2000: With the proper wired infrastructure in place, there is no reason why e-businesses can’t operate virtually anywhere in the world. My own experience is a case in point. I live in an unlikely spot – the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia, Canada, which is the extreme boonies even in a rural Nova Scotian context. My news editor colleague at Applelinks.com, the formidable John Farr, lives 7,000 feet high in the Rocky Mountains near Taos, New Mexico. We both “cyber commute” daily via the Web to the Applelinks server in New York.

Thanks to the Internet, I can successfully do my job as an online news editor and columnist while living in this beautiful but remote spot. I do most of my research on the Web, and conduct interviews by email or telephone.

I also write columns for Low End Mac and MacSimple, as well as syndicating a newspaper column to major newspapers across Canada twice a week via email, and I contribute to the other publications I write for in Canada, the U.S., and Australia the same way. Indeed, I haven’t submitted a story as hard copy for years.

It wasn’t always like this, and looking back over the 14 years I’ve been in the freelance journalism game, it’s remarkable how much things have changed. Back in 1986, I composed columns and articles in longhand with pencil and paper, and then I typed the final drafts on a big Remington manual office typewriter, which still reposes about ten feet away from where I’m sitting right now. It may have been two years since I last had the dust cover off it and nearly a decade since I used it for anything more substantial than addressing a letter. I should get rid of it, I guess, but the old boat anchor has sentimental value.

I “graduated” from the Remington to a hulking big Wang word processor, which my cousin got for me at a giveaway price when the company he worked for switched to PC 386s. The Wang introduced me to the world of digital data and electronic manipulation of text. It was menu-driven, used command lines, and ran on 5-1/4″ floppy disks – one disk drive for the system and the other for working data. I haven’t a clue how much memory it has (I still have the Wang, too), but I’d be surprised if it was more than 32 KB.

Still, the old Wang was a big advance from the Remington, and I reveled in being able to play with text, move paragraphs around, and experiment with editing changes without messing up a page of laboriously typed copy. It had a very nice keyboard as well, and its command line interface put DOS to shame for user-friendliness.

Still, at the end of the day, the Wang produced pages of hard copy from its integrated daisy-wheel printer. Theoretically, one could send one’s work to editors on a floppy, but in practise I didn’t know anyone else who had a Wang machine, and the disks it created had a proprietary format, so in practical terms, I still had to send stories to editors on paper via conventional mail.

About a year after I got the used Wang, I was doing a lot of work for a publisher of a family of magazines. When I say a lot, I mean a lot. I can recall a couple of issues of one journal in which I wrote 26 to 28 articles each, and six of the eight people listed on the masthead were me writing under my own name and five pseudonyms. This obviously involved a lot of retyping for the publisher’s office staff, and he began to hint pointedly that I should get a computer. I had been thinking about doing so anyway and was considering several 286/386 DOS Windows machines, reasoning that IBM compatible were the most popular so they must be better.

Mac Plus with LaserWriter

However, in one of those life-transforming watershed coincidences, it turned out that this magazine publisher, who represented my main writing market at the time, ran a Macintosh shop, and he implored me to get a Mac. I had misgivings, but the compatibility angle seemed to make logical sense. In another coincidence, a university professor friend of mine was looking to sell his Mac Plus with 1 MB of RAM and a whopping big 20 MB Seagate external hard drive along with an ImageWriter II printer, all in great shape with the original boxes and manuals, for Can$1,000 (the bundle had cost him four times that new). That was less than I would pay for a 286 PC with no printer, so I made the deal.

The little Mac with its graphical user interface (GUI) was a revelation, although I didn’t much like the mouse at first, and the Apple keyboard was pathetic compared to the lovely one on the Wang (which is still nice by today’s standards). However, the graphical user interface displayed on the Plus’ sharp little nine-inch black & white screen was a revelation, and I was now able to submit stories on floppy disk in Microsoft Word format (first 4.0, then 5.0). I soon upgraded to a luxurious 2.5 MB of RAM, which allowed me to keep Word and HyperCard open simultaneously under System 6‘s MultiFinder. This was a lot more convenient than opening and closing each program whenever I wanted to paste something from one into the other.

