors), nor did they require the large cooling system required to keep the high-end hard drive and processor cool.

All of the models were still based on the NuBus standard, a standard that new and unproven in 1988 when it was selected for the Macintosh II – and it had never penetrated the broader PC market. Fortunately for Apple, NuBus would allow most existing add-on cards to work with the brand new Macs, which was especially important to the Tesseract team.

Software development was a lot more onerous. System software development at Apple had been incredibly inefficient up until the late 90s. Apple invested hundreds of millions of dollars in Pink and Copland, but all it got in return were text encoding software used in Mac OS 8 and a nanokernel used in Mac OS 8.6.

Phillip Koch, the computer science professor who was tapped to get the Mac OS onto the PowerPC, concluded that a total rewrite would not possibly be ready by 1994. Instead, he decided to rewrite only a small portion of the Mac OS to run natively on the PowerPC and emulate the rest in software. He used the software principle that a user only uses 10% of an application’s code 90% of the time and decided to rewrite only the portions that would make the biggest performance difference. For example, the Chooser never ran PowerPC native, but QuickDraw was native almost from the start.

The project was named Psychic TV, and, like most successful Apple projects, was kept very small. His team was dominated by quirky developers who would devote hours to making a single portion of code run more elegantly. They were in the cast of people like Steve Wozniak and Andy Hertzfeld. By the summer of 1992, most of the grunt work was finished with Psychic TV. The engineers had created a piece of software that allowed PowerPC native and nonnative code to mingle unhampered by incompatibility.

For all the breakthroughs being made with the software, hardware was struggling. The Tesseract team was having trouble making the system meet their goal of $4,500. The team was not ready for the first public demonstration (which was lead by CEO John Sculley) on 1992.08.24, so the PDM and LAW team became the leaders of the RISC effort, and Tesseract was relegated to the back burner.

It was an amazing technical feat that existing Macintosh software was able to run at all after only several months of work. Despite the technical victory, Spindler was still not particularly interested, especially after he took control of Apple in summer 1993. His rare visits to the LAW and PDM projects demonstrated his own disinterest and failure to understand the importance of the projects to Apple’s future.

Psychic TV’s key developer, Gary Davidian, remembered that Spindler always seemed like he was on the verge of falling asleep during demonstrations and often asked impertinent questions. During one demonstration, Spindler launched into a monologue on how enterprise might be able to save Apple. It was clear that PDM and LAW were vital to the future, and they had to finish without the support of the COO.

While work on the Mac OS and hardware were moving along nicely, the software tools developers would use to create programs for the brand new computer were not close to being ready. The tools had been an afterthought, and Apple had contracted development out to Symantec, which owned the popular Think C developing environment for the Mac. Unfortunately for Apple, Symantec was not terribly interested in developing Mac software. The bulk of its income came from its suite of software utilities for Windows and DOS. After about a year of waiting, it became clear that the tools would not be ready.

Fortunately for the large developers, the systems that Apple was using for software development could be bought, but they cost well over $10,000. They were top of the line RS/6000 workstations from IBM that used a POWER chip, the predecessor to PowerPC. This was not an option for small developers, many of whose livelihoods depended on the Macintosh.

This grew more important as the deadline of March 24, 1994 drew near. Luckily for Apple, the Symantec agreement fell apart and the tools were never delivered. Instead, a small Canadian company called Metrowerks created a PowerPC compatible development suite called CodeWarrior. Better than that, CodeWarrior was actually faster than the prototypes of the Symantec product – and even the RS/6000 suite. As a result, even the large developers switched to CodeWarrior.

Sculley’s Departure

The announcement at the Fairmont Hotel was the high point of Sculley’s career. From there, he became less and less involved with the company. Kaleida and Taligent both failed because Sculley failed to push the Apple contingent into finishing what they started.

The Newton, once Sculley’s pet project, became less and less impressive as features had to be cut to keep the project on time and under budget. Sculley began spending more and more time supervising the project, and kept track of every success and setback.

It was now the case that the projects that received the most attention from American Apple executives were the ones doomed to fail. The three big successful projects of 1991 and 1992 were the PowerBook, QuickTime, and Macintosh Classic.

