The Apple III was meant to be Apple’s bold entry into the business market; it ended as Apple’s first commercial failure and put the company into financial uncertainty. It was also responsible for sprouting both the Lisa and Macintosh projects, efforts that would save Apple.

Wendell Sander, father of the Apple III. Photo courtesy of and copyright by David Ottalini. All rights reserved.

The Apple III project started in late 1978 under the management of Dr. Wendell Sander, with the internal code-name Sara (named after Sander’s daughter). The project was mainly started because Apple didn’t believe its highly successful Apple II line would maintain its popularity.

The Apple III was the first Apple computer not designed by Steve Wozniak. The specifications were defined by a committee of Apple engineers to be implemented by Sander. Apple wanted the III completed in 10 months, but because of extra features constantly being added by the committee of engineers, it took two years.

Nobody doubted the new computer’s success. Many engineers began to feel like geniuses shortly after Apple’s initial public offering when their stock took off. They thought it was impossible for them to fail, no matter what they did.

Jerry Manock designed the Apple II and Apple III casings – and later the Macintosh 128K casing. The corners on both the computer and the keyboard share the 45-degree chamfers that Manock had used for the Apple II, and the same placement of the name badge and identical beige plastic help reinforce the impression that the Apple III is a less frivolous but close relative to its predecessor.

The Apple III chassis was designed by Manock and Dean Hovey (an industrial designer under contract). The chassis was a single, heavy aluminum piece with the power supply enclosed in the left section; it had no ventilation.

The chassis had major faults, and according to Owen W. Linzmayer in Apple Confidential 2.0, Steve Jobs, who supervised the project, didn’t help the situation. He gave the development team dimensions in which components would not fit and demanded the computer not have a cooling fan because they were “too noisy and inelegant”.

The Apple III used its own operating system, SOS (Sophisticated Operating System), which was closed source and used a monolithic kernel. It influenced the design of the ProDOS operating system, which was used on the Apple IIe and later Apple II series computers, and it also influenced the design of the Macintosh Hierarchical File System (HFS).

The main interaction with SOS was through the Apple III System Utilities program. The System Utilities program had three main sections: the Device handling commands section, the File handling commands section, and the System Configuration Program (SCP).

The additional benefit of SOS over older Apple DOS versions was the ability to use device drivers to support devices such as hard drives and RAM drives in addition to 5.25″ floppy drives.

SOS also featured a built-in real-time clock and video capable of generating 24 lines of 80-column text and up to 560 by 192 pixels (in the monochrome graphics mode). The Apple IIIs actual specifications were very impressive and fared very well considering the competition which was getting stronger all the time.

Although SOS had many advantages, it wasn’t backward compatible with DOS 3.2 and 3.3, which is what most Apple II software used; thus the Apple III had hardly any software available for it compared to thousands of titles available for the Apple II.

Great Fanfare

Apple originally promised to ship the Apple III in July 1980, but production problems and internal conflict set the release date back. The Apple III was announced on May 19, 1980, during the National Computer Conference (NCC) in Anaheim, California.

The Apple III was released to much fanfare – Apple rented Disneyland for a day and commissioned bands to play in the Apple III’s honor. Apple was extremely proud of its new product, because it was its first business-orientated computer and also its first departure from the Apple II architecture.

The Apple III used a 2 MHz SynerTek 6502A processor, had 2 KB of ROM, 128 KB on-board RAM (256 KB in the revised model and the III Plus), and could take a maximum of 256 KB. Four proprietary slots were also included, which were compatible with Apple II cards.

Unlike its Apple II predecessors, the Apple III was black and white, not color. However, when connected to a color display it was capable of 4-bit (16 colors) 40 x 48 and 140 x 192. A built-in 5.25″ Shugart 143 KB floppy drive was included, making the main system unit larger and bulkier than the Apple II, which did not include an internal floppy disk drive but used external Disk II drives.

A serial port was available on an optional expansion card, and a built-in mono speaker was standard.

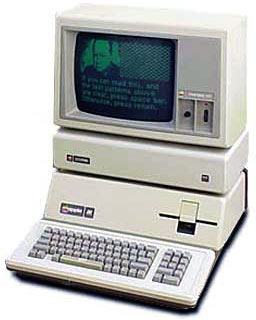

The Apple III was sold in two different configurations ranging in price from US$4,340 to $7,800. The Disk III floppy disk drives and an Apple ProFile 5 or 10 MB hard drive were available as options. The ProFile hard drive sat under the Monitor III in a typical setup (see photo), and required a special interface card, which plugged into an available slot on the Apple III.

Internally, the ProFile used a Seagate ST-506 drive mechanism and a digital and analog circuit board designed and manufactured by Apple. It had an internal power supply. The ProFile cost $3,495 and was an important addition to the system, since IBM didn’t yet offer a hard drive for its PC.

The Apple III was also compatible with the older Disk II floppy drives.

Problems

Two months after introduction of the Apple III, only three software programs were available for it, one of them a mail management program written by Apple’s Mike Markkula. New programs were not expected for six months. The Apple III’s software and hardware were very buggy; it would often crash when using the Save command, causing great frustration to journalists using the computer.

The result of the fault-ridden design was that the motherboard quickly got too hot and warped, causing chips to pop out of their sockets, resulting in severe problems with the entire system.

