“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” – Lord Acton

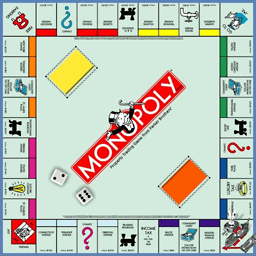

Do you remember playing Monopoly®?

Do you remember playing Monopoly®?

As you learned to play with your brothers and sisters and friends, you probably experimented and settled on a strategy to try to win the game. Some people buy every property they land on and hope that luck leads them to complete the sets that lead to greater profits. Others hold back, saving precious investment dollars for the big properties.

In a game with many players, Boardwalk and Park Place (which are real streets in Atlantic City, New Jersey) are the greatest asset: Smaller players can be completely wiped out by a single hit, and the income from these properties can let you easily survive the disorganized spaces held by the other players.

Did you ever wonder, when you were playing, why the rents on properties went up when you got a complete set?

Because that’s the point of the game, you might say. It’s how you gain advantage. You complete sets so you can complete more sets.

The real reason, however, is a little more sinister. The rents in a particular set (the yellows, for example) go up because you own the houses in that neighborhood. All of them. So you can charge more for your rents if someone passes through there, because they have no choice. They have to pass through there.

Each little set – each color – represents a little microcosm of the larger game. If you have a monopoly on a neighborhood, you can charge more. If you have a monopoly on the railroad, you can charge more. Why? Because there aren’t any alternatives.

When there aren’t any alternatives, you can charge whatever you want and do whatever you want.

Monopolies

The origins of monopolistic behavior are as old as politics or commerce. However, some notable examples help us understand why monopolies are not a good thing for the citizens subjected to them.

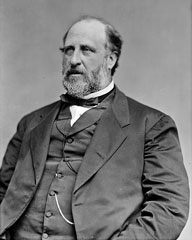

Boss Tweed

William “Boss “Tweed, a senator and politically active figure in New York during the period 1850-1870, organized a group of men that controlled all the labor contracts and budgets for the city of New York. His basic tactic was to arrange (one way or another) for his own companies or the companies of his cronies to be the only companies eligible to complete certain contracts, such as building structures like the Brooklyn Bridge.

William “Boss “Tweed, a senator and politically active figure in New York during the period 1850-1870, organized a group of men that controlled all the labor contracts and budgets for the city of New York. His basic tactic was to arrange (one way or another) for his own companies or the companies of his cronies to be the only companies eligible to complete certain contracts, such as building structures like the Brooklyn Bridge.

As the sole qualifying bidder, the companies could write any amount on the bid, far above the actual expenses required. The excess funds, of course, returned to Tweed and his gang. Eventually the City of New York acquired huge debts, and its credit was ruined because no one would invest in municipal bonds from the city. Tweed was eventually ousted and jailed, but not before he and his gang swindled the taxpayers of New York out of millions of dollars.

Tweed, in effect, not only owned Boardwalk and Park Place, but the game board itself.

Monopoly vs. Anti-Monopoly

The game of Monopoly has an interesting history as well. Any simple search about the game will turn up many links about how Parker Brothers was saved from bankruptcy by the wild success of the game.

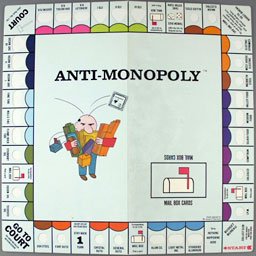

However, if you instead search for anti-monopoly, you will discover that there is a game called Anti-Monopoly that was embroiled in a ten-year lawsuit with the Monopoly people over the use of the word monopoly. Read the Anti-Monopoly story to find out how Hasbro, which for all practical purposes has a monopoly over board games, continues to obstruct the distribution of this game.

However, if you instead search for anti-monopoly, you will discover that there is a game called Anti-Monopoly that was embroiled in a ten-year lawsuit with the Monopoly people over the use of the word monopoly. Read the Anti-Monopoly story to find out how Hasbro, which for all practical purposes has a monopoly over board games, continues to obstruct the distribution of this game.

Monopolies are bad because, once established, the alternative sources of competition are crushed. After that is accomplished, the monopolists can do whatever they want.

Who’s to stop them? Even if the monopoly is subsequently broken up by legal or other means, no one is left who can fill the void – at least at first.

This is why Standard Oil was broken up in 1911.

Ma Bell & the Baby Bells

This is why “Ma Bell” was broken up into the “Baby Bells”. Some of the younger readers of this site might not know that there used to be one phone company, one long-distance company. They could charge whatever they wanted, and prices began to have little connection to the services offered.

Today, of course, the system is much more complicated than it used to be. Before the breakup, you could dial 1- to make a long distance call, and that was that. Now you have to decide which company will give you the “1-” service? Do I dial 1-800-COLLECT? Do I use the discount phone card from Walmart?

Competition is messy; it’s not as simple as monopoly – but you get more services. You get cell phones, caller ID, voice mail, and conference calling. It opens up possibilities a monopoly would never think to offer, because they don’t have to.

If AT&T hadn’t been broken up, would we have Caller ID? DSL? Push-button phones? Okay, maybe push-button phones.

Did you know you used to have to lease your phone from the phone company? You didn’t own it. You paid a fee each month for the privilege of having it. There was no such thing as a phone store. Phones were treated like some cable-modem companies treat cable modems today – now there’s an interesting thought.

AT&T and @Home

If your life was disrupted by the @Home fiasco, like mine was, remember it was AT&T that provided the ridiculously low bid for @Home (in fact, after the changeover, one of the sites I was directed to actually had lobid as part of its URL) that caused the big service interruption for everyone, forcing domain name changes that no one enjoyed – and that some users have yet to recover from.