The PowerBook was run as a skunkworks project – even Spindler only dimly knew what they were working on. QuickTime found its champion in Ian Diery’s marketing lieutenant, Satjiv Cahill, who defended the project against Spindler and Sculley, who wanted to make video the domain of only high-end Macs.

Apple’s other big product was the Macintosh Classic, Apple’s least expensive Macintosh ever (until the release of the slot loading iMacs in 1999); it sold for $999. The Classic would have cost a full $1,000 more if Puette had his way, but Diery stepped forward and put up a fight.

Apple’s board of directors were not ignorant of Sculley’s impotence inside the company. He was always the public face of the company, while he delegated day to day operations to Steve Jobs, Gassée, Spindler, and whatever other executive had his favor at the time. Sculley only took control when the company was in crisis, and his solution was usually new blood rather than overarching strategies (except for his 10% goal).

The last straw came when Sculley started campaigning for Bill Clinton. Sculley had been a lifelong Republican, but Clinton’s staff and policy showed a grasp on technology (though Clinton didn’t; he sent only several emails out of the millions his administration’s staff sent, in marked contrast to George Bush and Dan Quayle).

Sculley traveled the nation, making stump speeches on Clinton’s technology. When Clinton won the Democratic nomination and eventually the presidency, Sculley was poised to be appointed Secretary of Labor (supposedly his name was floated as a possible running mate), but he was passed over in favor of Robert Reich. For his efforts, Sculley was invited to sit next to Hillary Clinton during Clinton’s first State of the Union.

In early 1993, Sculley announced to the board that he was considering going back to the East Coast and becoming CEO of IBM. The board had little patience for Sculley’s distractions, especially in the face of dire financial results.

Sculley’s emphasis on low profit margins and growing market share took its toll on earnings and profit. Despite skyrocketing sales, the company only grew by 6%, compared to 15% during the previous quarter. Net income told a bleaker story, however. Apple had earned just over $500 million during 1992, but earned just $90 million in the following year. This was disastrous, especially for a company that was a possible merger candidate for IBM and Sun.

Much of the blame for the sharp downturn in earnings belonged to Spindler. The three PowerBooks were huge hits, not just in the Mac world, but in the business world. The PowerBooks were status symbols in addition to being business tools.

Spindler figured that the desktop convention of waiting 18 months to release a new product would suffice for the PowerBook, but he was wrong. The market was already saturated, and sales nosedived. Spindler actually had to write off thousands of PowerBook 100s, which were sold below cost, at $999 on the west coast and $1,099 on the east coast.

Sculley had one last strategy to save Apple before he made his exit. A Claris employee, Dan Eilers, had made the case for licensing the Macintosh software to outside companies several times in the 80s, but he was always rebuffed by Gassée. With Gassée out of the picture, Eilers proposed that Apple be split in two companies. One would produce hardware, Macintosh Co., and the other would develop the Mac OS and Newton Intelligence, AppleSoft. Sculley liked the plan a lot, since it would make the Mac OS a lot more palatable to any outside hardware company and even a merger candidate.

No one wanted to work at Macintosh Co.

Sculley got approval from the board and hired accounting giant Arthur Anderson to administer the split. He would head AppleSoft, and Spindler would head Macintosh Co. There was a problem, though. No one wanted to work at Macintosh Co. There would be more competition, so the machines would be cheaper and less innovative. As a result, there was little incentive to stick around, especially if the engineers at AppleSoft were able to work with advanced, next generation software, like Taligent.

…the split would probably spell the end

of Apple’s reputation as an innovator.

Spindler was no different. He didn’t want to be stuck with the less innovative Macintosh Co., and he told Sculley as much while he was at a sales conference in Sydney. Sculley was flabbergasted. He was able to convince Diery to head Macintosh Co., but he realized that the split would probably spell the end of Apple’s reputation as an innovator. In late May, Sculley told the board that the split would not happen.

Sculley was in trouble. Spindler had thwarted his last big effort to save Apple and had sullied the financial sheets of the company as well through his PowerBook miscalculation.

