John Sculley, who had once been hailed as Apple’s savior for huge sales increases and good PR (like Bill Gates, Larry Ellison, and Steve Jobs rolled in one) had presided over the splintering of the product line and a sharp decline in market share. The same trends continued after Sculley was forced out, and the former leader of the international Apple subsidiaries and COO, Michael Spindler, took control of the executive suite at Apple. Under Spindler’s leadership, Apple remained in a state of decline.

After the release of the well received Power Macintosh in 1993, market share continued to slip. The only solution, it seemed, was to either sell the company or find an outside manufacturer with credentials in the business market to help bolster the Mac’s market share.

After the release of the well received Power Macintosh in 1993, market share continued to slip. The only solution, it seemed, was to either sell the company or find an outside manufacturer with credentials in the business market to help bolster the Mac’s market share.

During Sculley’s reign, Apple was in the final stages of being acquired by Sun Microsystems. Negotiations stalled after Scott McNeally, Sun’s CEO, stipulated that he would become the COO of a new Apple, displacing Spindler.

RISC Projects

Shortly after the Sun deal fell through, the RISC projects at Apple came to an apex. After early attempts to design a RISC processor on its own, Apple turned to its longtime partner, Motorola. Since the mid-80s, Motorola had been working on a successor to the 680×0 line, the 88000. Incorporating the research of John Cocke at the Thomas Watson Research Center, an IBM lab, the 88000 was a RISC design, meaning that it included far fewer operations than an ordinary processor, and those operations were heavily optimized. The missing functions were then implemented in software. (IBM would later release its own RISC workstation, the RT/PC.)

Work on the 88000 workstation at Apple was going slowly, and it had no capacity to run existing Mac OS software.

Teaming Up with IBM

Another project was started up to create a workstation capable of running existing Mac programs. After changing processors several times (the SPARC was the popular choice amongst the engineers), the team decided to use the POWER processor from IBM. Talks to use the processor eventually evolved into merger negotiations.

Sculley was eager to recruit another company to help market the Mac, especially with the growing popularity of Windows and OS/2.

The merger came close to completion; both companies had drafted press releases announcing the deal. One major hiccup appeared: The merger would take place in the course of a year, so IBM wanted a head start on creating IBM-branded Macs in order to test the market for business Macs. IBM would not sign the agreement unless Apple would allow IBM to sell Mac OS computers for a trial period. If the machines succeeded, IBM would continue with the deal. If not, the merger would be off.

Sculley always balked at licensing the Macintosh to other companies. Apple lost a good deal of revenue to competing Apple II cloners, such as Franklin, which all used illegally copied ROMs, so Sculley was nervous about inviting other companies to compete with Apple in the hardware market.

Bill Gates had urged Sculley to license the Macintosh OS to other computer manufacturers shortly after its launch in 1984, but Sculley refused and was not interested in reversing his position because of IBM. As a result, the deal fell apart, and Apple no longer was IBM’s acquisition target. Instead, Apple became a strategic partner in the alliance that produced the PowerPC processor.

The first products that emerged from IBM’s labs were CHRP (Common Hardware Reference Platform) motherboards, the platform that would power the Macintosh and every other PowerPC-based computer from IBM and any other manufacturer. This standard would later evolve into PReP (PowerPC Reference Platform) and would become (as Apple then thought) the key to the clone market.

‘No’ from Compaq and Gateway

Sculley’s fortune changed. By 1993, the board had become dissatisfied with Apple’s dropping market share and forced Sculley out, allowing him to preside over the release of the Newton before he left. His heir presumptive, Jean Louis Gassée, had left the company earlier in 1992. That meant that Michael Spindler, COO and former head of the German Apple subsidiary, was next in line for CEO.

He assumed the position and almost immediately began trying to seek out a major computer manufacturer to sell branded Macintoshes. The only companies to express interest in selling the Macintosh, Gateway 2000 and Compaq, were pressured by Microsoft to not sell the Macintosh clones, which would be in direct competition with Windows.

Spindler desperately wanted one of the established computer manufacturers to be the first to market a Macintosh clone. That would lend credibility to Apple’s efforts in the business market. After the deals with Compaq and Gateway 2000 failed, Spindler had no choice and was forced to license the software to smaller companies – or not at all.

