Apple’s Lisa was first envisioned as a brand new business computer to succeed the very popular Apple II, and it was to be designed by Steve Wozniak. The project was quickly turned over to Ken Rothmuller, a former HP director, as Wozniak drifted away from Apple.

A marketing specification was completed and approved in 1979, but the planned Lisa bore little semblance to the computer that would eventually be released. To be sold for no more than $2,000, the Lisa was to have a green phosphorous CRT, a 16-bit processor, and a high capacity floppy drive. The project was to be ready for release in 1981.

A marketing specification was completed and approved in 1979, but the planned Lisa bore little semblance to the computer that would eventually be released. To be sold for no more than $2,000, the Lisa was to have a green phosphorous CRT, a 16-bit processor, and a high capacity floppy drive. The project was to be ready for release in 1981.

The first thing Rothmuller realized was that it would be impossible to meet the 1981 deadline. He expressed his doubts to Steve Jobs, but he did not get the reaction he expected – he was removed from his position as manager of the Lisa project and replaced by another HP manager, John Couch.

Jef Raskin, the manager of the Macintosh project – which was proposed around the same time – came to the Lisa team to help out while his proposal awaited approval. Work on the Lisa was slow, and by late 1979 the team had not even selected a processor to base the machine on. The engineers were not particularly motivated to churn out another product so similar to the Apple II.

Xerox PARC

Raskin, who had visited Xerox’s fabled skunkworks, PARC (Palo Alto Research Center), several times while he was at Stanford’s Artificial Intelligence Lab, began suggesting to Jobs that Apple visit the labs for inspiration. He was rebuffed by Jobs, who disliked Raskin, but Jef was not discouraged. He convinced a mutual friend, Bill Atkinson, to suggest the idea to Jobs, and he accepted.

Since its inception, Xerox had given other companies tours of PARC, showing off the highly advanced Alto workstation, which had a bitmapped display, an object oriented programming environment, was networkable, and was more powerful than most minicomputers of the day. (The researchers at PARC had since become leery of outsiders and stopped giving tours.)

Since its inception, Xerox had given other companies tours of PARC, showing off the highly advanced Alto workstation, which had a bitmapped display, an object oriented programming environment, was networkable, and was more powerful than most minicomputers of the day. (The researchers at PARC had since become leery of outsiders and stopped giving tours.)

Convinced that the technology at PARC could help Apple usher in the 1980s, Jobs offered Xerox a killer deal: Apple, which was privately owned at the time, would allow Xerox to invest $1 million in Apple, which was sure to soar in value when the company went public in 1981 – in exchange for two guided tours of PARC’s technology. Xerox happily accepted and gave Jobs and a team of Lisa project engineers a tour.

Jobs (who took only Atkinson along on his first visit) had a rather limited understanding of technology and was most impressed by the graphical interface he saw running on the Alto. The interface was not similar to today’s interfaces, but it was a huge jump forward from the command line interfaces used everywhere else.

A New Vision

When the engineers returned, they had a vision of what they wanted in the Lisa project. Apple’s chairman was so impressed that he interrupted a demo given by Xerox’s Larry Tesler, asking him why nothing was being done with the technology.

For the second visit, Jobs brought along several members of the Lisa project and was given a much more technical demonstration. The other engineers who went on the second visit, who were briefed by Raskin before their visit, were equally impressed.

For the second visit, Jobs brought along several members of the Lisa project and was given a much more technical demonstration. The other engineers who went on the second visit, who were briefed by Raskin before their visit, were equally impressed.

The Apple engineers were not the only ones impressed by the visit. The researchers at Xerox, long discouraged by Xerox’s inability to release a product based on the technology developed at PARC, were impressed by Apple’s seeming willingness to implement advanced technologies in their products.

The Lisa project changed dramatically. No longer was it to be a mere hardware upgrade to the Apple II line. The new focus of the Lisa project was software. The team wanted to implement all of the innovations they saw at PARC.

Trip Hawkins, the marketing and planning manager for the Lisa project, rewrote the product specification to include a graphical user interface, a mouse, an object oriented user interface, and networking, as per Jobs’ wishes. With the revitalized Lisa project, PARC researchers began to jump ship en masse to work on Apple’s project. The first was Larry Tesler, who would be joined by 15 other Xerox employees before the release of the Lisa.

