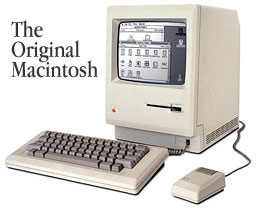

Despite an enormous launch campaign, the Macintosh was a failure. Steve Jobs had predicted that Apple sell 500,000 Macs the first year, but by 1985.03.11 the company had sold only 10% of Jobs’ original prediction.

What’s worse, Jobs was misbehaving. After Apple’s 1984 reorganization, the Macintosh and Lisa teams were merged into a division called SuperMicro. Inexplicably, Jobs was given control.

He probably made matters much worse during the first meeting of the new division by announcing that the Lisa team “really fucked up”. Jobs had instantly alienated some of the most talented engineers in the company and had stunned members of his own team.

John Sculley, who had been CEO for only a year, wasn’t ready to castigate Apple’s chairman and largest shareholder, so Jobs was allowed to continue.

Beyond the Mac

Jobs’ top priority was to create the successor to the Macintosh and to create a network for existing Macintoshes.

The Age of the Workstation was beginning, and companies like Sun were experiencing explosive growth. The next generation of workstations were dubbed “3M” because they had a Megabyte of RAM, Megapixel displays, and Megaflop performance.

The replacement for the Macintosh 128K and 512K was dubbed BigMac; it would be a 3M workstation in disguise, but it wouldn’t cost any more than an average personal computer.

The replacement for the Macintosh 128K and 512K was dubbed BigMac; it would be a 3M workstation in disguise, but it wouldn’t cost any more than an average personal computer.

The most interesting part of BigMac was the software it would run: Unix with a Macintosh virtual machine. Jobs had Apple acquire a very expensive Unix license from UniSoft, but very little progress being made.

The other program that Jobs was spearheading was Macintosh Office, a very ambitious networking system for the Macintosh. The system was inspired by the visits that Jobs and the Lisa team had made to Xerox PARC in 1981, where they saw the ethernet network that linked the Altos into a proto-intranet with email, shared printers, and file shares.

Macintosh Office was going to include a file server, a printer, and a brand new networking protocol. Ideally, BigMac would serve as the hub of the Macintosh Office, allowing third party developers to create custom servers for the network and Macintosh applications. By late 1984, work on the networking protocol and printer was complete, but the file server software and BigMac hardware would never be completed.

The Macintosh plants in Boulder, Colorado, had fallen silent as demand plummeted. Even with the reduced production schedules, there were millions of dollars in unsold inventory around the world.

Standing Against Jobs

Sculley was not yet willing to counter Jobs’ Macintosh strategy, but there were people willing to stand up against Jobs. His own marketing manager, Mike Murray, who had backed Jobs on the 1984 ad, favored removing Jobs and placing him in control of research and development, where he would be able to work on projects with little bearing on Apple’s short term financial performance.

The board of directors, which had made it clear to Sculley that his primary task was to contain Jobs, decided to act, and on 1985.04.11, Arthur Rock, an early Apple investor, told Sculley that if he did not restrain Jobs, he and Jobs would both be fired. Sculley reacted by removing Jobs as the head of the Lisa and Macintosh group, replacing him with Jean-Louis Gassée, a colorful Macintosh marketer from France.

Nothing could be more galling than seeing Gassée seize control of the Macintosh, the group that Jobs had devoted years to – especially since Gassée was the antithesis of Jobs’ understated cool. Jobs would wear tailored Italian suits; Gassée would strut around the executive suite in leather jacket and pants. Jobs had quoted Bob Dylan in the unveiling of the Macintosh; Gassée made dirty jokes with the secretaries.

A Failed Coup

Jobs began plotting a major reorganization/coup that would split Apple into four different divisions. Sculley would be in control of the retail division, where he could capitalize on his expertise in brand management from his Pepsi days, but Jobs would be chairman.

Days after the Gassée promotion, Sculley left for China, and Jobs acted on his plan.

Jobs shared the plan with all the major executives in the Lisa and Macintosh groups, including Gassée, hoping that he would be able to rally support behind his cause. Gassée felt no loyalty towards Jobs and reported the plot to trusted Sculley ally and corporate lawyer, Al Eisenstat. Eisenstat, in turn, made a trans-Pacific telephone call to alert Sculley to Jobs’ machinations. Sculley was enraged and returned to Cupertino, snubbing the president of China over a palace coup.

During an emergency meeting of all the company’s important executives, Sculley harangued Jobs for three hours. Sculley wanted Jobs out of Apple altogether. He took a tally of how many of the executives supported Jobs and how many supported Sculley. The vote was unanimous in Sculley’s favor.

The next morning, Jobs drove to Sculley’s house with his reality distortion field running at full kilter and took Sculley on a long walk in the mountains, just as he had in 1983 when he was courting Sculley to move to Apple. Jobs convinced Sculley that he was only acting in the best interests of Apple. Personal ambition had nothing to do with his plans.

Amazingly, Sculley was under the impression that Jobs was telling the truth, though he insisted that Jobs would not return to any real position of power at Apple. Instead, he would function as a corporate mouthpiece, granting interviews and heading a think tank or research group.

That afternoon Jobs had all of his allies at Apple at his expansive Spanish manse and was discussing strategies for Jobs being reinstalled as head of the SuperMicro group. Towards the end of the afternoon, Mike Markkula showed up, and Jobs’ lieutenants presented their plans. Markkula was not swayed and immediately phoned Sculley to tell him what was going on.

On 1985.05.28, Sculley’s patience ran out. With the support of the board, he stripped Jobs of all his power at Apple. Jobs could stay with Apple, but he would have no sway over operations.

