Ever bought a piece of software back in the day that made you go Wow!? Not being able to wait to open it? Just sensing true greatness lying within the box? Something on that disk you knew without a doubt you’d never forget?

Old timers, get ready for a time warp here – and even young squirts like myself will remember this one.

Remember the squadron of Flying Toasters flying across your computer screen? Aquatic Realm, anyone? How ’bout Starry Night to light up the night?

Remember the squadron of Flying Toasters flying across your computer screen? Aquatic Realm, anyone? How ’bout Starry Night to light up the night?

Yep, I see that grin on your face! Those were only a few of the wonderful modules that were a part of the unforgettable screen saver known as After Dark.

After Dark will forever be remembered as the screen saver that got the screen saving boom started in the 90s. Through the artistic foresight and the engineering spirit of two people, Jack Eastman and Patrick Beard, After Dark was born.

After Dark will forever be remembered as the screen saver that got the screen saving boom started in the 90s. Through the artistic foresight and the engineering spirit of two people, Jack Eastman and Patrick Beard, After Dark was born.

It started life on the Macintosh. Later, Berkeley Systems, the publisher of After Dark, along with Jack Eastman and Patrick Beard, would team up with Bill Stewart and Ian MacDonald at Software Dynamics. Through this collaboration, After Dark for Windows was born. (Stewart and MacDonald were the creators of the Magic screen saver, which was the first screen saver for Windows. For a more in-depth history of Magic as well as After Dark, check out the Software Dynamics website.)

The Birth of After Dark

The year was 1994. While I was still in the PC world, my first experience with a screen saver was with After Dark 2.0. I still have fond memories of that day – a relative of mine gave me a piece of software known as a “screen saver”, which I had never heard of. I checked out the box and got this feeling, “This is gonna be cool!”

Digging through the box, I found the installation floppy neatly placed in its envelope. After more looking, I spotted the manual as I started about the process of installing After Dark. Once installed, I was in complete awe of each and every module. With eyes glued to the screen, I stayed up late into the night watching in awe as the artwork and images flooded the screen and my memory.

From that point on, I was a devoted After Dark fan. Three of After Dark’s biggest draws were:

- Roll Your Own Modules: Anyone could try their hand at creating their own modules. Berkeley Systems even held contests annually for the best module. Some of those same modules found their way into future versions of After Dark. This inspired more creativity, which in turn led to finding more talented artists in the screen saver genre.

- Randomizer: Ever get tired of clicking on each individual module? Or perhaps you’re one of those who likes to shuck and jive things up? A little pizzazz if ya will… Instead of selecting each module to run manually, you could add as many to the Randomizer as you wished. A slider bar would let you select the interval of time each module would be displayed before moving onto the next. You could have the modules follow in order or at random. You could even have multiple Randomizers. An example of this would be in one Randomizer, you could have all the After Dark 2.0 modules and in another you could have all the Star Trek models just to keep things all nice and tidy!

- MultiModule: Whadda ya get when you take two or more of your favorite modules and throw ’em all together? MultiModule of course! The idea here was to take two or more modules and combine them into one to create even more awe and bewilderment. One example is Toasters in Space. Did ya ever wonder how’d they do that? Take one part Flying Toasters, another part Warp and Voila! Toasters in Space!

More versions would follow. My next purchase was More After Dark, which added 25 more modules to After Dark 2.0.

There were other screen savers that carried the proud lineage of the After Dark name and tradition, which continued to capture imaginations, such as Disney, Star Trek, The Simpsons, Marvel Comics, Looney Toons, and Totally Twisted. In addition to Macintosh and Windows versions, there was also a standalone DOS version. I moved up to 3.0, then to 4.0. Unfortunately, 4.0 was the last major version of After Dark.

There were other screen savers that carried the proud lineage of the After Dark name and tradition, which continued to capture imaginations, such as Disney, Star Trek, The Simpsons, Marvel Comics, Looney Toons, and Totally Twisted. In addition to Macintosh and Windows versions, there was also a standalone DOS version. I moved up to 3.0, then to 4.0. Unfortunately, 4.0 was the last major version of After Dark.