AT&T had a voting stake in @Home, which many believe they used to bring @Home to the end for their own purposes. AT&T obviously expected this outcome, for they had Web services set up, help files, and converter software ready – even for the Mac – within a couple of days. No one has Mac software ready in advance unless they are just thinking way in advance.

I don’t think AT&T expected this outcome. I think they caused it – deliberately – to remove the @Home middleman from collecting fees. Old habits, it seems, die hard.

The Microsoft Monopoly

Why is it bad that Microsoft has a monopoly on operating system software? Because if they ever win – and I mean really, truly win – by crushing AOL’s instant messaging service, by eliminating Apple Computer from the marketplace simply by stopping development of Office for the Mac (as some pundits claim would happen), by undercutting competitor Sun by offering free server software (for a while), then – when they have completely, truly won – some things would change.

Why is it bad that Microsoft has a monopoly on operating system software? Because if they ever win – and I mean really, truly win – by crushing AOL’s instant messaging service, by eliminating Apple Computer from the marketplace simply by stopping development of Office for the Mac (as some pundits claim would happen), by undercutting competitor Sun by offering free server software (for a while), then – when they have completely, truly won – some things would change.

Innovation (even using Microsoft’s anemic definition of it) would grind to a halt. No new features would be developed. No new “improvements” to Office. No extra features for FrontPage. [Update: FrontPage, Microsoft’s WYSIWYG HTML editor, was discontinued in late 2003.]

And a single copy of Windows, improved with a new colorful box, would cost $300. Then $500. Then $1,000. Or maybe $20 per month, every month, forever.

Surely not, you say. Microsoft is committed to “innovation.” They talk about it with every breath. Besides, improving software is fun. Engineers can’t help it. They’ve got to see if they can squeeze a little more life into an old product.

Engineers don’t run Microsoft. Business majors do. And if you want more profits from a product that doesn’t need improvement in a saturated market, what do you do? Cut the engineering staff. Charge more for the product. Cut off competition.

Microsoft is already moving toward a subscriber model. Product activation is a way of ensuring a revenue stream from a sole-source vendor into the indefinite future. Pay up, or we cut you off. [Update: In 2011, Microsoft Office 365 was launched as a subscription-only version of Office. In 2014, when Office finally arrived for the iPad, you could only use it to edit documents with an Office 365 subscription.]

You can’t go find another phone company with cheaper rates when there isn’t one. This is monopolistic behavior – in fact, it’s the definition of monopolistic behavior.

In case you’ve missed my point, let me make it crystal clear: Monopolies are bad.

If Microsoft wins; everyone loses.

The shortsightedness of IT directors, who say things like, “I don’t want to maintain a cross-platform network,” and “things would be simpler if we just had one standard, so from now on, everyone uses Office,” unilaterally and without considering the larger consequences, will eventually lead to the downfall of the entire computer revolution.

I believe that with all my heart. That can’t be good for users. It can’t.

Resistance to competition at the grass roots level comes mainly from IT directors and technicians. They are the ones who establish the guidelines by which computers are purchased. They set the “standard” which says the OS must be Windows “because it’s compatible with our network.”

They say that Mac users are fanatics, blindly loyal to a computer company which abandons users of older equipment, doesn’t really endorse things like Mac evangelism, is as much focused on profits as the empire in Redmond. That may be true.

But who are the real fanatics here? The real fanatics are the people who work on behalf of the monopolist. They’re even worse than the Macolytes, because they don’t even know, or care, that they’re as devoted to providing money and power to a proven monopolist.

- The unions that cooperated with Boss Tweed; the suppliers, the political agents, the bookkeepers, the shop owners who sold only to the approved construction workers; the landlords who provided reasonable rates only to Tammany Hall supporters – all profited individually while contributing to the larger problem.

I say the IT directors, the individual technicians, the salesmen who gently guide you toward the Wintel side of CompUSA, the computer game programmers that place maximizing profits and growth above the love and fun of writing great games – these are the people who are unknowingly bringing us to the edge of the abyss.

Why Mac?

Why Mac? says Apple’s new Special message to Windows users: Welcome.

Macs have many advantages: ease of use, integration of OS and hardware, reliability, overall lower cost of ownership over the life of the machine, and, of course, style.

Windows machines have advantages, too, such as more configuration options, cheaper up front cost, availability of software, snappier response on window controls, cheaper components, more peripherals.

That’s an important thing to understand if you’re a Mac advocate. That’s why many of us call it the Good Fight. That’s why evangelism refuses to die, even though Steve Jobs himself tried to kill it (which may have been a simple strategic move, given Apple’s recent signs of standing up for itself).

Do the Right Thing

I fixed a couple of computers for people yesterday. My student assistants like helping fix computers, because they get to tinker and learn a bit.

“What do I owe you,” the owner said.

“Well, my students did all the work, ask them.”

We did, and the young man said, “No charge. It was fun.”

We Mac users need to stick together. It’s important.

It’s important to support Linux efforts as well.

Why?

Because it’s the right thing to do.

Further Reading

- Learning the lessons of antitrust history, Ephraim Schwartz and Ed Scannell, InfoWorld

- Federal judge rules Parker Brothers holds Monopoly monopoly, The Onion

- Anti-Monopoly, Anti-Monopoly, Mary Bellis, About.com

- “Boss Tweed” and the Tammany Hall Machine, David Wiles

- Boss, Smithsonian Magazine

- Whatever happened to Standard Oil?, US Highways

- The Rockefellers, The American Experience, PBS

- The Lessons of the AT&T Breakup, BusinessWeek

Monopoly® is a registered trademark of Hasbro, Inc.

Keywords: #monopoly #microsoftmonopoly

Short link:

searchword: monopoliesarebad