Windows with Rounded Corners

Bill Atkinson left the two PARC visits with an idea for the Lisa. While Tesler was giving a demo, Atkinson thought he saw the Alto displaying windows with rounded corners and was baffled at how the feature was implemented without sacrificing performance. This set off a multi-month obsession to find out how Xerox had implemented the feature, only to be interrupted by an auto accident.

Atkinson implemented round corners (it’s part of the original QuickDraw toolbox) and later found out that the PARC developers had never even considered implementing such a feature. All of this was implemented long before there was a fully functionally Lisa prototype.

Jobs took a more and more active role in the Lisa project, and he eventually appealed to Apple CEO, Mike Scott, to appoint him head of the group, displacing the well qualified John Couch. Scott had little confidence in Jobs’ management abilities and did not want to put him on such an important project, so he kept Couch in control.

Jobs Takes Over the Macintosh Project

Jobs did not want to take the “consolation prize” of company spokesman, a position he was more qualified for than project manager, and eventually took control of the Macintosh project from Jef Raskin. Jobs maintained a grudge against the Lisa until it was discontinued.

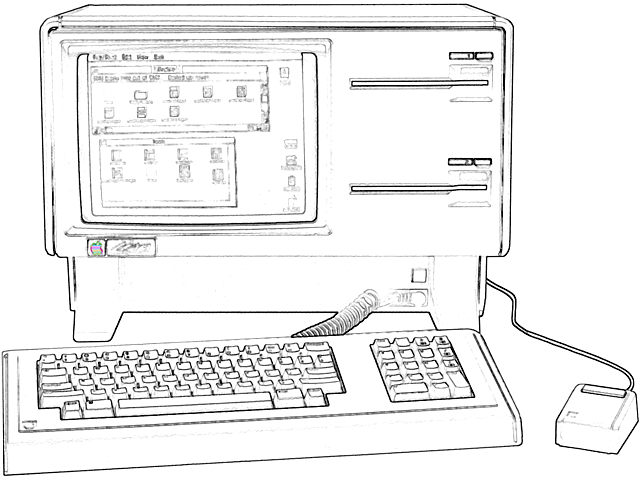

The first and most important task of the team did not involve software at all. The group decided that a 16-bit processor would be necessary to power the bitmapped display and other processor-intense interface features. After considering several different processors, including the 8088 and Z8000, the team decided to use the Motorola 68000, a chip that provided performance comparable to a mini computer.

A more problematic decision was the floppy drive. While Jobs was still with the project, he insisted that the Lisa use Apple’s 5.25″ “Twiggy” floppy drive. These unusual drives were very unreliable, but the engineers decided to keep them, assuming the reliability issues would be solved.

A more problematic decision was the floppy drive. While Jobs was still with the project, he insisted that the Lisa use Apple’s 5.25″ “Twiggy” floppy drive. These unusual drives were very unreliable, but the engineers decided to keep them, assuming the reliability issues would be solved.

The Lisa was to be housed in a very approachable (almost cute) case. The CRT and CPU were housed in the same case, which had two feet protruding from the front. The innards were very accessible: The mainboard was mounted in a rack that allowed users to pull out the entire thing after taking out three screws, making it easy to service it.

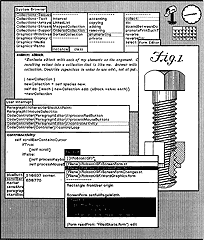

For all the innovation at PARC, Xerox’s software was bewilderingly difficult for computer novices to use. Lisa’s engineers were not interested in duplicating the Alto’s software features. They wanted to extend and add on to them.

Usability

The Alto was still just a multi-million dollar prototype. The key differences between the projects was the Lisa team’s dedication to ease of use. After a major interface feature was implemented, Larry Tesler would always recruit an initiated Apple employee to test it out. If the employee could figure it out, it stayed; if the employee could not, it was redesigned.

The principle difference between the Alto and the Lisa was that the Lisa had a desktop interface. Dan Smith, a major contributor to the desktop interface, had created the Lisa’s first interface, the Filer. The Filer asked a user a series of questions about what task the user wanted to accomplish, and when enough questions were answered, the tasks were executed, and then the Filer shrank to the background. The entire operation was very fast for experienced users, but it tripped up the type of customers Apple hoped to win with the Lisa, those who were not already computer users.