Sculley announced that he would retire at the end of the year, but the board was not willing to wait that long. Al Eisenstat, a long time Sculley ally and secretary to the board, began discussing a possible coups against Sculley after the board meeting on June 7, when Sculley announced the sharp drop in earnings. A special board meeting was called ten days later to scrutinize Apple’s financial condition – and possibly to consider a buyout offer from IBM.

Eisenstat found that most of the board members were supportive of removing Sculley, but they needed a candidate. Kevin Sullivan, unsurprisingly, suggested Spindler. Sculley had taken the blame for the failed split up and the PowerBooks, so the board still had a very favorable impression of Spindler, and Eisenstat secured the votes for his elevation to power.

Sullivan was the first to tell Spindler on the plan, and he was jubilant at the opportunity to head Apple. He had only three stipulations: He didn’t want his fingerprints on the coups, his wife (who was very sick at the time) would have to approve, and he would be able to change the board, which was still dominated by venture capitalists who invested in Apple during the 70s and early 80s.

Arthur Rock, a venture capitalist board member, spearheaded the effort. He presided over the meeting, which began at 7:00 a.m. For several hours, the board reviewed financial results. Then Rock asked the two board members who worked for Apple to leave, Al Eisenstat and John Sculley. About ten minutes later, Eisenstat was called back in, and in twenty minutes, Sculley was called in. When Spindler entered the Synergy conference room where the meeting was being held, Eisenstat hurriedly left the room.

Seconds later, Sculley walked out of the room and slumped into the chair in his office. He was told that he would have to resign as CEO (though he would remain chairman) and preside over the launch of the Newton, and then he would be able to retire. He was not told who would succeed him.

A few minutes after Sculley left Synergy, a cool and collected Spindler was called into the boardroom. There was little to discuss, since he had already spent hours with Eisenstat negotiating his compensation package. A few minutes later, he emerged, and, in attempting to console Sculley, told a boldfaced lie. He told Sculley that he had only 15 minutes to decide whether to become Apple’s CEO.

Spindler as CEO

Stress continued to be a problem for Spindler. Shortly after he was promoted, his wife was diagnosed with lymph cancer. A year later, his daughter had a serious accident that resulted in a lawsuit against the Spindlers. Regis McKenna, who had stopped consulting for Apple during the Jobs era, told Spindler that he should quit, “or you’ll end up dead at your desk and two weeks from now, no one will remember who you are.”

Spindler’s first major act as CEO was to push through a radical reorganization. Over 2,500 jobs were cut, almost 15% of the workforce, and the company was totally restructured. Instead of lumping all of product development into one division, the company would now be grouped by market. The only remnant of the old Apple was AppleSoft, which was responsible for operating system development. This flattened the structure and eliminated any possible threats from whoever might have headed product development, formerly the most powerful division at Apple.

The reasoning behind the reorganization was valid. Apple was still growing, and it was the largest computer manufacturer in the world by market share, but Spindler recognized that Apple would not hold that position for long – especially with the new price war between Compaq and Packard Bell that reduced prices by almost 20%.

Spindler decided that Apple would be able to compete in only a few core markets and should not invest in others. SoHo, education, and home were the markets Spindler intended to keep, and he would sacrifice enterprise through inaction.

The other big problem for Apple was research and development. The system was clearly broken. Apple was spending more than Microsoft, and it wasn’t reaping the rewards. Pink, supposedly Mac’s savior, was breathing its last breaths as a spin off. Newton was a failure in the marketplace, and System 7 was unstable and slow.

Spindler appointed a new director to AppleSoft, Dave Nagel, who had worked as a NASA researcher. Nagel culled the projects that clearly had no future (like the Jaguar operating system and a networking package) and attempted to build a sense of discipline in the division’s engineers, but he met only limited success.

The reorganization was not cheap. It cost Apple almost $198.6 million to layoff 2,500 employees, which gave the company a rare quarterly loss of $10 million. Spindler began cutting many of the perks the company’s employees had grown accustomed to. The water coolers were taken out of the building (though restored after an employee outcry), the cafeteria had to start charging for meals, and the employee fitness center started charging $2 a week. Most devastating was the suspension of bonuses and pay raises.