Jobs was heartbroken. Murray was worried for Jobs’ safety, and after no one picked up the phone at Jobs’ manse, he drove over to make sure Jobs was okay. Murray found Jobs lying on a mattress in his unfurnished bedroom, sobbing.

Jobs showed up for work the next morning, but his new role was extremely distasteful to him. Before this, he met with dozens of people every day, giving advice, approving budgets, approving designs, and reading dozens of memos about Apple’s internal affairs. Now nobody sought out his advice, and the memos stopped coming.

Eager to take his mind off his embarrassing demotion, Jobs began a tour of Europe promoting the pending Macintosh Office. After that, he would promote the Apple II in Russia (the US government had only recently approved exports of the Apple II to the USSR, though Mikhail Gorbachev was rumored to be a Macintosh user).

Jobs stayed in Europe for most of the summer and was determined to not let Sculley put an end to his career.

NASA had recently started accepting applications for civilian astronauts to fly on Challenger three years later. Jobs was rebuffed. The government was not going to put a celebrity in space.

His next plan was to leave Apple altogether. He wanted to create hardware exclusively for students – an interesting choice for a man who hadn’t completed a single year of college. He was not just interested in the educational market; he wanted to prove that he didn’t need Apple or any adult supervision to succeed.

When he returned to Apple, his resolve was steeled. His office had been moved into a building on Bandley Drive that was completely empty, except for his secretary. He dubbed the building “Siberia” and stopped showing up for work.

Jobs’ Departure

On 1985.09.12, Jobs wasn’t completely sure what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. He vaguely wanted to stay in computer hardware, and he wanted to market that new hardware to college students, as Apple had done with the Macintosh.

There was one thing he did know for certain, and it was that he couldn’t build his computer at Apple. He had tried with the BigMac and was thwarted by the exhausted and depleted engineering staff, and when he tried to seize control and divert resources and talent to his division, he was rebuffed.

During the board meeting called that day, Jobs revealed his plans to found a new company to the shocked body. The ineffective manager they held responsible for the slow sales of the Macintosh and internal strife at Apple suddenly turned into a threat to Apple’s survival. Longtime investors, including Arthur Rock and Mike Markkula, were terrified by the terrible publicity that Jobs would cause if he left Apple for a startup – and of the effects that negative publicity might have on Apple’s stock price.

John Sculley was the only one not offended by Jobs. He resented the power that Jobs still held over the company (even after his reorganization that removed Jobs from any meaningful position).

Perhaps Apple could make a major investment in Jobs’ new company and maybe even market its products under Apple’s brand. Jobs agreed to think about accepting an investment from Apple and left the headquarters for good – he wouldn’t return for more than a decade.

Over the previous six months, Jobs had kept in contact with some of the senior staff in the Macintosh division, even after Gassée took control. Five of these staffers agreed to become cofounders of the new company with Jobs. Chief among these were Bud Tribble, Susan Barnes, and Dan’l Lewin.

Tribble, a senior staffer at the Macintosh division, was the Mac’s first software manager and the man responsible for the Mac’s shift from the 6809E processor to the 68000. Susan Barnes was the executive in control of the Mac’s finances and budgeting. The most influential staffer that Jobs took with him was Dan’l Lewin, who ran the Apple University Consortium, the sales team that won Macs a significant presence in the university market.

NeXT

The five cofounders left Apple early on Friday, September 13, 1985 (after Jobs gave Sculley a list of the staffers who would leave with him and his own resignation letter, which he had already released it to the media) and joined Jobs at his manse for a dinner of fresh pasta. The cofounders all found the experience eerie. The palatial house was almost entirely unfurnished, sprinkled with a few hyper-expensive leather sofas and a Bang & Olufsen stereo.

Over dinner they discussed whether or not to accept an investment from Apple, which markets they would target, the name of the company (they decided on NeXT Computer, Inc.), and whether or not Apple would sue the group. Jobs had a high power Palo Alto lawyer, Larry Sonsini, make a presentation on that subject.

This was a very real threat. Jobs was the only one who had officially resigned from Apple; the rest were still employees. Beyond that, they were all very senior staffers, privy to confidential plans and projects. They all decided that they would have to resign and did so on the next business day, Monday, September 16.

Word of the resignations quickly got back to Apple and incensed the coterie of executives who reported to Sculley – but not Sculley himself.

A senior staff meeting, which had been planned to discuss the board meeting, was chaos. Bill Campbell and Jean-Louis Gassée wanted to know whether the resignations would stop or whether NeXT would continue to leach staffers from Apple.

Sculley still didn’t perceive much of a threat from NeXT, probably because he was not familiar with the SuperMicro division, but he was overridden by the other executives. They unanimously wanted to sue NeXT for copyright infringement. Another meeting was held the next day to start planning for a lawsuit against Jobs and NeXT.

Despite the fact that Apple saw NeXT as a dire threat to its business, Jobs and the rest of the cofounders had little idea exactly what their company would produce.

Perhaps a result of his own abortive college career, Jobs was fiercely interested in creating hardware for universities and colleges. In fact, one of the few groups at Apple having a great deal of success selling the Mac was the Apple University Consortium. In his role as chairman, Jobs was regularly invited to symposiums and expos for education buyers to promote the Consortium.

Jobs said he was most inspired by a conversation he had with Paul Berg in 1984. The two had met a Stanford hosted lunch held for the visiting François Mitterrand. Awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for his DNA research, Berg explained his goals for personal computers in the classroom.

Berg wanted to make recombinant DNA experiments accessible to freshmen while making cutting edge research less expensive by eliminating wet labs, where DNA was physically extracted from cells and manipulated with virii. He told Jobs that such an advance would accelerate research many times over and help students everywhere (even those in high school) understand DNA. Jobs managed to convince Berg to meet him again at a café near the campus to elaborate on his needs for a computer.

