Steve Jobs’ career at Apple was unique. His unconventional leadership helped create Apple’s two most important products of the 70s and 80s: the Apple II and the Macintosh. Unfortunately for Jobs, the CEO he had recruited, John Sculley, was not happy with the risks Jobs was willing to take. After a short power struggle that left Sculley in control of Apple, Jobs left the company in 1985.

After puttering around for several months, Jobs decided that he would return to the computer industry. He invested $7 million to create a brand new company, NeXT Inc.

After puttering around for several months, Jobs decided that he would return to the computer industry. He invested $7 million to create a brand new company, NeXT Inc.

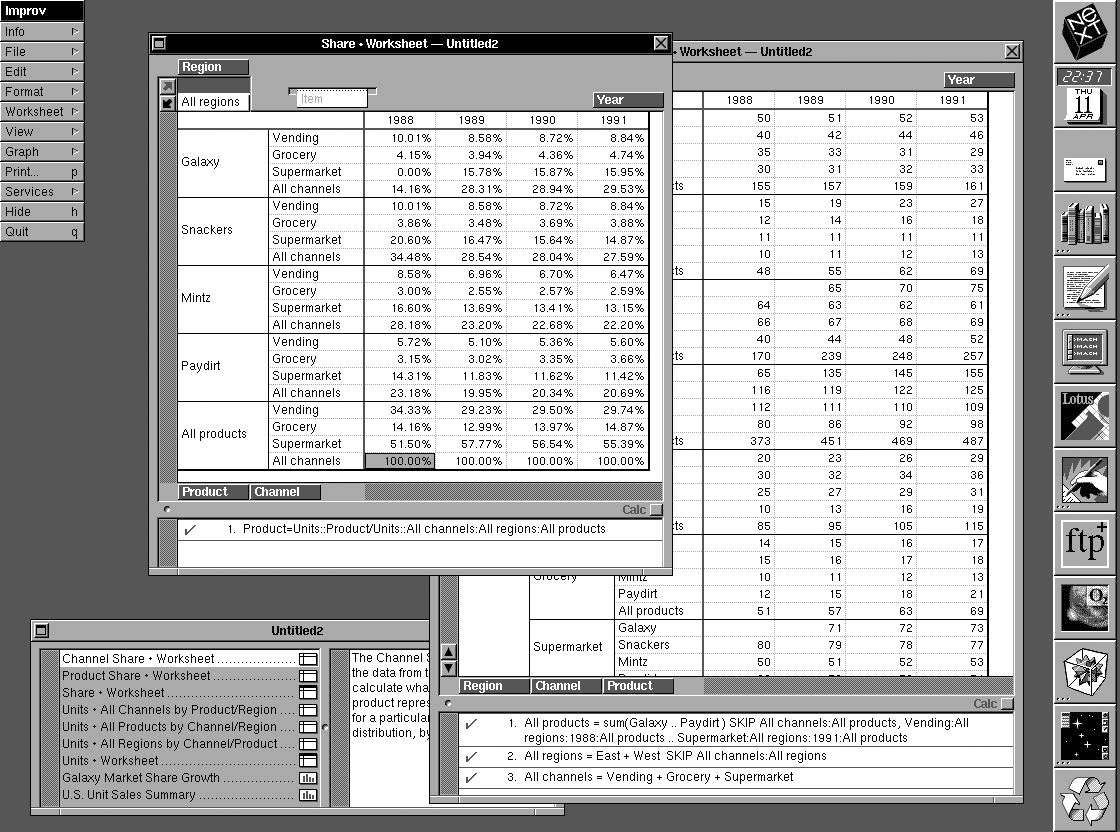

Unsatisfied with the software available at the time, Jobs set about building a team of software developers to create a new programming environment that would run on top of another operating system. The environment would be object oriented, which to an end user means that programs could share information and features.