With the advent and popularity of free screen savers, along with the boom of the Internet, After Dark’s star eventually burned out. Berkeley Systems would eventually fade into obscurity when it was bought out by Sierra. Sierra would go on to release After Dark Games, which were wonderful, not to mention fun games based on the After Dark screen saver.

Although no newer After Dark versions would see the light of day, Sierra would repackage the major versions under different names: After Dark Classic, After Dark Deluxe, and After Dark Midnight Edition, to name a few. Eventually After Dark saw its end as far as Sierra was concerned in the early 00s.

As part of this tribute to After Dark, I recently interviewed Jack Eastman and Patrick Beard, who created After Dark, along with Bill Stewart, who worked with Jack and Patrick to port it to Windows. Be sure to come back for my interviews with Patrick Beard and with Bill Stewart. This is my interview with Jack Eastman.

Tommy: It’s quite an honor to interview you. How did After Dark see the light of day? What was the inspiration behind it?

Jack: I actually never intended it to see the light of day. It was a personal project. I was working on my Ph.D. thesis project at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. I taught myself to program the Macintosh during that time.

It was fun and exciting to work with the Mac in those days – I’m talking about 1986. I had learned Pascal in college at UCSD in probably 1981. I wanted to do some graphics programming on the Mac – most of my programming before that was done on machines that didn’t support great onscreen graphics. Teraks at UCSD, Commodore PET and VAX at Berkeley. Scientific American had some articles about graphics algorithms for fun things like expanding ripples on water. Just line-drawing stuff. I wanted to try those on the Mac. I did one or two, and it occurred to me that it would be fun to have them as a screen saver.

As I started to dig in, I found that it was much, much harder to write a screen saver than to do the graphics. So my idea was, let’s solve the screen saver problem once, then have the graphics be modular – build the TV and then change the channel.

As I dug in to systems programming on the Mac, it became really hard. There was no concept in the OS of a screen saver, so I had to hack everything. A friend of mine at LBL, Patrick Beard, helped me figure some things out. He was a programmer for the Astrophysics group down the hall.

Anyway, I decided the best way to get close to the iron on the Mac was to do it in assembly language. It was the only way to hack the OS calls in those days. I had to patch OS calls to notice periods of inactivity, stay on top of all windows, notice the mouse moving, and so forth. At some point I had something working, and I gave a copy to Patrick. By that time he was working at Berkeley Systems – working on Mac utilities.

Berkeley Systems had a virtual screen program for Mac – you could move the mouse to an edge of the screen and push and see more screen there. Great tool on a 9″ screen. Also a screen magnifier for low vision

Patrick was working on a network-based application-sharing program – way ahead of its time.

Tommy: I heard about the screen magnifier at some point.

Jack: inLarge it was called. The virtual-screen program was Stepping Out.

Tommy: I’ve heard of that.

Jack: Anyway, I gave him that early version of After Dark (it had no name at that point), and he ran it at work. At some point the boss walked by and saw a fun screen saver on Pat’s screen and later, saw another. He asked what it was – Patrick put him in touch with me. We did a deal where I agreed to finish it up – do what was needed to bring it to market. Wes Boyd was the boss. He thought we’d sell a few units – a niche product like Stepping Out. But it caught on and scared us all.

Tommy: Ha ha! Big!

Jack: Yeah, big. We decided we had to professionalize quick. Wes’ insight was that we needed to bring artistry to it. 1.0 was all line-art stuff: water ripples, worms crawling around the screen, rainfall, stars.

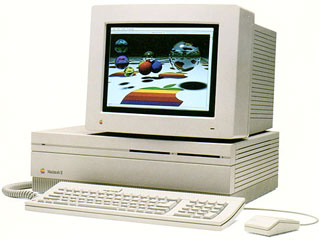

For 2.0 we needed to build more personality into it – really engage. We thought this over in the abstract for quite a while. My wife’s a doctor – she was doing her residency then and was frequently gone overnight. So I’d sit up late programming. Very late. I had a Mac II with a color screen – $5,000 computer in those days.

For 2.0 we needed to build more personality into it – really engage. We thought this over in the abstract for quite a while. My wife’s a doctor – she was doing her residency then and was frequently gone overnight. So I’d sit up late programming. Very late. I had a Mac II with a color screen – $5,000 computer in those days.