Spindler’s actions destroyed employee morale.

Spindler’s actions destroyed employee morale. Apple’s system software group actually received bomb threats, and employees throughout the company installed a screen saver titled “Spindler’s List”, a reference to those he laid off.

A surprising result of the reorganization was the ouster of Eisenstat. Spindler and Sullivan reasoned that the duties of secretary to the board did not merit over $800,000 a year in salaries plus a bonus, but Eisenstat disagreed. The details of how Spindler had betrayed Sculley came out during an age discrimination suit Eisenstat filed against Apple. The two parties eventually reached an out of court settlement, but coupled with the other cuts Spindler made, his reputation would never recover in the eyes of many employees.

While Spindler was out axing employee perks, the outside world heard practically nothing from Apple. Beyond the age discrimination suit and Sculley’s resignation as chairman, the press devoted little attention to the company. Unfortunately, this was the time where Apple most needed a passionate spokesman telling the computer industry and potential customers that Apple was okay. Spindler was not that kind of leader, though. He had shut down Sculley’s state of the art TV studio across the street from De Anza 7 and made no public appearances for almost four months after he became CEO.

His first speech to the public was at the Seybold Conference on October 20, 1993, and it was a flop. When he spoke outside Apple, he didn’t appear all that passionate or even interested in what he was saying. In a dry monotonous voice, he would read verbatim the speech that was prepared for him and do very little else.

At a time, when reporters were starved for information on the inner workings of Apple and new product announcements, Spindler merely talked up the Mac’s advantages in desktop publishing and how the PowerPC would dramatically improve performance. During the question and answer session immediately following his 9 minute talk, he was hammered by business questions from frustrated reporters. After sidestepping three minutes of hostile questions, he walked briskly out of the building with a reporter in tow.

Luckily for Apple, Spindler did have a keen understanding of what was ailing Apple, but he had little power to change the company. Spindler understood that he had to continue growing market share, just as Sculley had done. Apple’s total market share had grown from 7.5% to 9.5%, and Spindler hoped to grow it even further. He believed that if Apple was able to achieve 15%, it would be able to continue attracting new developers and users easily. If the company didn’t, customers and developers would jump ship to the inexpensive Windows computers flooding the marketplace.

Spindler realized that the much maligned option of licensing the Mac OS would be the only viable option for growing Apple. Bill Gates had been the most vocal proponent when he made this proposal in 1985 while Apple was stumbling. Gassée immediately nixed the idea, but there was no way that Apple could slash prices enough to compete with companies like Compaq and Packard Bell.

Mac Clones

The Power Macs and PowerBooks would occupy the high end of the market, while cloners would produce inexpensive PowerPC-based machines. Spindler reasoned that it would be easy to sign on PC manufacturers. They would get the same profit margins as a standard PC, but they would have the Mac OS and independence from Microsoft.

Gateway 2000 engaged with Apple for several weeks on the possibility of becoming a hardware partner, but Spindler wouldn’t accept the licensing fee that Gateway proposed. The only three companies that Spindler managed to rouse were Radius, Motorola, and Power Computing.

Radius was a longtime Mac peripherals maker, but it would not manufacture its own machines. Instead, it would contract with IBM. Motorola had no presence in the PC market, and Power Computing was brand new. Still, the companies were able to pump out low profit margin Macs, and were still beholden to Apple (which had no intention of losing control of its market like IBM had in the PC world).

Not Good Enough

Without a major hardware company, Spindler began looking for a buyer. IBM was still the number one candidate, but Spindler wouldn’t accept IBM’s very generous offer. IBM would pay $50 a share (Apple was trading at $45). Spindler seemed to think he could do better, and he continued his search. This was partly due to the Apple’s prolific growth during 1994. Growth had gone from 5% during the first quarter of 1994 to 27% during the Christmas season. This was mostly due to the resounding success of the Power Macs, which were released on time, March 24, 1994, and Performas. Spindler felt that with that kind of growth, he could find a better deal for Apple shareholders (and his own ego).