Berg believed that a 3M workstation would be powerful enough to host such complicated simulations – but they would also be too expensive. 3M workstations from companies like Sun, IBM, and Apollo cost well over $25,000, and it seemed unlikely they would become affordable anytime soon, at least not to use for lower-level biology classes.

Jobs, in a heated monologue, declared that he would create a workstation as easy to use as a Macintosh, as powerful as a 3M, and at a cost no more than $500. Essentially, Jobs had promised Berg a NeXT-developed BigMac.

Lawsuit

NeXT still didn’t have a business plan or concrete plans for its first product. This would prove fortuitous for NeXT, because on November 4th, Apple filed suit. Apple’s case was based on NeXT’s raiding of senior Macintosh executives and conspiring to use the confidential knowledge Jobs and the others had about upcoming Apple projects (like BigMac).

Fortunately for NeXT, Apple’s hubris was on display. Apple failed to list any specific trade secrets that NeXT had violated, which violated a new law in California.

A week later, Apple came back with a list of twenty complaints but failed to demonstrate how NeXT had any “nefarious” (a term that was used extensively throughout Apple’s documents) plans against Apple.

The case proved to be a major embarrassment for Apple. All it did was get NeXT’s name in the news and show that Apple was deathly afraid of whatever products the company might produce.

Sculley was still trying to turn Apple around and get the Macintosh into businesses and homes. The lawsuit served as an embarrassing distraction from a resurgent Apple.

Sculley directed Apple’s legal team to settle with NeXT. In order to save face, Apple made NeXT agree to two conditions. First, NeXT would not release any products that competed with an Apple product released before 1985. Second, NeXT would have to show Apple all of its products before they were announced to the press so Apple would have the opportunity to file suit before the products got to consumers.

Building NeXT

Despite the lawsuit, Jobs began laying the groundwork for the perfect company. NeXT would be built to keep Jobs in control and improve his public image. This process began with a new logo, name, and office for NeXT.

Jobs had always had an eye for good design. He was especially taken with the logos of ABC, IBM, UPS, and Westinghouse, all of which were created by Yale professor Paul Rand. Rand offered to create NeXT’s logo for $100,000, but only if IBM consented.

![]() This was an outrageous price, many times more than what Rand had charged IBM for its now-iconic logo. Two months later, Rand sent Jobs a copy of the logo and a brochure explaining every detail. For the sake of a more interesting design, Rand even renamed the company NeXT, saying the ‘e’ stood for education. The new logo (and the name behind it) lent prestige and clout to a company without customers or a product.

This was an outrageous price, many times more than what Rand had charged IBM for its now-iconic logo. Two months later, Rand sent Jobs a copy of the logo and a brochure explaining every detail. For the sake of a more interesting design, Rand even renamed the company NeXT, saying the ‘e’ stood for education. The new logo (and the name behind it) lent prestige and clout to a company without customers or a product.

The office space didn’t fit the profile of a startup without any outside investors. Instead of cheap office space (a la Texaco Towers), Jobs chose some of the most expensive space in Silicon Valley. Named Deer Park (for the street it was on), the office space was outfitted with hardwood flooring and was decked out with lavish leather couches and Ansel Adams prints. Jobs eventually hired a full-time interior decorator for NeXT. The engineers and executives would all have desks on the second level.

The first floor of the office was dedicated to manufacturing. Instead of building a large factory, payroll, and stockpiles of parts, NeXT would buy preassembled components from outside companies, adopting the Japanese strategy of just in time manufacturing. The only manufacturing NeXT would do was assemble the finished components into computers, then ship them to resellers.

This made NeXT very flexible. It could change the number of computers it built very easily, making NeXT immune to shortages and surpluses that affected other companies (like Apple and the Lisa).

Communication was fostered by the layout of the offices. There were no closed office; everyone (even executives) worked at desks in a common area rimmed with conference rooms. Jobs led weekly “communication meetings” in the middle of the common area, where he briefed all employees on all facets of the company. Employees were even allowed to look at the company’s payroll to compare salaries (very few did).

Looking for a Product

For all the enlightened corporate policies, NeXT didn’t have a product. Jobs wanted NeXT to be in the higher education market, but he didn’t know just who he wanted to sell to. Would he create a personal workstation, inexpensive enough for individual students to buy, or a workstation for Paul Berg’s wet lab simulations that only the most well off universities could afford?

For the rest of 1985 and the first half of 1986, NeXT executives canvassed conventions like EduCom and talked to higher education buyers to find out what they wanted from a workstation.

The largest workstation vendor, Apollo, sold workstations that ran a proprietary operating system, Domain/OS, that was remarkably stable but very difficult to develop for. Also, there was no intuitive GUI for Domain/OS, meaning that undergraduates would almost never use the system. It would simply take too much time to train them.

Unlike Apollo or the upstart, Sun, which sent product managers and engineers to these conventions, NeXT sent Susan Barnes, its CFO, and the rest of the cofounders. Most buyers wanted a workstation that ran a variant of Unix, was easy to develop for, and was cheap enough to give to students to use as personal computers.

Such a system would cost around $1,000 and could be configured up if needed. The projected price point had already been bumped up with the addition of new features.

Development

Development began tentatively in January 1986. One of the earliest decisions was to have NeXTstep (the name Jobs had chosen for NeXT’s operating system) run on a microkernel. This meant that the operating system would be split into several different “servers” that ran independently of each other.

This had a couple advantages. First, if one server crashed, it could be restarted without restarting the entire operating system. Second, it meant that very little software dealt directly with the hardware, making the operating system very easy to move to different platforms.

Another major element of NeXTstep would be ease of development. Academic developers frequently wanted to recycle parts of programs. If there was a graphing utility in a spreadsheet, then it didn’t make sense to create a graphing utility for data gathering software.