I still had to mail my story disks (no Internet yet), but it sure saved a lot of printing and retyping at the other end. However, a lot of the publishers I sold to in the mid-’80s weren’t equipped to handle digital submissions, so I still gave the old dot-matrix ImageWriter II a good workout for a few years as well, even long after I upgraded to a brand new LC 520 in January ’94.

The LC 520, with its 25 MHz 68030 chip and 8 MB of RAM, seemed amazingly fast after the Mac Plus, and it’s 14″ 640 x 480 Sony Trinitron monitor was expansive as well as displaying very nice color. Good as it was, however, I still missed the crisp sharpness of the Mac Plus display.

The LC 520, with its 25 MHz 68030 chip and 8 MB of RAM, seemed amazingly fast after the Mac Plus, and it’s 14″ 640 x 480 Sony Trinitron monitor was expansive as well as displaying very nice color. Good as it was, however, I still missed the crisp sharpness of the Mac Plus display.

The LC 520 also came with a 2x Sony CD-ROM drive, whose silent operation and absence of vibration still seems very civilized compared with the noisy 20x unit in my WallStreet PowerBook. The Sony drive is caddy-loading, but it has proved dependable as an anvil for more than six years. I dithered over whether to order the standard 80 MB hard drive or the humongous, optional 160 MB unit. After all, I hadn’t even filled the Mac Plus’s 20 MB drive. A wise Mac veteran persuaded me to get the larger drive, which of course I had no trouble filling – and then some.

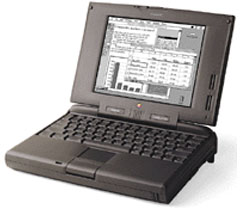

PowerBook 5300

By the time I bought my first PowerBook, a 5300, in 1996, mailing floppies had become pretty much the norm, and I probably printed my last hard copy article submission sometime early that year. The Internet arrived at the local public library in 1996 (on PeeCees, alas) as well, which meant that I could finally send stories by email, although it meant a 12-mile drive one way. We finally got dial-up Internet access here on Hallowe’en 1997, and of course, the rest is history.

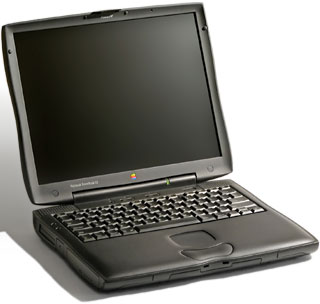

My current G3 Series II 233 (WallStreet) PowerBook doesn’t even have a floppy drive, and the ImageWriter II (still going strong) gets used maybe every couple of months to print a hard copy letter.

My journalistic endeavours are all transmitted to editors and publishers over the Web now, and a significant proportion are published there. Occasionally I will compose a rough draft with pen and paper, but with electronic files and Web searches having largely replaced my three file cabinets full of hard copy resources and clippings for research work, most composition is done on the computer now.

The WallStreet is definitely the best of the four Macs that I’ve owned, but my favorite remains the 5300, which served me as my daily workhorse for nearly three years, and which never missed a beat or required service. My daughter is using it these days, and it is still going strong. Fast it is not, but if I could build my own PowerBook, it would probably be about the size and shape of the 5300, which I find ideal, and which looks like a subnotebook when parked next to the WallStreet.

The WallStreet is definitely the best of the four Macs that I’ve owned, but my favorite remains the 5300, which served me as my daily workhorse for nearly three years, and which never missed a beat or required service. My daughter is using it these days, and it is still going strong. Fast it is not, but if I could build my own PowerBook, it would probably be about the size and shape of the 5300, which I find ideal, and which looks like a subnotebook when parked next to the WallStreet.

In fact, a 5300 with a G3 CPU, modern motherboard architecture, and a DVD-ROM drive would be my ideal computer. Perhaps Apple will someday build an “eBook” resembling these specs.