Jobs also hoped to integrate many of the features that were only available on high-end workstations and Macs, including a WYSIWYG interface, an intuitive user interface, and a fully multitasking operating system (which the Mac did not yet have).

Reluctant to release a brand new operating system and computer, NeXT searched for a host operating system for their environment. The company considered SunOS and several other Unix derivatives but was unable to find a platform where all of the features Jobs wanted could be implemented easily.

Jobs went to several Macintosh developers and sold them on the idea. Because of Apple’s copyright policies, several unreleased programs that had been developed at Apple were owned by developers, who now worked at NeXT. As a result, the first commercial product that NeXT released was WriteNow, which was developed in tandem with MacWrite (it was meant as a fail-safe in case MacWrite didn’t pull through).

WriteNow generated some needed revenues for the company and also attracted new investors. In early 1986, Ross Perot became the second largest shareholder in the company.

NeXTstep

Still focused on development of the new operating system and computer, Jobs recruited Avie Tevanian, a major developer of the Mach microkernel, to help create the new NeXT operating system, later dubbed NeXTstep. (Mach was originally developed at Carnegie Mellon and was meant to be a proof of the microkernel concept.)

Instead of incorporating many features into one large kernel, microkernel operating systems contained only enough code in the kernel to act as a basic interface between the software and core hardware. Everything else was handled by other programs, called servers. Each server sent data to other servers through the microkernel.

Carnegie Mellon managed to port BSD (a version of Unix developed at UC Berkeley in conjunction with Bell Labs in the 1970s) to Mach, where each part of the system functioned as a server. This structure lent itself well to an object oriented operating system, and Jobs was enthusiastic about the proposition.

Hardware

The hardware that the new software ran on would be almost as important as the software itself. A slow, unresponsive computer would reflect poorly on the software. As a result, the hardware engineers were eager to adopt a high performance CPU. At the time, several new RISC designs were being introduced, including the ARM, MIPS, and SPARC.

Hesitant to adopt one of the more established (and very expensive) processors, NeXT wanted to adopt Motorola’s RISC chip, the 88000. Unfortunately, the 88000 would not be available for several years, and its biggest customers were moving to new chips (Apple had intended to use the 88000 in its Jaguar system, right). Instead, NeXT adopted the 68030 processor, the same CPU that was used in the Macintosh and early Sun workstations.

At this time, NeXT’s efforts attracted Apple’s attention. Because so many NeXT developers were from the Macintosh team, Apple accused NeXT of stealing Apple’s intellectual property. Apple sued, and in an out-of-court settlement, NeXT was barred from competing with the Macintosh. As a result, NeXT was relegated to the high-end market not populated by Macs. NeXT was also allowed to continue marketing any unreleased software that the former Macintosh developers had created at Apple.

Objective-C and Display PostScript

Work on NeXTstep pressed on through 1986 and 1987. It was relatively easy for the developers to port Mach and BSD to the new hardware platform, but it proved more difficult for the group to create the new servers that would differentiate NeXTstep from its competition. Objective-C and Display PostScript were the two most ambitious project.

In order to have an object oriented operating system, an object oriented programming language was required. C++ was not available at the time, so NeXT decided to use Objective-C. Developed in the early eighties by Brad Cox at Stepstone, Objective-C was one of the most respected object oriented programming languages available at the time. Unlike “object oriented enabled” versions of languages like Ada or BASIC, Objective-C had a very low overhead. It also had a syntax similar to C, making it easier for most programmers to learn and use.

Not satisfied with the Mac’s method of using QuickDraw for the display and PostScript for printing, Jobs wanted what the user saw on the display to exactly mimic the printed page. Traditional methods of rendering the graphics were not suitable, so Jobs approached Adobe about bringing PostScript to the desktop. Adobe was interested. NeXT began the arduous task of porting PostScript to NeXTstep and actually creating Display PostScript.

