Microsoft was deeply involved in the development of the Macintosh. Microsoft had been the first outside developer to get a Macintosh prototype. The prototype was promptly nicknamed SAND (Steve’s Amazing New Device) by Bill Gates and Charles Simonyi.

Microsoft developed productivity software that the Macintosh desperately needed to make the Macintosh a contender in corporate markets.

License This

After the public unveiling of the Macintosh, Bill Gates personally wrote John Sculley, urging him to license the software and ROMs to outside manufacturers so that the Macintosh would become the new standard in personal computing. (This was two years after Microsoft began development of Interface Manager, which was renamed Windows shortly before release.)

The proposal, dated June 25, 1985, was soundly rejected by Jean-Louis Gassée, who was given control of the Macintosh and Lisa after Steve Jobs had been stripped of management responsibilities. Gassée reasoned that the Macintosh was so vastly superior to the existing PC graphical environments that Apple would never face any serious competition and would be able to rely on profit-rich hardware sales (with margins over 55% until the early 90s).

Besides protecting profits, Gassée was probably a little distrustful of Microsoft’s motives. It was in Microsoft’s interest to maintain the IBM PC standard for as long as possible, since Microsoft controlled most of the operating system market and most of the developer’s tools market. In Gassée’s mind, the proposal could have been an attempt to sabotage the Macintosh.

In later interviews, however, Bill Gates points out that Microsoft made a lot more money selling a Mac user a copy of Word and MultiPlan (the predecessor of Excel) than selling an OEM DOS license, so a Macintosh standard would have benefited both companies in the long term.

In later interviews, however, Bill Gates points out that Microsoft made a lot more money selling a Mac user a copy of Word and MultiPlan (the predecessor of Excel) than selling an OEM DOS license, so a Macintosh standard would have benefited both companies in the long term.

Despite Gassée’s objections to the plan, Sculley believed that it could help Apple establish the Macintosh as the personal computer standard, supplanting the IBM PC and MS-DOS.

Sculley had Dan Eilers, one of his aides, prepare a list of possible licensing deals. The list of suggestions included selling entire system boards to manufacturers, porting the Macintosh software to the IBM PC and selling the software to consumers, partnering with a workstation vendor, and others.

Salivating Over the Mac OS

Armed with a list of proposals, Sculley sent a vice president, Chuck Berger, to travel the nation talking to possible Macintosh licensees. Interest was astounding. Eilers and Gates had both suggested consumer electronics companies with no presence in the US computer market, but Berger found that even large, well established companies were interested in licensing the Macintosh. Apollo, DEC, and Wang all gave Berger letters of intent.

By far the most promising prospect was AT&T. The company was so interested in bundling the Macintosh software on its Unix workstations that CEO Bob Allen personally contacted John Sculley.

Apple was poised to license the Macintosh software to several major manufacturers and get the Macintosh standard firmly established in the business market, but Gassée would have none of it. He became more and more adamant in his opposition to the plan. He wouldn’t have any other company cannibalize Apple’s Macintosh sales, even if it meant establishing an industrywide standard.

Forget It

During the winter of 1985, Sculley dropped all plans to license the Mac OS, only one year after he sent Chuck Berger to drum up support for the plan.

Macintosh sales were collapsing. Apple had originally forecasted that it would sell 50,000 Macs a month during 1985, but the real figure was closer to 20,000.

With Macintosh sales tanking and no licensee in sight, Gates pressed ahead with Windows. On November 15, 1985, in the midst of the COMDEX trade show, Gates revealed Windows to a lukewarm response.

There were already other companies with far more impressive environments than Windows. Digital Research GEM mimicked the Mac interface almost perfectly – and had color to boot. VisiCorp VisiOn had a built-in office suite. Tandy DeskMate was bundled on every PC compatible Radio Shack (then one of the largest cloners) sold.

Windows 1.0 ‘No Threat’

Microsoft Windows 1.0 had a tiled interface; windows couldn’t overlap each other. Instead, users could move windows around like a jigsaw puzzle.

When a user only needed one app at a time, he or she could zoom it to take up the entire display. Apps could also be minimized to the “desktop”, a dock running along the bottom of the screen.

When Gassée saw Windows 1.0, he dismissed the software as no threat.

But when Sculley saw the software, he was enraged. Microsoft had been provided early prototypes of the Macintosh and some source code to help optimize Word and MultiPlan. Now Windows had a menu bar almost identical to Apple’s. Windows even had a Special menu, containing disk operations. Other elements were strikingly similar. Windows came bundled with Write and Paint, both mimicking Apple’s MacPaint and MacWrite.

Sculley couldn’t allow Microsoft, a company that had only $25 million in sales in 1983 (compared to Apple’s revenues well over $1 billion) to so flagrantly rip off the Mac, even if Word and MultiPlan accounted for two-thirds of all Macintosh software sales.

He dispatched an Apple lawyer, Jack Brown, to Microsoft’s headquarters to threaten Bill Gates with a lawsuit for violation of Apple’s copyrights on the Macintosh.

Toe to Toe

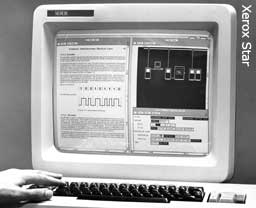

Gates was incensed. Development of Windows had begun before the Macintosh was even demonstrated to Microsoft. Besides, Microsoft had licensed GUI elements from Xerox, including a desktop-style interface used on the Xerox 8010, the commercial version of the Alto. (Apple had also licensed the GUI from Xerox for $100 million in Apple stock.)