NeXTstep would be completely object oriented. This meant that developers could reuse scraps of other programs very easily. Instead of writing a brand-new graphing utility, a programmer just had to make references to the existing software. This made for a much faster development process and more satisfying programs.

The hardware design for the NeXT computer was not particularly sophisticated, though it suffered from one major flaw. It used a standard processor from Motorola (the same line used in the Macintosh) and even featured two Apple Desktop Bus (ADB) connectors for the keyboard and mouse.

The one unique feature was the inclusion of a DSP (Digital Signal Processor). DSP’s accelerated sound processing. DSP’s were only featured in the highest end workstations and the computers that ran AT&T’s telephone network.

Instead of a hard drive to store users’ data, the NeXT computer used a magneto-optical disk drive, which was actually cheaper by the megabyte than hard drives. Data was stored on fat cartridges that kind of looked like DATs. The media was much less expensive than a hard drive, but it was very slow. Worse, the magneto-optical drive was the only removable media on the computer. This meant that a user couldn’t transfer files using a disk; everything would have to go through the network.

Just as with the Macintosh, Jobs devoted most of his attention to the user interface and physical design of the case, probably because he wasn’t a trained engineer. Jobs designed the Macintosh as a personal information appliance. The NeXT computer was an institutional information appliance. Instead of looking for a disarmingly cute design, Jobs wanted a computer that conveyed strength and power. He hired several different design houses to create prototypes.

The first company was based in London. It had gained notoriety for a design for a flashlight that had won an award. After a 16 hour flight and almost an hour of explanation, the company unveiled its design: a human head.

Jobs was disgusted. He ended up hiring frogdesign, a company started by the designer of the Snow White design language Apple would use in some form for almost a decade, Hartmut Esslinger.

The design that Esslinger had envisioned was unique. Unlike most other workstations, which were housed in boxy towers designed for ease of expansion and assembly rather than aesthetics, the NeXT computer was housed in a magnesium cube. The design was eye grabbing and effective. It allowed for a much smaller fan to cool the computer than a similarly outfitted tower, though it did take up more space on a desktop.

When frogdesign revealed the cube to Jobs, he immediately made the case the computer’s namesake: The NeXT computer was to be called the NeXTcube.

frogdesign also created a sophisticated monitor stand that tilted and raised the display with ease. The stand was so sophisticated that NeXT sought a patent for its design (which is very similar to the iMac G5 stand).

Unfortunately for NeXT, it became clear that the NeXTcube would feature too many custom components to implement the “just in time” plan Jobs had envisioned. NeXT moved some engineers to the first floor of the Deer Park office, and NeXT acquired a large warehouse in the working-class neighborhood of Fremont, near San Francisco Bay.

Jobs was obsessed with the user interface of NeXTstep. As a result, he spent most of his time hovering over the UI team. NeXT’s chief graphics designer, Susan Kare (who also created the icons and publications for the Macintosh), created the color scheme and widgets for the interface. Since the NeXTcube had a grayscale display and Display Postscript, Kare was able to create objects with depth while the rest of the world was still working with monochrome displays.

Some unique elements of the interface included the Dock (a combination application launcher, desktop, and task manager), draggable windows, and WYSIWYG editing. The printer and the display both used Postscript, so their output were consistent with each other.

Ross Perot

NeXT was burning through money. By late 1986, though NeXT was still far from shipping the Cube, it had used most of the initial $7 million investment Jobs had made.

Jobs could invest more of his own money, but that would look bad to potential customers. Jobs and his CFO, Susan Barnes, started making the rounds of venture capital firms, but nobody was interested.

Jobs was offering a 10% stake in the company for $3 million. That meant NeXT was worth $30 million, an outlandish figure considering that NeXT had no customers and no products – and wouldn’t for at least a few more years.

In 1987, after Jobs had nearly given up on finding an outside investor, NeXT had received an unexpected call from Ross Perot. Perot had founded IT giant, EDS, and had recently sold his company to GM.

Perot had seen the series The Innovators on PBS, which had featured a segment on NeXT. Jobs, Perot, and several executives met at the Fremont factory, which was still empty (supposedly because Jobs was unable to decide on a color scheme) and discussed Jobs’ vision for NeXT. Jobs charmed Perot into making the investment, except instead of a 10% stake for $3 million; Perot paid $20 million for 16%, valuing NeXT at $125 million.

After Perot signed the contract in the Fremont factory, he went to Deer Park and met the entire staff (more than a hundred people). One week later, Perot returned and greeted everyone by first name. This was radically different from Jobs, who lavished attention on the best and brightest at NeXT but rarely acknowledged the newer, less experienced staffers.

The gap in thinking between Jobs and Perot was huge, but Perot was too infatuated with Jobs to realize it.

Personal Life

As NeXT readied the NeXTcube for introduction, Jobs’ personal life was in flux. Jobs, who had been adopted, recently discovered his full sister, Mona Simpson, a famed novelist and writer. Simpson and Jobs became very close.

Simpson’s first novel, Anywhere but Here, was based on her experiences with an absentee father. The novel was a critical success, and Simpson became a celebrity in the literary world.

Unbeknownst to Jobs, Simpson began work on a second novel, A Regular Guy, which was based on Jobs and the development of the Macintosh. The novel revealed details about Jobs’ sex life and his first daughter that had not been known by the public. Simpson did change the names in her novel (Jobs was Tom Owens, Apple was Genesis, and Lisa was Jane), but the novel still hurt their relationship.