Smith realized this when he brought a Lisa prototype home and showed it to his wife. She was completely stumped by the Filer, and Smith knew that he had a problem.

This was mid-1982, and Smith feared that there would not be enough time to implement a new user interface. When he brought his problem to Bill Atkinson, Atkinson had an idea. Instead of involving the project’s management, he recruited another engineer, Frank Ludolph, to spend a weekend at Atkinson’s home in an extended crash session. By Monday morning, a preliminary version of Desktop Manager was ready for review by Atkinson’s boss, Wayne Rosing, who was thrilled with the change.

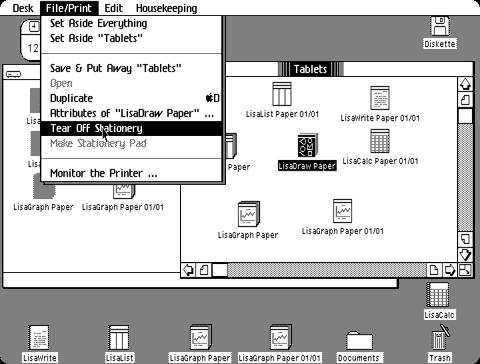

Screenshot courtesy of ToastyTech.

Document Centered

Desktop Manager’s most notable difference from its peers (and most computers today) was that it used a document-centric interface. Users never opened or closed applications; they opened documents or created new ones from stationary. When users were done with a document, they would put it away, and the document would minimize to the file icon. This made the machine much more approachable by those who did not understand the concept of files or applications.

The biggest investment Apple made in the Lisa was not into the operating system, it was in the large suite of applications every Lisa shipped with. More than half of the software developers worked on perfecting the office suite that would be the focus of most users while they used their Lisa.

Seven applications, dubbed the Lisa Office System, were bundled with the operating system: LisaWrite, LisaCalc, LisaList, LisaProject, LisaDraw, LisaPaint, and LisaTerminal. All of these applications took full advantage of the document-centric the Lisa interface, and they were held in better regard by reviewers than the Lisa operating system itself.

By 1983, the Lisa was ready. The marketing department planned a huge publicity campaign (one that would be dwarfed a year later with the Macintosh) that pushed the Lisa onto the national stage. Time and Newsweek did big write-ups on Apple and the Lisa, and advertisements were taken out in large trade magazines and newspapers touting the Lisa revolution.

By 1983, the Lisa was ready. The marketing department planned a huge publicity campaign (one that would be dwarfed a year later with the Macintosh) that pushed the Lisa onto the national stage. Time and Newsweek did big write-ups on Apple and the Lisa, and advertisements were taken out in large trade magazines and newspapers touting the Lisa revolution.

Launch

By June it had all reached a fever pitch, and the Lisa was released. The price was set at $9,995, unheard of at the time, but necessary in John Sculley‘s eyes to recover the millions of dollars invested in the machine. (Sculley had recently been recruited as CEO by Jobs.)

For the latter half of the year, the Apple met Lisa sales expectations and sold 13,000 computers. But in 1984, when Apple expected to sell 80,000, the company sold only 40,000. Sales would drop even further behind expectation in 1985.

The biggest reason was price. The software and hardware was spectacular when compared to even the highest-end PCs (even if the Lisa was a little sluggish), but the Lisa was priced well out of their range and had to compete with Wang, DEC, and Xerox – not to mention Apple’s own Macintosh, which was released in 1984.

Apple was trying to sell a workstation like a personal computer. By 1986, after several revisions and price cuts, the Lisa was discontinued.

Bibliography

Some of the sources used in writing this article.

- Apple: The Inside Story of Intrigue, Egomania, and Business Blunders, Jim Carlton

- Infinite Loop, Michael Malone

- The Second Coming of Steve Jobs, Alan Deutschman

- Apple Confidential 2.0, Owen Linzmayer

- Odyssey: Pepsi to Apple . . . a Journey of Adventure, Ideas & the Future, John Sculley

- Wikipedia

Apple Lisa group on Facebook.

Short link: http://goo.gl/WiIdEC

searchword: lisahistory