Offers began coming from unexpected places. McKenna had convinced Scott McNealy of Sun to make an offer, along with Silicon Graphics and even Oracle. Spindler turned each down, hoping to find a better deal. This strategy was discredited during 1995, a disastrous year for Apple.

Spindler displayed his disloyalty to his staff at the beginning of the year. Diery had failed to account for a huge pent-up demand for the new Macs in the Christmas 1994 season. Eager to pass the blame to someone else, Spindler had Sullivan (HR director and longtime ally) create a reorganization plan at the posh resort of Pebble Beach. Sullivan created two versions, one with Diery as COO and another with Diery running Apple Pacific, the job he had left to become executive vice president. Spindler chose the latter, and Diery immediately submitted his resignation. Eager to quell the fears of outside investors, the reorganization and resignation were not announced until January.

The other part of the reorganization was an admission of failure on the part of Spindler. He was unable to exercise control over the plethora of divisions, so he returned to a structure very similar to Sculley’s last reorganization, with product development, marketing, manufacturing, sales, and customer relations. Unfortunately, even with the more rigid, hierarchical structure, Spindler was unable to keep control. Projects with no hope of becoming products continued, and so did the many conflicting messages from marketing and sales.

The loss of Diery was terrible for Apple. Diery had made sure that manufacturing didn’t exceed demand and held managers accountable when they failed to meet expectations. Spindler was an excellent strategist and probably would have made a great CEO at some other company, but he didn’t have the assertiveness required to make sure his plans were executed.

Dave Nagel, a former NASA engineer and head of the Apple think tank, ATG, took Diery’s place when he headed product development, but he had little management experience.

Twin PowerBook Disasters

The second disaster for Apple were the much anticipated PowerPC PowerBooks, the Duo 2300c and 5300c. The 2300c was prone to shortages of its specialty hard drive and modem.

The 5300c was even less lucky. The 5300c had received much fanfare at the March 1995 Macworld Expo, but as soon as production began, problems began appearing. The hinges were prone to early failure during quality assurance tests. Worse, a PowerBook exploded at the Singapore plant, and a few days later another did so in Colorado.

The 5300c was even less lucky. The 5300c had received much fanfare at the March 1995 Macworld Expo, but as soon as production began, problems began appearing. The hinges were prone to early failure during quality assurance tests. Worse, a PowerBook exploded at the Singapore plant, and a few days later another did so in Colorado.

The press seized on the “exploding PowerBooks” even though it was later found to have been caused by a faulty Sony battery. What should have been a breakout hit for Apple was an embarrassment.

But that wasn’t the worse sting for Apple that year.

Windows 95

Windows 95 was released on 1995.08.24, exactly 140 months after the Macintosh, and it received a rock star’s welcome. The entire year was packed with speculation over the new software; the press didn’t bat an eye at Apple’s brand new, more powerful Power Macs.

Spindler just assumed that Windows 95 would not be a big deal.

And it’s not like Apple was in the dark on Windows 95. The company had known about the impending consumer version of Windows since 1990, leaving it five years to adopt Pink, Star Trek, or the nascent Raptor/Copland. Spindler just assumed that Windows 95 would not be a big deal.

People inside Apple were beginning to question Spindler’s competence in late 1995. The biggest (and saddest) example of this was Joe Graziano, the CFO Sculley spent $1.5 million to attract from Sun. During an October board meeting in Dallas, Graziano sensed Spindler’s weakness and launched a coups d’etat. He gave a speech on Apple’s woeful financial situation and how the company didn’t have much cash on hand for more screw ups.

After he made the case that Apple was in trouble, he offered to fix it. If the board appointed Graziano CEO, he would reorganize the company and focus exclusively on profitable markets, like the home and education.

Unfortunately, the board was not receptive. The financial numbers that Spindler gave them did not back up Graziano’s valid arguments. Graziano was not very prepared, either. It’s likely the board would have been more receptive if Graziano had come at least with handouts – or even better, graphs and charts.