Jobs’ romantic life was tortured during the early years at NeXT. Since he still had his luxurious condo in near Central Park in Manhattan, Jobs went to several parties every year thrown by his tenants. At one of these parties, Jobs met Tina Redse, a graphics designer from California. Jobs was enchanted by her good looks. Redse and Jobs began an unsteady relationship. She moved in with Jobs for a while but left after a few months. The two stayed close for years to come.

In 1987, Jobs was invited to a party thrown by Washington Post publisher, Katherine Graham, in Georgetown. Famously, Jobs convinced King Juan Carlos of Spain into buying a personal computer.

Later that night, Jobs met John Akers, the CEO of IBM. Though the two men were fierce competitors (or at least would be once NeXT released the NeXTcube, which competed with the first RISC workstation in the world, the IBM RT/PC), Jobs was charming and kind. During their conversation, Jobs made references to the sophisticated NeXTstep.

Jobs didn’t think about the meeting again, but Akers pressed his executives to investigate NeXT and NeXTstep.

Prerelease

In 1985, NeXT executives had told university buyers that the NeXTcube would be released by 1987, but 1987 came and went. The slipping release date was partly due to the new features that were added during development and partly due to NeXT’s (Steve Jobs’) perfectionist attitude. Jobs spent months agonizing over NeXT’s patented monitor stand and even had the factory repainted when he didn’t like the shade of gray paint used.

Despite the delays, Jobs pushed ahead, refusing to pare back the NeXTcube’s specs. By 1988, there were 200 NeXT employees housed in two adjacent buildings. The growing campus was just as lavishly decorated as the original offices were. Jobs even commissioned a freestanding glass staircase to connect the first and second floor of the original Deer Park offices.

Ultimately, a prerelease version of the NeXTcube was made available to educators and students running beta NeXTstep in 1989 at US$6,500. This was well above the proposed $500 price point of 1985, making it too expensive for students to buy a NeXTcube to use as a personal computer. The base price included a NeXTcube, monitor, mouse, keyboard, and MO (magneto-optical) disk containing the operating system and a few add-on programs.

The software was all incredibly intuitive, but universities were willing to deal with the arcane UI’s of cheaper and faster workstations.

Instead of quietly releasing the prerelease NeXTcube to select customers, NeXT threw a lavish party to celebrate the event. The company rented the Davies Symphony Hall, supposedly because of its good acoustics, to show off the DSPs that allowed the Cube to play full stereo sound.

Jobs personally promised exclusive, behind the scenes access to the event to three publications. The editors found out about the other exclusives but put NeXT on the front page anyways.

The actual presentation was as meticulously planned as any Stevenote at Apple. Unlike any other Apple CEO, Jobs wrote his presentations himself, slaving over every slide and demo. The preparation showed, and the debut was a success.

The audience was wowed by the machine’s multimedia abilities. It played a duet with a violinist from the San Francisco Symphony, navigated electronic versions of Shakespeare’s plays, sent and received emails with embedded images and sounds, and showed off truly impressive graphics.

Release

Months after the debut at Davies Symphony Hall, NeXT released the final version of the NeXTcube, which retailed for US$10,000. Jobs and the senior executives made another grand tour looking for customers and developers. Most of the companies (like Disney and AT&T) remained solidly Macintosh, but Jobs charmed a couple big customers. NSA became a loyal NeXTstep user; so did Lotus (which agreed to develop an “object oriented spreadsheet”, Lotus for NeXTstep) and GM. Stanford and Carnegie Mellon both made small orders of NeXTcubes as well.

The outside world didn’t know about NeXT’s poor sales, since it was a privately held company. As a result, NeXT had a grossly disproportionate mindshare compared to its much larger competitor, Sun Microsystems. Even before the NeXTcube was released, retailers wanted to become official NeXT dealers, but Jobs wasn’t interested. He believed that the higher education market would be more than enough for NeXT.

When sales failed to materialize, NeXT made Businessland, a large office supply chain, a NeXT dealer. NeXTcubes would be offered in a few locations, and the NeXTcube’s successor would be featured nationwide.

More important than the displays in the stores was Businessland’s expanding sales team. Businessland’s sales team was already several times larger than NeXT’s, so it had valuable relationships with businesses. Even if an executive was not wowed by the NeXTcube’s pedigree or feature list, his or her relationship with the salesman might be enough for a sale.

Interestingly, NeXT replaced Compaq at Businessland, whose computers accounted for $150 million in sales. David Norman, a cofounder of Businessland, proclaimed that NeXT’s sales would top Compaq’s within a year.

Investors

The factory that Jobs had configured to produce 10,000 computers every month produced hundreds every month. Because of the low volume, human labor was cheaper than maintaining the automated equipment.

The business world didn’t know about NeXT’s disastrous sales, since NeXT was a private company. NeXT would go bankrupt if Jobs was unable to increase sales or find another investor. In order to appease Perot, Jobs sacrificed Lewin. The man, who had done so much to get NeXT considered in higher education, was out.

Jobs had invited universities to invest in NeXT. Carnegie Mellon and Stanford agreed and together invested $20 million. This would allow NeXT to operate for at least one more year.

NeXT’s true savior was Canon, the manufacturer of the Jobs-inspired Apple LaserWriter and the Hewlett Packard LaserJet. Jobs convinced Canon to invest $100 million in NeXT, a tremendous sum for a company with basically no sales and few prospects on the horizon. The truly shocking part was that Canon would only get 16.7% of the company, which meant that NeXT was now worth $560 million.

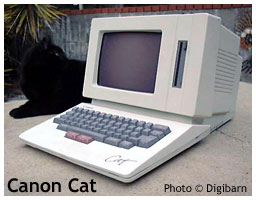

After the investment, Canon suspiciously canned Jef Raskin‘s Cat project, which was essentially a hyper-Macintosh Macintosh.

After the investment, Canon suspiciously canned Jef Raskin‘s Cat project, which was essentially a hyper-Macintosh Macintosh.