One of those late nights I was thinking about the artistry problem – how to do something really fun for 2.0. I was wandering around the house. I drifted into the kitchen, and the toaster caught my eye. My sleep-deprived brain put wings on it.

I went upstairs and drew some animation frames – I used the development system’s icon editor. Little white outline toasters on a black background with little stubby plucked-chicken wings speed lines and a flapping electrical cord. I coded up the animation that night and brought it to Berkeley Systems the next day. Everybody thought it was hilarious and everybody agreed it needed to be redrawn.

Wes brought in an artist to re-render the toasters, and Patrick re-coded the module in C. The modules all had a little control panel – I insisted on having a slider that controlled the doneness of the toast.

Wes brought in an artist to re-render the toasters, and Patrick re-coded the module in C. The modules all had a little control panel – I insisted on having a slider that controlled the doneness of the toast.

The other thing we were careful to do was not to put the toasters on a track and repeat the show. Random numbers were always important from that point on. I had done Monte Carlo simulations in my physics work and knew how to produce random numbers in various distributions. I think that was an important idea – we had these little movies, but you couldn’t predict them.

Competitors didn’t have that insight. With After Dark you could just zone out and watch for a long time. Plus it was really a screen saver – it wouldn’t do to have images sitting in one place or in repeating patterns.

Tommy: I definitely concur with that. I’m still in awe of After Dark to this day. I can watch it for hours on end and never get tired of it.

How did After Dark 2.0 differ from 1.0 overall?

Jack: Miles of difference. The difference between an engineer and an artist.

Tommy: Let me dig a little deeper here. What did 1.0 include module-wise, and did it ever ship in a retail box like 2.0 did?

Jack: Oh yes, it was boxed. Shipped on floppies. Included raindrops, Starry Night, worms. I don’t remember all of them, but there was not a single bitmapped image. Everything was lines and circles. Big hit nevertheless.

Tommy: The reason I ask this is because everyone always talks about 2.0 and later versions. I personally have never seen 1.0 myself.

Jack: Well, 2.0 was really the breakout. We had learned a lot technically, artistically, and in terms of marketing. The box was a lot more attractive, the engine more stable and played better with others, and it featured Toasters and Fish.

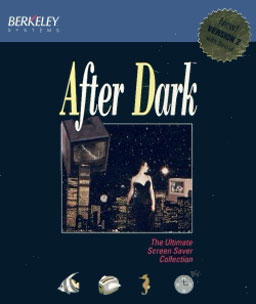

Tommy: Part of the After Dark experience was when I first saw the box. It screamed “darkness”. I just knew that I would enjoy it from the time I first looked at the box. Even the installation program had a great sense of humor.

Other than you and Patrick, who were the other creative forces behind After Dark?

Jack: Well, Nick Rush, who was VP of Marketing, had a lot of great input. And later, Igor Gasowski built a very strong design department and was a huge creative influence. Wes’ wife, Joan Blades, did the first box cover art, which I always thought was great.

Tommy: Tell me how Bill Stewart and Ian MacDonald came into the picture, thus leading to the Windows port of After Dark?

Jack: Well, at some point in the early 90s it became clear that Windows was real and would challenge the Mac. Nobody in the company knew anything about it. So I think it was Wes who cast around and found these guys.

Tommy: What was it like collaborating with Bill and Ian?

Jack: They had their own world. We were wary of Windows and just feeling like we had really conquered the Mac, both technically and in marketing terms. They were the prophets of a new religion. We were uncomfortable, because we couldn’t evaluate what they were doing very well – being totally ignorant of the new platform. Ultimately they did a fantastic job.

Tommy: In my mind, After Dark 2.0 had a “darkness”, a sense of the modules actually portraying the idea of “After Dark”, through many of the modules such as Nocturns, Zot, Starry Night as well as others. Was this how you envisioned After Dark and the latter versions to follow both 1.0 and 2.0?

Jack: Yes. In those early days we took the screen-saving very seriously (later CRTs had phosphors that were much longer-lasting). So it translated into a dark artistic outlook.