The NeXTstep Interface

By 1987, all of the major components of the operating system were finished or almost finished. The user interface was still in its infancy, but it was progressing well. Instead of using a strict desktop metaphor (like the Macintosh) to manipulate files and programs, NeXTstep used a looser interpretation.

The most defining feature of the NeXTstep interface was its dock, where frequently used programs or filed programs could be linked and where applets could dock. There was no desktop in NeXTstep; users would access their file system through an icon in the dock. Because of the use of Display PostScript, the graphics were all very crisp, which made the interface look very good.

At the same time that the software was being developed, the hardware was being created. Centered around a 68030 processor, the NeXT workstation’s most unique features were its enclosure and its inclusion of a magneto-optical disk drive.

Hard drives were very expensive at the time, and the NeXTstep operating system was very large, requiring around 200 MB. A hard drive of that capacity would cost thousands of dollars, so the hardware engineers decided to adopt the up-and-coming magneto-optical (MO) format. Slower than an ordinary hard drive, a magneto-optical disc was also substantially faster than floppy disks. NeXT was the first company to incorporate aan MO drive in a production computer.

Designed by frog (the same company that had designed the Apple IIc and the Mac II series), the new computer’s case was unique. Eschewing a standard desktop case, NeXT used a 12″ magnesium cube. A completely automated factory was constructed to produce the computer (named the NeXTcube), and the first Cube was shown to a packed audience in New York city in October 1988.

Designed by frog (the same company that had designed the Apple IIc and the Mac II series), the new computer’s case was unique. Eschewing a standard desktop case, NeXT used a 12″ magnesium cube. A completely automated factory was constructed to produce the computer (named the NeXTcube), and the first Cube was shown to a packed audience in New York city in October 1988.

Using a beta version of NeXTstep (version 0.9), NeXT began shipping Cubes in limited numbers to universities and publishers in 1989.

Most of the reviews and articles written about the computer focused on the hardware, not the software. Because of the choice to use a magneto-optical drive, performance was very sluggish in comparison to hard drive-based computer, but reviewers usually blamed it on the software. (Imagine running your computer from a CD-ROM to get some idea of the performance hit.)

Each NeXTcube was bundled with a 17″ megapixel grayscale display (1120 x 832 pixels with four shades of gray), a 400 dpi laser printer (which was dramatically less expensive than comparable printers, since the computer included a PostScript interpreter), and built in ethernet networking.

Each NeXTcube was bundled with a 17″ megapixel grayscale display (1120 x 832 pixels with four shades of gray), a 400 dpi laser printer (which was dramatically less expensive than comparable printers, since the computer included a PostScript interpreter), and built in ethernet networking.

NeXT bundled lots of software on the magneto-optical disc, including the complete works of Shakespeare, an email client, and the complete Oxford English Dictionary.

Jobs said of the new computer, “This will either be the last machine to make it or the first to fail.”

A 25 MHz 68040-based NeXTcube was officially launched in September 1990, and it was met with brisk sales to universities and government agencies.

Sensing that the opportunity to introduce a brand new hardware platform was fast fading as IBM clones proliferated in the corporate world, Jobs decided to give heavy discounts to universities and research institutions, hoping that students would become hooked on the machines and encourage their future employers to use them. The strategy was somewhat effective, as several major universities adopted the Cube for their computer science programs.

In 1990 and 1991, NeXT promoted its operating system heavily, writing articles for many computer periodicals including Dr. Dobbs. The most common exercise they would contribute was several pages of code in C++ simplified down to several lines of Objective-C. This way, the company was able to attract attention to its software rather than its rather sluggish computers.

New Hardware

In early 1991, NeXT abandoned the magneto-optical drive in the Cube and created a brand new (slimmer) workstation built around a hard drive, the NeXTstation.

In early 1991, NeXT abandoned the magneto-optical drive in the Cube and created a brand new (slimmer) workstation built around a hard drive, the NeXTstation.

