Realizing that the Apple II would not sustain Apple forever, the Sara project began. The main idea of Sara was to create a more powerful and capable Apple II. It would include 128 KB of RAM, an integrated floppy drive, and a high resolution display – 80 columns wide instead of the Apple II’s 40.

![]() Most importantly, the machine would natively recognize uppercase and lowercase characters.

Most importantly, the machine would natively recognize uppercase and lowercase characters.

The leadership at Apple wanted to release this machine soon – in just 10 months. In September 1980, the machine’s name changed from Sara to Apple III. The machine ran a brand new operating system, SOS (Sophisticated Operating System) and was equipped with a new version of BASIC, Business BASIC.

The Apple III was released to much fanfare – Apple rented Disneyland for a day and commissioned bands to play in the Apple III’s honor.

It turned out that the Apple III was not worth the fanfare. It had a far more sophisticated design than the Apple II, but in order to remain compatible with the Apple II, it had to retain the underpowered MOS Tech 6502 processor. Because of this, the machine offered few compelling features, and businesspeople were hard pressed to justify the expensive machine.

The machine’s manufacturing was also not up to snuff. The built-in clock, not present in the Apple II+, would fail after a couple hours of use. On top of that, Steve Jobs’ insistence that the machine have no fan made for a very hot mainboard. After being used for a day or two, the computer would get so hot it unseat some of the chips. Apple refused to install a fan to fix the problem and instructed users to drop the machine on their desk to bang the chips back into place. [Editor’s note: Not a big drop – just a few inches.]

Apple eventually resolved these problems in the Apple III+, whose marketing slogan, “Allow me to reintroduce myself”, failed to rescue the machine’s reputation. By April 1984, Apple had managed to sell only 65,000 units, losing money on the model.

Research at PARC

While IBM toiled away at Chess, its new personal computer, Apple created the future of computing.

Xerox’s research lab in Silicon Valley, PARC (Palo Alto Research Center), was creating incredibly advanced machines that the company was never able to market properly – or sometimes market at all. Xerox refused to think there would be a market for the technologies developed there, including laser printers, email, ethernet, the GUI, the first graphical word processor (Bravo, which was not as friendly as MacWrite but was more friendly than VI), and the bitmap display.

A legend at PARC, Alan Kay wanted to make computing accessible. He wished to create a computer for $500 that had the power of a computer the size of a gymnasium. He called his idea Dynabook.

A legend at PARC, Alan Kay wanted to make computing accessible. He wished to create a computer for $500 that had the power of a computer the size of a gymnasium. He called his idea Dynabook.

In 1967, his visions began to materialize into reality with the creation of FLEX. FLEX was a powerful computer language capable of using windows, a mouse, and a very high resolution display. Kay joined PARC in 1971, where he led a dozen engineers (including future Apple Vice President Larry Tesler) in the Learning Research Group.

The group’s first project was to create a programming language. Kay wanted a programming language so simple and fun that a child would enjoy using it. The group designed the language to rely less on the typed word and more on the mouse and display. Programmers could drag and drop programs together. The group named the language Smalltalk.

Others at PARC had created Alto, a very powerful microcomputer, as powerful as the popular Nova minicomputers available at the time. The Alto was laced with innovation. It had a high resolution display and an ethernet interface, which allowed these computers to share resources.

Others at PARC had created Alto, a very powerful microcomputer, as powerful as the popular Nova minicomputers available at the time. The Alto was laced with innovation. It had a high resolution display and an ethernet interface, which allowed these computers to share resources.

More importantly, the Alto’s software was not designed around the command line; it was designed around its bitmap display. Users manipulated the mouse to initiate commands, not the keyboard. The user was no longer limited to a finite number of decisions presented by a program (an on-screen menu of choices). The user could now choose to work on any part of a document or open any type of file.

Another important aspect of the Alto was its display. Its high resolution display allowed it to display characters just as they would be printed. The concept of WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) had been born. Alto’s commercial successor, the Star, would make use of this feature heavily. It was marketed almost exclusively to graphic designers and type setters.