Dan Kottke, one of Apple’s first employees, discovered the solution to the Apple III’s problem. One day he picked the machine up a couple of inches in frustration and slammed it down on his desk. The III jumped back to life. Kottke knew it was a faulty connector, but he didn’t tell anyone, as he was a “lowly engineer” (the phrase Jobs used to explain why he wouldn’t give him stock options). This was Kottke’s revenge.

Apple’s official suggestion to customers in response to this problem was to pickup the Apple III system and drop it onto a desk to reseat the chips temporarily. As if that wasn’t enough, the built-in real-time clock stopped working after several hours of use, and the Apple II Plus emulation didn’t always work properly.

Wendell Sander’s boss, Tim Whitney, assuming everything was fine with production, told Apple CEO Michael Scott that all was well and the Apple III units would soon be rolling off the manufacturing line. Whitney was meant to stay in Cupertino at Scott’s request, but he left on a business trip to Europe. He returned to be fired and left Apple with his millions.

Enter the IBM PC

Something else was around the corner that would have a major impact on Apple, the Apple III, the computer industry, and the entire world. For the past few years, IBM had been hard at work designing a personal computer targeted at the business market to compete head-on with Apple.

Apple had blown its chance; the Apple III was released a year earlier than IBM’s rival computer, but the III was unreliable and received nothing but bad reviews.

On August 12, 1981, at a press conference at the Waldorf Astoria ballroom in New York City, Don Estridge announced the IBM PC at US$1,565. This was much lower than the release price of the Apple III. IBM, the computer giant, demonstrated the seriousness and potential of personal computing in the business arena. It was now good to go for corporate America.

Thousands of businesses across the US bought an IBM PC, not even looking at Apple as an alternative.

Changes

In February 1981, Apple announced that the Apple III would no longer include the built-in clock/calendar because National Semiconducter’s clock chip didn’t meet Apple’s specifications; however, nobody was willing to explain why it had been included in the shipping product in the first place.

Apple also dropped the price of the Apple III to US$4,190 in an effort to sell more units; it also gave a $50 rebate to customers who had purchased one prior to the price reduction.

After the Apple III had received nothing but bad reviews from the media, Regis McKenna, whom Apple used for advertising, advised Apple to stop all advertising and promotion for the Apple III. The III was completely redesigned, RAM could go up to 512 KB, the clock chip was put back in, and a software library was rushed to completion.

The revised Apple III was launched at the end of 1981, but McKenna refused to promote the III anymore, and it quickly died.

Apple ended up replacing 14,000 bad Apple IIIs with the newly revised system. However, even some of the replacements failed. Of the 7,200 original Apple IIIs that had been sold, 2,000 were replaced for free when the new version became available in December.

Another improved version, the Apple III Plus, which cost $2,995, was introduced in December 1983. The III Plus fixed the hardware problems of the original III, included 256 KB RAM as standard, built-in clock, video interlacing, and featured a keyboard in the style of the Apple IIe.

However, not even the “allow me to reintroduce myself” ad campaign could salvage the III’s reputation. Possibly more relevant in the long run was the fact that the III was essentially an enhanced Apple II – newest heir to a line of 8-bit machines dating back to 1976.

Hindsight

Although many of the Apple III’s faults have been directly attributed to Steve Jobs’ demands and decisions, Sander still said in an interview with David Ottalini in The III Magazine in November 1986:

“For all the comments and pluses and minuses and arguments about many of Steve Jobs’ philosophies, ‘By George it had to be this way and look this way’, I think the current success of the Macintosh, and much of the success of that philosophy has to be credited to him.”

Sander considered that one of the main reasons for the Apple III’s failure was because it was rushed and released six-to-nine months too early.

In April 1981, Markkula had stated in The Wall Street Journal, “The Apple III is designed to have a 10-year lifespan”, although on the same day he admitted to the Apple III’s many flaws: “It would be dishonest for me to sit here and say it’s perfect.” He said later in 1981 that Apple would commit to the Apple III as a major product for the next five to seven years.

The Apple III was discontinued on April 24, 1984, and the III Plus lasted a mere four months after its introduction in 1983. In total, only 65,000 units were sold. According to Steve Jobs, lost Apple “infinite, incalculable amounts” of money on the Apple III (Playboy, February 1985). Apple lost over $60 million on the line and quietly removed it from its product list in September 1985.

Nearly Worthless Today

Today, used Apple IIIs are valued at around $50-250 depending on condition and extras. Sun Remarketing continued to sell the Apple III for ten years after its discontinuation – for as low as $249, according to its 1991-92 catalogue.

Although Apple should have learned lessons from the chaos the Apple III caused, they later attempted the business market again with the Apple Lisa in 1983, only to fail again, this time owing to the Lisa’s $10,000 price tag and several technical problems.

This article was originally published on 2006.09.01.

Online Resources

- Apple III, Wikipedia

- Infinite Loop, Michael Malone

- Apple /// & ///+, Apple History

- Apple III, Old Computers

- Apple Confidential 2.0, Owen W. Linzmayer

- 2 Apple Failures: Apple III and Lisa, Tom Hormby, Orchard, 2005.05.16. Apple’s two not-so-great product lines between the Apple II line and the Macintosh.

- The Ill-Fated Apple III, Jason Walsh, Apple Before the Mac

Keywords: #appleiii

Short link: http://goo.gl/sCycxP

searchword: appleiii