Power Computing

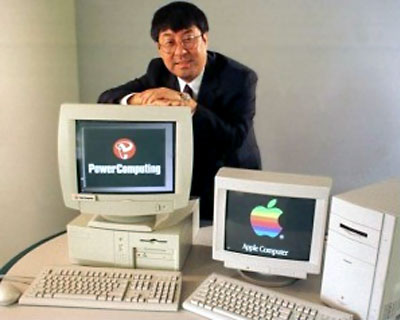

Steve Kahng, one of the key executives at Daewoo’s PC division during its meteoric rise in the mid-80s, wanted to do the same thing for the PowerPC in the 90s. Kahng had failed to profit from Daewoo’s PC division (Wall Street Journal writer, Jim Carlton, has stated that he could have made as much as $50 million), so he would have to get a partner. Elsireno Piol, a senior executive at the Italian computer giant Olivetti, arranged a meeting through a mutual friend with Kahng to talk about the PowerPC.

Piol viewed the PowerPC as the key to ending Microsoft’s and Intel’s dominance in the computer industry, and he wanted to set up a US-based, Olivetti-backed firm to create a PowerPC computer. Olivetti would put up $4 million, and Kahng would have to put up the remaining $5 million (mostly from his savings from being a successful consultant). The new venture was named Power Computing.

It was initially thought that the Macintosh would not lead the PowerPC revolution. Instead, most believed that OS/2 would take hold on the platform and flourish. But IBM dragged its feet on releasing an OS/2 version for PowerPC and failed to market it effectively. No manufacturers were interested in the operating system, even though it was more advanced than the x86 version of OS/2 and Windows, since it could compromise their relationships with Microsoft. As a result, the Mac OS became the standard-bearer for the platform, and Kahng would only settle for it.

In April 1994 (months after the Power Macintosh first appeared on the market), Apple had set up its licensing office to help convince other manufacturers to sell Mac clones. Amongst all the heady negotiations, the office found time to produce a satirical video, I Think We’re a Clone Now, which by that time had become an Apple tradition.

Its negotiations with larger, entrenched companies had failed, yet Apple was still unwilling to speak to smaller companies. Steve Kahng attempted to begin working with Apple but was rebuffed because of Power Computing’s stature in the computer industry. Eventually, Kahng had Olivetti request the needed information, and then Apple divulged it.

In June 1994, Kahng met with the head of the licensing office, Russ Irwin. Irwin agreed to give Power Computing access to the specifications of the Power Macintosh that he needed to produce a fully compatible clone. In the meantime, Power Computing had made a number of important hires, Carl Hewitt and Gary Davidian from the PDM group at Apple that had produced the Power Macintosh and its software.

After Power Computing was giving the necessary information, work progressed quickly. The first functional prototypes were completed in October 1994. The prototypes were housed in standard ATX towers, used standard VGA monitors along with PS/2 mice and keyboards, but ran the Mac OS. The prototypes made their debut at the Comdex show in November 1994 at the Motorola and IBM booths. They were the talk of the Mac crowd, and Apple was pressured to make Power Computing the first Macintosh licensee. The final paperwork was signed in December of 1994 by Spindler and Kahng. The deal was announced on December 27, 1994.

After Power Computing was giving the necessary information, work progressed quickly. The first functional prototypes were completed in October 1994. The prototypes were housed in standard ATX towers, used standard VGA monitors along with PS/2 mice and keyboards, but ran the Mac OS. The prototypes made their debut at the Comdex show in November 1994 at the Motorola and IBM booths. They were the talk of the Mac crowd, and Apple was pressured to make Power Computing the first Macintosh licensee. The final paperwork was signed in December of 1994 by Spindler and Kahng. The deal was announced on December 27, 1994.

Kahng had to move fast to secure a place in the market for his clone. A Macintosh peripheral company, Radius, had been granted a license just days later (which it would later license to the scanning giant, Umax), and Motorola also had a clone in the works.

Famously frugal, Kahng made a number of decisions about Power Computing that would propel it to the foreground of the computer industry in general. First, like the incredibly successful Gateway 2000 and Dell, Power Computing would sell its computers exclusively by mail order, eliminating the need for retail partners (and the reduced profit margins they demanded). Second, Power Computing would not build its own factory. Instead, the company rented space from the flagging CompuAdd, a PC clone manufacturer that had seen its peak in 1991.