Birth of Lisa

Apple had two active projects underway, Lisa and Macintosh. The two projects were meant to complement Apple’s product range, not replace the Apple II, which received several updates (the Apple IIe and the Apple IIc, which was arguably the first successful portable personal computer).

Steve Jobs led the Lisa project, and Jef Raskin led the Macintosh design team. Jobs was still not aware of the miracles being born at PARC and did not incorporate those changes into the design of the Lisa.

The first Lisa prototypes were completed in December 1979, but they did not satisfy Jobs. They were just more advanced Apple IIs and did not offer many new features.

Apple Goes Public

On December 12, 1980, Apple went public. Each share sold for around $22. Before this, Apple had given stock only to employees, but they were now available to the world. The 4.6 million shares up for sale were gone in a few minutes. Apple had made over $100 million for itself and had made many of its employees, most of whom were under 30 years old, millionaires. Porsches and other luxury cars invaded the parking lot.

The sale inspired some tensions between employees. The earliest employees were given more shares and much more money than newer employees. Some had sold their shares or given them away and were stuck with their ordinary salary while their peers became very wealthy.

This rapid growth led Apple to secure its facilities. It issued all of its employees ID badges, which had to be presented upon entry. The Apple executives also feared that they had expanded too quickly and pushed through the layoff of 40 engineers. That day, February 25, 1981, became known as Black Wednesday.

Despite this, the general mood at Apple was still pleasant. All of the employees were looking to the future with hope. At this point, Steve Jobs pulled off two “miracles” – first, he gave Xerox $1 million in Apple stock in exchange for access to PARC’s research. At the same time, he oversaw the the opening of European offices in Paris and Slough (Britain).

The person charged with organizing the visit with Adele Goldberg was apprehensive about allowing Apple to use PARC’s research. She felt Xerox was better suited to market PARC’s innovation than Apple was, but she led the tour despite this.

The Apple employees were awestruck They loved the icons and the mouse and the elegant interface. Steve Jobs decided that the Lisa would be the Alto “for the people”. A few months after the visit, 20 PARC employees jumped ship and joined Apple on the Lisa team.

Bill Atkinson was another important addition to Apple’s team; he quit his graduate studies at University of Washington in Seattle to join Apple in 1978 and would design much of the graphics subsystem for the Lisa and Macintosh, as well as creating HyperCard.

Macintosh

During the spring of 1979, Jef Raskin and his team set to work on Annie while Steve Jobs led the Lisa project. Annie was not intended to compete with the Lisa and Apple III. Instead, Raskin envisioned it as a competitor to the popular game consoles and home machines of the time.

Raskin was not enthusiastic about making a machine as complicated as the Apple II, so he decided to design the machine with what he would later term “a humane interface”. Besides the user interface, Raskin also decided not to include an expansion bay.

The machine was to be an all-in-one model. The monitor, keyboard, and floppy drive were all integrated into the case. Even more unique, the machine was to include a battery to run the machine for around two hours.

Raskin decided on fairly high-end specs. It would be equipped with 64 KB of RAM, modem and printer ports, a 200 KB floppy drive, the programming languages FORTH and BASIC in ROM, and an operating system equipped with a humane interface.

The team hoped that the machine would require no software manuals.

The project was soon renamed Macintosh, which was just a codename. It was intended to be called the Apple V.

Steve Jobs, still the leader of the Lisa team, disparaged the Macintosh project. The Lisa was becoming more and more expensive and ambitious, and several team members believed that it would never see the light of day.

Along with the increased pessimism of the Lisa team, Jobs began appreciating the Macintosh. Eventually, he decided that he would leave the flagging Lisa project and become the leader of the Macintosh team. Raskin, however, remained in control. The machine was now expected to cost between $500 and $1,000.

Raskin called upon Bill Atkinson, a member of the Lisa team, who introduced Burrell Smith, an Apple II service tech, to the project. Steve Wozniak also joins the project, helping design the mainboard of the machine.

After being ousted from the Lisa project, Jobs set his sights on the Macintosh project. The Apple board members were all glad to see that Jobs was no longer leading the vital Lisa project. Jobs installed himself at the head of the Macintosh project, which was still intended as a low-end personal machine. He started to remake it to become what the Lisa couldn’t be. He even tried to change the name from Macintosh to Bicycle, though nobody agreed with him.