The board unanimously voted to keep Spindler, and Graziano left in disgrace, despite the fact his bleak predictions had already begun to come true.

After the coups attempt, Spindler knew his days were numbered. Sales did not grow nearly as much as the year before. Market share began to slip. Graziano’s worst fears were confirmed during the Christmas season of 1995.

Spindler and Diery predicted a huge 1995, but when the results were announced for the quarter ending on December 31, their failure was breathtaking. Apple had gone from a 9% market share to 7.4%. Sales had grown to $3.15 billion, but at the expense of profits. In the last quarter alone, the company lost $69 million. Apple was poised to lose hundreds of millions of dollars, a stark reversal from the Sculley days of huge profits.

As a result of the bleak financial results, Spindler cut more jobs, almost 1,300. Apple was in the middle of a diaspora of talent. Former Apple employees, like those of Fairchild in the 80s, were leaving Apple in droves to found new companies, like WebTV. Morale was in the toilet and would not improve until Spindler was out.

Ouster

Spindler’s biggest humiliation occurred at the annual meeting, usually an opportunity for the company to talk up new products and initiatives. The one held on January 23 was not celebratory. Spindler was drilled by belligerent shareholders for Apple’s financial results. For the entire meeting, Spindler sat ashen faced with his heads in his hands and offered meek defenses for his performance (though he did acknowledge that many of the problems Apple faced were because of him).

The board meeting a few minutes after the annual meeting went much worse for Spindler. He didn’t tell investors about Apple’s biggest problem. Much of the growth in 1995 was attributable to “channel stuffing”, where a sales rep pressures retailers to buy more Macs than they can sell. Diery was under the incorrect impression that consumer demand was growing at the same rate as sales. As a result, there were massive surpluses of unsold products around the world. Over $1 billion would have to be sold at a loss, if at all. For a company with $9 billion in sales, this is an incredibly high number.

Spindler believed that this bad news would be deflected by a brand new offer from Sun to buy Apple. Sun was apparently fed up with the protracted negotiations with Spindler and issued a final offer: $25 a share. That was an outrageous price that only a desperate company would accept. Apple’s stock was trading for $31.

It was a no-brainer for the directors: They voted to reject the offer. The effort was spearheaded by relative new comer, Gil Amelio.

The directors buckled down and called an all nighter, then had all of Apple’s major executives give an assessment on their projects and Apple in general. The executives’ talks ranged from apologetic to evasive, but no one had good words for Spindler’s management. The meeting adjourned, and the board scheduled a follow up meeting the following Monday, January 29.

The press was having a field day with Apple, and they still didn’t know about the $1 billion write-off. Venture capitalist celebrity John Doerr commented that “Apple’s management ought to be tried for warcrimes.” Everywhere in the media, the specter of a bankrupt Apple was raised.

Spindler still hoped that he would be spared and allowed to engineer a turnaround, just as Sculley had in 1985. He invited his wife to join him at the meeting, which would be held at the exclusive St. Regis Hotel in New York City.

After a long dinner, Markkula called the meeting to order. Spindler made a speech in his defense. His strategy was good, but he had to work on execution. The board was not receptive, though. Markkula had helped Spindler get the job 15 years before, and he was the one who told Spindler that board wanted his resignation.

This article was first published on 2006.04.06.

Partial Bibliography

- Apple: The Inside Story of Intrigue, Egomania, and Business Blunders, Jim Carlton

- Infinite Loop, Michael Malone

- The Second Coming of Steve Jobs, Alan Deutschman

- Apple Confidential 2.0, Owen Linzmayer

- Odyssey: Pepsi to Apple . . . a Journey of Adventure, Ideas & the Future, John Sculley

- Wikipedia

Keywords: #michaelspindler #peterprinciple

Short link: http://goo.gl/Pt232m

searchword: michaelspindler

I’m really loving these history articles! Keep them coming!

We’re trying to get one posted daily, beginning with the most popular ones in our archive and working our way down the list. We’ve also got a new page in development covering the key players during Apple’s history.

Pingback: Apple’s Mac turns 30: How Steve Jobs’ baby took its first steps – Register | Top Breaking News