At the end of 1989, Jobs received excellent news. NeXT’s sales were still terrible, but IBM was now interested in licensing NeXTstep to use with its new line of personal computers – and perhaps even replace OS/2. His contact with Akers had finally paid off.

After about a month of negotiations and demonstrations, IBM agreed to pay $65 million to license NeXTstep indefinitely. When William Lowe (the first manager of the IBM PC group) showed Jobs a hundred page contract, Jobs threw it away. If IBM wanted to do business with NeXT, it would have to have a contract with fewer than five pages. Surprisingly, IBM complied.

NeXT was now flush with cash and ready to develop the successor to the NeXTcube.

Romance

After the well received NeXTcube launch, Jobs delivered a talk on entrepreneurialism to Stanford University. Jobs lost his train of thought halfway through the talk and wasn’t able to recover.

Jobs is renowned for his speaking abilities; he is usually poised and charming. He was fixated on a woman sitting in the front row, Laurene Powell, a Stanford Business School student. After the speech, Jobs got ready to leave for a business meeting. In a later interview, he said, “I was in the parking lot with the key in the car, and I though to myself, ‘If this is my last night on earth, would I rather spend it at a business meeting or with this woman?’ I ran across the parking lot [and] asked her if she’d have dinner with me.” (iCon 182)

In the weeks following, Jobs regaled his colleagues at NeXT about Powell. She was beautiful, vegetarian, smart, and had a good résumé to boot.

Powell had worked at Goldman Sachs before she entered Stanford Business School, where she told her roommate that she wanted to marry “a Silicon Valley millionaire like Steve Jobs” – Powell had decided on Jobs even before he set eyes on her.

The two started seeing each other regularly, creating a spectacle at both NeXT and Stanford. When Powell stayed overnight at the Jackling House, she would drive to classes in Jobs’ BMW with “NEXT” vanity plates. Jobs began eating lunch on campus at the Tressidor café. After classes ended at Stanford, Powell moved in with Jobs.

NeXTstation

Jobs was willing to compromise if it meant surviving. The new workstation from NeXT, the NeXTstation, addressed the Cube’s major shortcomings. It now had a floppy drive (allowing for file transfers without a hard drive or over ethernet) and a hard drive.

Jobs was willing to compromise if it meant surviving. The new workstation from NeXT, the NeXTstation, addressed the Cube’s major shortcomings. It now had a floppy drive (allowing for file transfers without a hard drive or over ethernet) and a hard drive.

Motorola’s newest processor, the 25 MHz 68040, was included. The processor would not be used in a Macintosh for more than a year. The computer was housed in a pizza box style enclosure, eschewing the Cube.

The major differences between the NeXTstation and the NeXTcube were color and distribution. Unlike the NeXTcube, the NeXTstation supported color, though a color display was an expensive option. This made the machine much more attractive as a multimedia workstation.

The NeXTcube was offered in a few college bookstores – and at less than a dozen Businessland locations. The NeXTstation was available in every Businessland in the country. On top of that, the NeXT sales staff was complemented by thousands of Businessland salespeople who were eager to earn commissions on the expensive workstation. The color version of the NeXTstation cost $7,995 ($975 less than the top of the line Macintosh IIfx, released the same year), and the monochrome version cost $4,995.

There was a typically Jobsian introduction for the NeXTstation. During a highly choreographed September 1991 press conference, Jobs’ staff had licensed the scene from Wizard of Oz where the black and white world of Kansas transforms into the colorful Oz. The scene played, and it stunned the audience. Nobody had ever seen full color, high resolution video on what was basically a high-end personal computer.

The demonstration was something of a fraud, however, since the video didn’t actually play on the computer. NeXT engineers had connected the machine to a LaserDisc player and simply used the NeXTstation as a display.

Even with a reduced price, enlarged distribution, and color graphics, the NeXTstation was a flop. NeXT managed to sell a few hundred every month through ComputerLand and had a couple big orders from the NSA and CERN, but not nearly enough to turn a profit. NeXT had already burned through most of the investors’ money, almost $247 million.

Marriage

As NeXT was burning through other people’s cash, Jobs’ personal life was in flux. In 1991, Powell found out that she was pregnant. Aside from Chris-Ann, a girlfriend Jobs had when he started Apple (who gave birth to Lisa, Jobs’ first daughter), Jobs had not been in any serious, long term relationship. After much hand wringing, he agreed to marry Powell, though he would not be a slave to tradition.

Instead of holding an opulent ceremony to appease the press, Jobs arranged to be wed at Yosemite National Park (a four hour drive from his Woodside home) by longtime friend and Buddhist monk, Chino Kobin. The guests were taken from the Jackling House to Yosemite on a large rented party bus.

Jobs had hired a Stanford professor to play guitar through the ceremony. In between guitar playing, gongs were hit and incense burned. After a brief ceremony, the two were married, and the party went on a wedding walk, not unlike the walks Jobs took with Sculley around Palo Alto and New York City.

Six months later, Laurene gave birth to Job’s first son, Reed Paul Jobs, named after Jobs alma mater (though Jobs had dropped out after his freshman year). Jobs abandoned the Jackling House (which fell into disrepair) and moved to a large home in old Palo Alto, near Andy Hertzfeld.

Saving NeXT

Jobs poured himself into the failing NeXT. He started going on more sales calls than ever before. This led to a few farcical and tragic incidents, but it didn’t result in a huge, NeXT-saving order.

From his years at Apple, Jobs had become a member of the American elite. He had an apartment occupying the top two floors of the San Remo, a twin towered building adjacent to Central Park. Other tenants included Rita Hayworth, Steven Spielberg, and Steve Martin. He rubbed elbow with the business elite from coast to coast.