In May 1995, the Power 80, the first Macintosh clone ever legally sold, was made available to the public. The computer was met with rave reviews. Not only did the computer outperform its Apple counterpart, but it was much less expensive (Apple required only a 7.25% royalty for the Mac OS, less than what Microsoft got in the x86 world).

In May 1995, the Power 80, the first Macintosh clone ever legally sold, was made available to the public. The computer was met with rave reviews. Not only did the computer outperform its Apple counterpart, but it was much less expensive (Apple required only a 7.25% royalty for the Mac OS, less than what Microsoft got in the x86 world).

By the end of 1995, Power Computing had sold over 50,000 Macintosh clones and generated $100 million in sales. Spindler and the rest of the executive team resented their success. Its profits and sales were not coming from new customers; they believed that most Power Computing customers were former Apple customers attracted by lower prices and better performance.

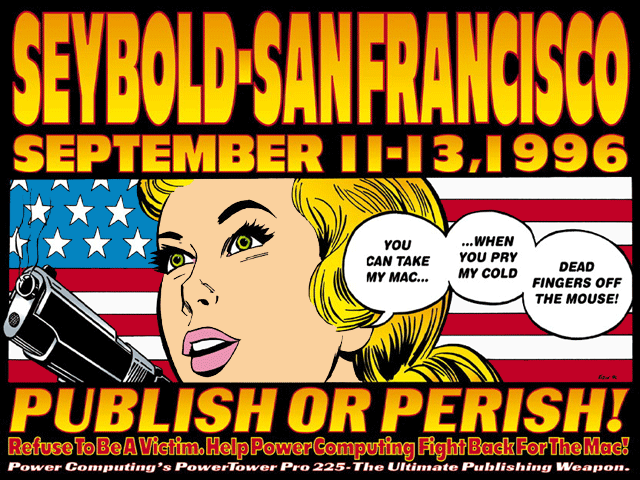

“You can take my Mac when you pry my cold, dead fingers off the mouse!”

Power Computing launched an incredibly popular advertising campaign promoting its new computers. Unlike Apple’s ads, which were fairly non-confrontational, Power Computing’s ads were very aggressive. The most famous (and controversial) ad featured Sluggo, the comic strip character, punching an effigy of Bill Gates with the caption “Let’s kick Wintel’s ass!”

Power Computing launched an incredibly popular advertising campaign promoting its new computers. Unlike Apple’s ads, which were fairly non-confrontational, Power Computing’s ads were very aggressive. The most famous (and controversial) ad featured Sluggo, the comic strip character, punching an effigy of Bill Gates with the caption “Let’s kick Wintel’s ass!”

The company would land in hot water for the ad, eventually being sued by the comic strip’s owner for copyright violation (Power Computing had failed to secure permission to run the ad).

The End of Power Computing

Two years later, relations with Apple had degraded seriously. Power Computing was a media darling, while Apple was struggling to regain credibility in the midst of the failed Copland project. In a much publicized coup, Gil Amelio had assumed control of the company from Spindler. Relations were positively frigid.

Power Computing, cognizant of Amelio’s attitude toward the clones, attempted to avoid keeping all its eggs in Apple’s basket. It began to actively support Jean Louis Gassée’s BeOS. Be’s first public demonstrations were on Power 120’s (upgraded versions of the Power 80), and Power Computing began selling machines outfitted with BeOS out of the box, thus bypassing Apple’s 7.25% royalty.

Unfortunately, when Gil Amelio made the decision that Apple would buy NeXT for its OpenStep operating system, he instigated a series of events that would place Steve Jobs at the helm of the company. Jobs promptly revoked the later clone manufacturer’s licenses (their contracts stipulated that they could be terminated at Apple’s discretion), but Power Computing was different. To close the company’s cloning business, Apple spent $100 million to acquire Power Computing’s cloning business.

Power Computing went on to start a short lived venture in the x86 clone market but was sued by suppliers for unfulfilled orders and went out of business in 1997.

Keywords: #powercomputing #stevekahng #macclones

Short link: http://goo.gl/Lf22OQ

searchword: powercomputing