Gates was incensed. Development of Windows had begun before the Macintosh was even demonstrated to Microsoft. Besides, Microsoft had licensed GUI elements from Xerox, including a desktop-style interface used on the Xerox 8010, the commercial version of the Alto. (Apple had also licensed the GUI from Xerox for $100 million in Apple stock.)

Bill Gates supposedly called Sculley personally and told him that if Apple was going to sue Microsoft, “I want to know it, because we’ll stop development on all Mac products. I hope we can find a way to settle this thing. The Mac is important to us and to our sales.”

Gates and Microsoft’s chief counsel, Bill Neukom, flew down to Cupertino, and he met with Sculley in the boardroom one-on-one.

Sculley couldn’t leave the meeting without some sort of concession from Microsoft, and Gates wanted Apple’s cooperation in the nascent (and highly profitable) Microsoft Office.

Both men wanted to avoid a drawn out lawsuit. Gates was gearing up for the wildly successful Microsoft IPO, and Sculley was still trying to popularize the Macintosh.

Ultimately, Sculley agreed to license the Macintosh’s “visual displays” to Microsoft to use in software derived from Windows 1.0, and Microsoft agreed to continue developing its Mac products and promised not to release Excel (a feature-rich replacement for MultiPlan) for any other platform for two years.

Sculley had Al Eisenstat, Apple’s chief counsel, draw up a contract, and the two men signed on November, 22 1985, exactly one week after Windows 1.0 was released.

After the contract was signed, Sculley implemented a major reorganization that structured the company more like a traditional corporation with accountable executives. Pie in the sky projects like BigMac, a project to create an Apple workstation running a Unix-Macintosh hybrid, were canned. Sales began to improve in 1986, and by 1987 Apple’s net income had doubled over 1985. Sculley was being lauded in the press for his turnaround at Apple and was being considered a possible successor to Kodak’s struggling CEO.

Windows 1.0 Fails to Open Market

Meanwhile, the first version of Windows failed to catch on. The only major application written for Windows 1.01 (the first version available to the public) was Aldus PageMaker. PageMaker was actually bundled with a runtime version of Windows, since almost no PC user owned Windows.

That began to change with the release of Windows 2.0 on November, 1 1987.

Windows 2.0 was a huge improvement over version 1.0, and Sculley recognized it. The new version offered overlapping windows, multitasking, and a limited object oriented environment (through a rudimentary version of OLE).

Besides the new features, Windows 2.0 actually had programs for it. During the press conference, Microsoft revealed that it had finished developing Microsoft Word for Windows and Microsoft Excel for Windows, and that outside companies including Aldus, Corel, and Microtek were all working on Windows 2.0-compatible programs.

Sculley was shocked at how much Windows 2.0 resembled the Macintosh, and he believed this to be a breach of contract. Sculley, along with most of the Apple legal team, believed that the November 1985 agreement gave Microsoft permission to use Macintosh displays in Windows 1.x, but not in any later versions.

Talk to the Judge

Without warning, Apple filed suit against Microsoft in federal court on March 17, 1988 for violating Apple’s copyrights on the “visual displays” of the Macintosh. (Apple also filed suit against HP for its NewWave environment that ran on top of Windows 2.0.)

Apple’s suit included 189 contested visual displays that Apple believed violated its copyright.

Microsoft countersued, but it failed to stem the bad publicity. Windows’ development community was terrified that any court ordered changes to the software would render their products incompatible and make Windows undesirable to consumers. Borland’s CEO said it was like “waking up and finding out that your partner might have AIDS.”

Fortunately for Windows developers, Judge W. Schwarzer ruled on July 25, 1989, that 179 of the 189 disputed displays were covered by the existing license, and most of the other ten were not violations of Apple’s copyright due to the merger doctrine (the merger doctrine stipulates that ideas cannot be copyrighted). In the case of Apple vs. Microsoft, many of the displays Apple contested were ideas and could not be protected by copyright.

The lawsuit was decided in Microsoft’s favor on August 24, 1993.

Strained Relationship

The lawsuit single-handedly tainted Microsoft-Apple relations until 1997, when Microsoft pumped $100 million into Apple.

The 1985 agreement hurt Sculley almost as much as the judgment did. Mac users everywhere were shocked that the Apple CEO would give Microsoft unfettered access to the Macintosh interface in exchange for Excel and Word.

Apple appealed the ruling and made it all the way to the Supreme Court, which declined to hear the case.

Further Reading

- MultiPlan, Wikipedia

- Apple Confidential 2.0, Owen W Linzmayer

- COMDEX, Wikipedia

- GEM, Wikipedia

- VisiOn, Wikipedia

- DeskMate, Wikipedia

- Adobe PageMaker (originally Aldus PageMaker), Wikipedia

- OLE (Object Linking and Embedding), Wikipedia

- HP NewWave, Wikipedia

- Merger doctrine, Wikipedia

- The ‘Lectric Law Library’s Lexicon on Merger Rule/Doctrine

- Apple Computer, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., Wikipedia

Keywords: #applevsmicrosoft #microsoftguilawsuit #windowsguilawsuit

Short link: http://goo.gl/qUV7RM

searchword: applevsmicrosoft

Images adapted from ToastyTech.