When Jobs and a NeXT sales rep were in Detroit, Jobs stopped at Cadillac Place, the headquarters of General Motors, and asked to speak to Roger Smith, like Michael Moore had in his documentary, Roger & Me. The sales rep was shocked at the response – Jobs was ushered to the top floor, where Smith’s office was guarded by uniformed security and dogs. Smith came out and warmly greeted Jobs.

Pixar

Jobs tried to capitalize on his celebrity during a sales call with Disney, too. In 1991, Pixar and Disney were in the midst of discussions over a possible animated film. Jobs decided to pitch NeXTcubes and NeXTstations to Jeffrey Katzenberg, the head of Disney’s motion picture division.

Jobs launched into an unscripted speech on the merits of the two computers. Jobs passion got the better of him, and his speech veered into the possibilities of NeXTstep to foster an animation revolution, making it possible for everyone in America to produce their own animated films, without the help of studios like Disney (or Pixar).

Katzenberg said he might be interested in the monochrome NeXTcube, but in a cold voice he said, “I own animation, and nobody’s going to get it. It’s as if someone comes to date my daughter. I have a shotgun. If someone tries to take this away, I’ll blow his balls off.” (The Second Coming of Steve Jobs, 150)

Jobs was momentarily stunned by Katzenberg, but he resumed his presentation as if nothing had happened. Unfortunately for NeXT, Disney didn’t make any significant order of NeXTcubes or NeXTstations.

However, in the spring of 1991, Katzenberg agreed to produce a Pixar animated film.

Departures from NeXT

This was excellent news for Pixar, but NeXT was not so lucky. Jobs fired Lewin for the failure of the NeXTcube, and another cofounder, CFO Susan Barnes, left over the slow sales of the NeXTstation. Barnes, who was married to Bud Tribble, another cofounder, had concluded that NeXT was hopeless and took a position at Richard Blum and Associates in San Francisco.

When Barnes had given Jobs her month’s notice, he had her email and voicemail cut off before she got back to her office. Tribble followed suit. The next day, he tried to enter the office but found his security card was no longer valid. The same month, Businessland went belly up, ending NeXT’s only retail distribution.

After the high level resignations and Businessland closings, Canon got worried about their $100 million. NeXT was short of cash again, so Canon invested another $30 million to keep it going through 1991. Sales increased slightly, to almost 20,000 computers a year.

Another cofounder left in 1992, Rich Page, and sales failed to get better. Canon was forced to invest another $55 million in the company just to keep it solvent.

Saving NeXT

Morale at NeXT was terrible. Jobs himself considered resigning and handing control over to Canon, but he refused to admit that he couldn’t make another Macintosh. Weeks after Page left, three VPs resigned. During a staff meeting, Jobs tolled the remaining executives that “Everyone here can leave – except me.” (The Second Coming of Steve Jobs, 177)

Later in that meeting, it became clear that Theo Webgran’s (the head of NeXT’s European operations) sales staff was guilty of channel stuffing. Channel stuffing means selling more machines to retailers than they would ever be able to sell. NeXT was able to report the computers as sales, but retailers were stuck with unpopular, unsellable machines.

Jobs took radical steps to save NeXT – and his reputation. He announced to employees that NeXT would go public sometime in 1992 or 1993. Morale skyrocketed, since most employees had stock options that could possibly become quite valuable. News of the impending IPO got out, and pretty soon it was enjoying a wave of positive publicity. The newly motivated employees pressed harder for sales, since financial results, including detailed sales reports, would be publicly available information if NeXT was publicly held.

The first ever NeXTworld Expo was held on 1992.01.22. Among the minor hardware upgrades, it was revealed that NeXT would start shipping NeXTstep 486, a version of the operating system that would run on Intel hardware. The newly liberated software only took a few months to port, but it would have a huge impact on NeXT – and eventually on Apple as well.

Also announced was NeXTstep 3.0, which included better networking and file system compatibility with Windows and DOS.

Weeks later, Jobs dismissed Webgrans and most of the European staff. The headquarters in the French Riviera, which Jobs had only authorized because of the sales from channel stuffing, was closed. NeXT also cut off most of its dealers. The new management in Europe was unable to account for millions of dollars of NeXT inventory, but Jobs wouldn’t press criminal charges, because the negative publicity would kill his hopes of brining NeXT public.

Even counting the suspect sales in Europe, NeXT had sold only 8,000 computers and motherboards in 1992.

The most radical changes at NeXT had not yet come to pass. Jobs had prided himself in building an egalitarian company creating tools for educators and students. This strategy was untenable.

NeXT Software, Inc.

On 1993.02.08, InfoWorld ran a story claiming that NeXT was abandoning its hardware business. On Wednesday of the same week, Jobs confirmed the rumors: NeXT would become a software-only company, which meant new hardware partners and big layoffs. NeXT’s staff of 530 would be reduced to 200.

Jobs always thought of himself as a hardware designer. Though the public at large considered the Macintosh and NeXTcube groundbreaking software achievements, Jobs was much more involved in the hardware. Jobs spent weeks obsessing over the positioning of the floppy drive on the Macintosh or the shade of black used on the magnesium case of the NeXTcube. And now NeXT was essentially a startup software company with no product, no customers, and few prospects.

Without a factory, NeXT’s office space was its biggest expense. The company could no longer afford its Deer Park offices (it couldn’t afford them before, either). All of the extra computers and office furniture were auctioned off in September as NeXT moved to far more humble rented office space.

Half a dozen national periodicals ran exposés on Job’s erratic management style and the failure of NeXT. Dejected, Jobs began spending less and less time in the office, preferring to stay home with Reed and Laurene.