Another complaint about the Cube was how difficult it was to exchange information between two Cubes – it was impossible without a network, because the machines had only one drive, and that held the operating system and thus could not be removed while the computer was in use. To address this, the NeXTstation included a floppy drive.

All of this was housed in another frog-designed case that resembled a pizza box (a little larger than a Centris 610).

The NeXTstation also came bundled with a brand new version of NeXTstep that supported color and more networking protocols. At the same time, NeXT released an upgrade for Cube users that allowed them to use a color display and a hard drive.

NeXTstep Becomes OpenStep

The new hardware was much more successful than the earlier Cubes, but it still did not sell very well. In 1993, NeXT began a major effort to port NeXTstep to several different platforms, including MIPSD, PA-RISC, SPARC, and x86. This marked the end of NeXT’s hardware line.

This announcement drew the attention of Sun, which was eager to beat Microsoft to market with an object oriented environment. (Microsoft had announced that its Cairo operating system, a version of Windows that never made it to market, would be released in 1996.)

Sun and NeXT made an agreement to port the NeXTstep environment (not the entire operating system) to Sun’s Solaris. It was relatively easy, as all NeXT had to do was remove Mach and rewrite several of the low level servers to interface properly with Solaris. The new product would be called OpenStep.

After it became clear that Cairo was only vaporware, Sun lost interest in OpenStep for Solaris and focused its efforts on readying Java for release. OpenStep on Windows was very popular, though. It was adopted by many financial institutions.

NeXT also released WebObjects, a specialized database system for the Internet. The product was adopted by many different companies, including Dell.

Full Circle

Despite a spate of relatively successful products, NeXT was not doing well. Ross Perot had sold his share of the company, and Jobs spent very little time there. Many journalists believed that NeXT would quickly run out of cash and close quietly.

At the same time, Apple was going through its largest losses ever. Apple management decided that the best way to rejuvenate their platform would to release a brand new operating system that could compete head-to-head with the forthcoming consumer version of Windows NT.

Most analysts expected Apple to acquire or license BeOS from Gassée’s Be Inc. and quickly release an Apple branded version (BeOS was already available for Power Macs and had a Mac-like interface). Be apparently demanded too much money, so Apple decided to look elsewhere.

After considering several alternatives, including Solaris and Windows NT, Apple decided to acquire NeXT and base the next generation Mac OS on OpenStep. Apple acquired NeXT in December 1997, and Steve Jobs returned to Apple after a dozen years away.

Also see The NeXT Years: Steve Jobs before His Triumphant Return to Apple.

Further Reading

- Steve Jobs, Wikipedia

- John Sculley, Wikipedia

- Avie Tevanian, Wikipedia

- NeXT Computer, Wikipedia

- Sun Microsystems, Wikipedia

- Mach kernel, Wikipedia

- Motorola 88000, Wikipedia

- BSD (Berkeley Software Distribution) Unix, Wikipedia

- Objective-C, Wikipedia

- C++, Wikipedia

- NeXTstep, Wikipedia

- frog design

- Sun Solaris, Wikipedia

- OpenStep, Wikipedia

- Why BeOS Lost, Chris Lozaga

Bibliography

Some of the sources used in writing this article:

- Apple: The Inside Story of Intrigue, Egomania, and Business Blunders, Jim Carlton

- Infinite Loop, Michael Malone

- The Second Coming of Steve Jobs, Alan Deutschman

- Apple Confidential 2.0, Owen Linzmayer

- Odyssey: Pepsi to Apple . . . a Journey of Adventure, Ideas & the Future, John Sculley

- Wikipedia

Keywords: #nextstep

Short link: http://goo.gl/v1HBgc

searchword: fullcircle

I think it’s worth noting in any history of NeXT that the object oriented programming environment, and probably helped by its UNIX underpinnings, enabled Sir Tim Berners-Lee to code the World Wide Web using a NeXT computer, and run the first web browser/editor and server on one as well.

Pingback: Quora