Tommy: I have several compact Macs as well as PCs running After Dark, and especially during Halloween, I’ll turn on After Dark and put a compact Mac in each window so others can see!

Jack: Ha!

Tommy: Do you feel the direction and the creativity behind After Dark changed after 2.0 – and if so, in what way?

Jack: I’ve always been proud that the Berkeley Systems team remained very strong creatively over a sustained period. We built some great tools for collaboration between engineers and artists that let artists author experiences that we could then code up in a randomized and modular way. I think we had one of the strongest cross-disciplinary collaborations of any studio in those days. Even when we did licensed products like Disney and Star Trek, there was huge creativity coming out of our shop.

Tommy: Did the versions following 2.0 and More After Dark stray from the “darkness” aspect in your opinion?

Jack: Well, it became less technically important to have the screen be substantially black, so we relaxed some of those guidelines and let the creative juices flow more freely.

Tommy: In your mind, were 3.0 and later versions better or worse in terms of creativity than 2.0. Did they turn out how you had hoped they would?

Jack: Oh, I think there’s no question that we grew creatively. The team grew physically in size, so many more voices were heard. Engineers as well as artists contributed creatively. So I think by the time we did 4.0 and Sick and Twisted and so forth the creativity was really rich. I think there’s an enduring charm about some of the 2.0 stuff – but we tried to make sure that stuff was always part of the mix, too.

I articulated it at one point: Our philosophy was to remain “aggressively stupid”. Even my old toaster art got resurrected as ProtoToasters in 4.0, I think.

Tommy: How long did you remain a part of the After Dark team?

Jack: How long was I involved? I started working on my own in about 1986. I graduated (against all odds) in 1990 – and immediately joined Berkeley Systems as VP Engineering. I stayed with the company for a while after its sale but left in 1998. I wanted to flex my engineering muscles a little at that point – I’d been in management for a long time – so I worked on After Dark Games as a consultant. I was sort of Alpha Geek for that project.

Then I did my obligatory Internet startup company, which lasted four years. Now I’m consulting again. I love working out of my attic. I’m playing Puccini’s “Turandot” at high volume now.

Tommy: After Dark was and still is my all-time favorite program. I was deeply saddened when After Dark was finally “laid to rest”, so to speak. I continued supporting After Dark and its subsequent versions.

How did you feel when you learned there would not be an After Dark 5.0? Were there ever plans for a 5.0?

Jack: We never had plans that I recall. The bloom was off the whole screen saver market by late 1990s. Harder to justify new versions. But we had a big hit in “You Don’t Know Jack”, and we were trying hard to figure out how to do new things on the Internet.

Well, the economics really changed. The company was sold and sold again, and the studio finally shut down. There’s nobody doing really creative screen savers these days, that I know of.

Tommy: That’s a shame, too!

Jack: The good news is that there’s huge creativity in the game sector.

The game studios are doing well now – though it’s becoming more like Hollywood in scale. But if you want to see some of the old After Dark charm, check out something like Wii Sports.

Tommy: Have you personally ever considered releasing another screen saver in the spirit of After Dark? A 5.0 if you will.

Jack: Naw. I admit it would be fun! But I’ve got other creative and technical interests now, and the market’s no longer there. Mainly from a technical standpoint: I feel like I’ve solved that problem already and I want to spend my time on other challenges.

Tommy: In your mind, what was the defining feature or part of After Dark that made it unique?

Jack: Charm; creativity; non-repetitiveness; stupidity.

Tommy: What’s your favorite module of all time?

Jack: After all this – still gotta be those toasters, man.

Tommy: What do you want those who read this article to know about After Dark they may not know already?

Jack: I guess that we never saw it coming. We were just having fun – we had no clue that it would catch on like that!

Tommy: Hey Jack, I wanna thank you again for this interview. It was truly a blast to be able to hear from you. I’ll never forget After Dark.

Jack: Happy to oblige!

Come back for my interview with Patrick Beard, who worked alongside Jack in creating After Dark!

Go to the After Dark Interviews index.

Keywords: #afterdark #screensaver

Short link: http://goo.gl/cgPMji

searchword: afterdark