As NeXT settled into its new space, it released its first new software, NeXT for Intel Processors (renamed because it would also run on Pentium machines) for $995. The major difference between NeXTstep for Intel and NeXTstep 3.0 was utilities that allowed dual booting with Windows and limited file sharing between the operating systems.

Profits

Sales from NeXTstep for Intel made NeXT “consistently profitable”, according to Jobs, making at least $1 million in 1994 on $49 million of revenue. With the new money and success, NeXT began developing versions of NeXTstep to run on Windows and even the Internet. Though the Windows software would never make it past developer releases, the Internet version of NeXTstep, WebObjects, was very successful and eventually supplanted NeXTstep as NeXT’s biggest money maker.

WebObjects was an object oriented environment for the Internet. It allowed developers to create intelligent websites that were able to update themselves for individual customers. The software was most famously used by Dell as the basis of its online store, and it was also used by the BBC and Disney.

Sun Microsystems was beginning to feel the pinch from Windows NT. Workstation performance was now possible on ordinary PCs running Windows NT. Worse, the next generations of workstations with PowerPC or MIPS processors were all capable of running Windows NT.

Sun needed a competitive edge, and SunOS (renamed Solaris) was not providing it. NeXT and Sun reached an agreement for Sun to license the NeXTstep environment and port it to Solaris. This put several million dollars in the bank and made NeXT solvent for the next three years.

The new product was called OpenStep; it was available for Solaris and other Unix operating systems. The partnership was announced in late 1993, and NeXT released its version of OpenStep for Solaris in 1996, though Sun never incorporated it into Solaris as was first planned.

Personal Successes

As NeXT recovered, Jobs’ personal life thrived. His other company, Pixar, was gearing up for the wildly successful Toy Story release, and an IPO that would make Jobs a billionaire.

Laurene was pregnant again in 1994, and Jobs’ first daughter, Lisa Brennan-Jobs, started her freshman year at Harvard.

Apple?

Jobs had never given up on the idea of returning to Apple. As Michael Spindler, the successor to John Sculley, stumbled, Jobs visited the headquarters of National Semiconductors to talk to Apple’s newest board-member, Gil Amelio. He told Amelio, “There’s only one person who can rally the Apple troops, only one person who can straighten out the company.” That person was Jobs.

Jobs wanted to enlist the support of Amelio in a possible coup against Spindler at the upcoming shareholder’s meeting (Jobs was still entitled to attend, since he still owned one Apple share). Amelio was taken aback by the discussion and quickly forgot about it.

By early 1996, Apple was struggling to create a brand new operating system to replace increasingly unstable Mac OS. Efforts had begun even before Jobs left (such as the BigMac project), but all had failed.

Apple’s most recent – and least ambitious – attempt to create a modern operating system to compete with the looming threat of Windows NT for Consumers (a product which would be released as Windows XP five years behind schedule) was named Copland and wasn’t making much progress. In order to make Copland compatible with existing Mac OS applications, there would be very few changes to the underlying Mac OS code. The biggest change would be its new nanokernel and networking capabilities.

Changing Direction

After spending hundreds of millions of dollars on Copland, Gil Amelio (Apple’s new CEO of less than a hundred days) decided that the software would never be ready for release and directed his CTO, Ellen Hancock, to make a list of possible outside operating systems to to license or buy outright.

The most obvious choice would be to buy the fledgling Be Inc., which was founded by former Apple executive, Jean Louis Gassée, and was working on BeOS, which was available to the public through developer releases. BeOS was incredibly fast, and it was built on a microkernel, just as NeXTstep was.

Unfortunately, BeOS was still buggy, and worse, it had almost no outside developers or customers. Still, buying BeOS would have been better than licensing Solaris or Windows NT, and relying on outside companies for Apple’s most important asset.

Gassée sensed that BeOS was the first choice of Apple and was very cocky in his negotiations.

Gassée offered to sell Be to Apple for $200 million and lead the new division himself. Amelio was put off by the price, especially after Apple’s legal team valued Be at no more than $50 million.

Still, Be was the best that Apple could afford, for now.

Out of the Blue

Out of the blue, Jobs called Amelio shortly before Thanksgiving and urged him, for Apple’s sake, to steer clear of Gassée. A month later, a NeXT sales rep, Garret L. Rice -supposedly acting on his own volition – suggested that Apple consider NeXTstep, which was in the process of being ported to PowerPC, to one of Hancock’s staffers.

Hancock began to research NeXT, which by now had several developers and hardware partners – and, most importantly, two finished operating systems, OpenStep and NeXTstep.

On 1996.12.02, Jobs met with Amelio and Hancock on the Apple campus and discussed Apple’s future. Jobs gave a demo of NeXTstep and explained how object oriented programming could revitalize Apple’s developers and attract enterprise customers to the Mac.

Seven days later, NeXT engineers began meeting with Apple engineers to discuss how a Mac OS-NeXTstep transition would work and how to preserve Mac OS compatibility.

On 1996.12.20, Amelio announced to the public that Apple would buy NeXT for the price of $427 million and would base the next version of the Mac OS on NeXTstep.

Jobs returned to Apple as an advisor to help with the transition. It was the first time Jobs had been at the Apple campus in almost eleven years.

This article was originally published on 2006.12.20.

Further Reading

- Good-bye Woz and Jobs: How the First Apple Era Ended in 1985, Orchard

- NeXT, OpenStep, and the Triumphant Return of Steve Jobs, Orchard

- Full Circle: A Brief History of NeXT, Orchard

- The Pixar Story: Dick Shoup, Alex Schure, George Lucas, Steve Jobs, and Disney, Orchard

- BigMac, L’Aventure Apple (French)

- Snow White design language, Land Snail

- NeXTstation, Slashdot

- Copland, BusinessWeek

keyword: nextyears