Convinced that the Macintosh was near to release, Jobs made a $5,000 bet with the leader of the Lisa group that the Mac would be ready before the Lisa.

In 1982, Jobs gathered the signatures of all of the creators of the Macintosh to be engraved into the interior of the case.

The Lisa was released first – and to some fanfare. Apple had lined up several software makers to produce software for the Lisa, but these titles were largely absent at the time of the launch. Luckily, Apple included a full featured office suite, so most users rarely needed third party software.

The initial excitement of the machine wore off fairly quickly. It was like a Xerox Star 8010 with fewer features and a similar price tag.

Despite the lukewarm reaction to the Lisa, the Macintosh team pressed on. One of the most significant changes in the creation of the Macintosh was use of the 68000 processor, the same CPU that the Lisa used. Raskin hesitated, fearing the new complexities that such a powerful processor introduce. Jobs decides that the processor could make the Macintosh more like the Lisa, which was what he wanted.

Raskin ended up resigning after the new processor was adopted. Jobs became somewhat tyrannical, demanding that all decisions in the project pass through him. The engineers eventually learn to hide new features from Jobs until they got them to a point where they were either already in the machine or so convincing that Jobs could not turn them down. That is how the 3.5″ floppy drive was included (instead of 5.25″), along with the possibility of expanding the RAM in the machine.

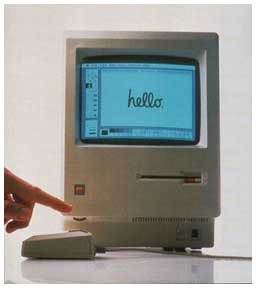

After two years of delay, Apple released the Macintosh on January 24th, 1984. The price was long contested in the upper levels at Apple. They eventually settled on $1,995 – until John Sculley decided that he wanted a huge advertising blitz to accompany the machine, so the machine was priced at $2,495.

After two years of delay, Apple released the Macintosh on January 24th, 1984. The price was long contested in the upper levels at Apple. They eventually settled on $1,995 – until John Sculley decided that he wanted a huge advertising blitz to accompany the machine, so the machine was priced at $2,495.

The launch of the Macintosh was accompanied by the 1984 advertisement, based on the novel of the same name. Apple went far beyond the traditional advertising methods when it also released the machines early to dealers to set up demonstration stations – and gave away machines to personalities including Andy Warhol, who later endorsed the Amiga, and Mick Jagger.

The launch of the Macintosh was accompanied by the 1984 advertisement, based on the novel of the same name. Apple went far beyond the traditional advertising methods when it also released the machines early to dealers to set up demonstration stations – and gave away machines to personalities including Andy Warhol, who later endorsed the Amiga, and Mick Jagger.

The public was fond of the machine’s design. It was compact, had a high resolution display, and included high quality software.

The mouse was also included and was used to navigate the innovative interface that used a metaphor of a desk. Users opened folders, threw documents in the Trash, and could move files and folders around on the desktop.

The press declared the machine and its software revolutionary. In a matter of months, the Macintosh had revolutionized Apple and the computer business.

Further Reading

- Apple II

- Apple III

- Apple III Chaos: What Happened When Apple Tried to Enter the Business Market

- Xerox PARC, Wikipedia

- Alan Kay, Wikipedia

- Larry Tesler, Wikipedia

- Smalltalk, Wikipedia

- Xerox Star, Wikipedia

- Xerox Star 8010

Bibliography

Some of sources used in writing this article:

- Apple: The Inside Story of Intrigue, Egomania, and Business Blunders, Jim Carlton

- Infinite Loop, Michael Malone

- The Second Coming of Steve Jobs, Alan Deutschman

- Apple Confidential 2.0, Owen Linzmayer

- Odyssey: Pepsi to Apple . . . a Journey of Adventure, Ideas & the Future, John Sculley

- Wikipedia

Keywords: #appleiii #applelisa #6502 #6502cpu #mostech6502 #68000

Short link: http://goo.gl/v6ak5S

searchwords: appleiii, applelisa