Apple was at an all-time low in 1996, in a severe financial crisis that worried Mac users around the world. Apple’s shareholders and customers were losing faith, and competitors were closing in fast. The worldwide press badmouthed Apple in 1995 and 1996.

Today Apple is a completely different company. I’m going to analyze how Apple got into trouble and how they climbed back to become “insanely great” once again.

How the Trouble Started

By 1995, Apple was an incredibly healthy business with impress figures to boast. They shipped 1.3 million Macintoshes and generated $3.1 billion revenue from the quarter ended in December 1995. Unit sales of Macintosh software increased by 26.9% for the first ten months of 1995. Apple had impressive market share figures amongst US K-12 institutions and the creative professionals market, including graphic and Web designers.

But 1995 wasn’t all that great. In August 1995, the PowerBook 5300 was released. It was the first PowerPC-based PowerBook, and it was a much anticipated product. Apple arranged for product placement in the two biggest blockbusters of 1996, Mission: Impossible and Independence Day.

But 1995 wasn’t all that great. In August 1995, the PowerBook 5300 was released. It was the first PowerPC-based PowerBook, and it was a much anticipated product. Apple arranged for product placement in the two biggest blockbusters of 1996, Mission: Impossible and Independence Day.

Little did Apple know how much this would further disadvantage their reputation. Many of the first few units shipped were dead on arrival. Furthermore, there were issues with the Sony-made lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries bursting into flames. Apple had to recall the entire product line, even though not a single battery ever caught flames outside of the company.

The PowerBook 5300 also shipped with buggy system software, and it didn’t include a Level 2 cache, negatively affecting performance. There were also problems with several components that Apple addressed through a repair program that continued for seven years.

After the 5300 fiasco, Apple lost market share in laptop computers, and their reputation was damaged – for a while at least.

Mac Clones

In 1995, Apple began the Macintosh clones program where, in an attempt to gain market share, Apple licensed the Mac OS to third party hardware vendors such as Radius, Power Computing, Motorola, DayStar, and Umax.

The Power Computing clones were the fastest personal computers in 1996, and that affected Apple’s Power Macintosh sales due to their aggressive pricing. In a December 1995 issue of TheMac in the UK, a Power Computing 120 MHz Mac OS-compatible tower cost £1,899 ($3,344). At the same time, the 120 MHz Power Macintosh 9500 cost £3,725 ($6,560). Although Power Computing claimed to be “fighting back for the Mac”, they were in fact killing Apple. Apple’s Mac sales started to drop.

The Power Computing clones were the fastest personal computers in 1996, and that affected Apple’s Power Macintosh sales due to their aggressive pricing. In a December 1995 issue of TheMac in the UK, a Power Computing 120 MHz Mac OS-compatible tower cost £1,899 ($3,344). At the same time, the 120 MHz Power Macintosh 9500 cost £3,725 ($6,560). Although Power Computing claimed to be “fighting back for the Mac”, they were in fact killing Apple. Apple’s Mac sales started to drop.

The clone programme ultimately lost money for Apple and the participating third party vendors. Michael Spindler was ousted as CEO and replaced by Gil Amelio in 1996 to give Apple the guidance it desperately needed.

‘A Huge Mess’

Amelio was placed in the center of a huge mess and told to sort it out. He wrote a strategy for Apple and pointed out the major problems. He concluded that Apple had a shortage of cash and liquidity, low-quality products, lacked a viable operating system strategy, had an undisciplined corporate culture, and was trying to do too much and go in too many directions.

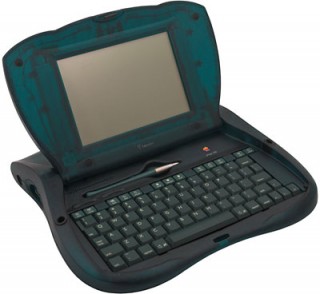

Amelio started to address these problems by cutting Apple’s costs. He reduced the workforce by thousands and discontinued the Copland operating system project. However, Amelio did not discontinue the Newton family of products; additionally, the eMate 300 Newton laptop was released under his reign at Apple, one of his mistakes.

Amelio started to address these problems by cutting Apple’s costs. He reduced the workforce by thousands and discontinued the Copland operating system project. However, Amelio did not discontinue the Newton family of products; additionally, the eMate 300 Newton laptop was released under his reign at Apple, one of his mistakes.

Apple’s Savior

Amelio is greatly undervalued, because he ultimately saved Apple by purchasing NeXT for $402 million from Steve Jobs, Apple’s cofounder, on February 4, 1997. Amelio had considered purchasing Be, Inc., which had asked for $400 million, but Amelio was affected by Jobs’ Reality Distortion Field.

Many overlook Amelio’s decision to purchase NeXT, but it was a vital turning point in Apple’s history because it brought Steve Jobs back to Apple as a consultant in 1997.

On July 26, 1997, Mac OS 8 was released in an effort to keep the Mac OS alive. It was very successful, exceeding Apple’s sales expectations fourfold. 1.2 million copies were sold in the first two weeks, growing to 3 million within six months. At Macworld Expo Boston 1997, booths selling Mac OS 8 sold out.

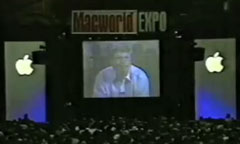

Steve Jobs addressed his own keynote at the Macworld Expo event in Boston, outlining Apple’s plans and introducing new board members (mostly his close friends from the board of NeXT). Jobs talked about Apple’s strong brand, education market share, and assets, such as the Mac OS.

An Olive Branch for Microsoft

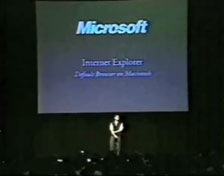

At the keynote, he also announced a five year partnership with Microsoft including cross-licensing of patents, bundling Internet Explorer as the default browser on new Macs, an agreement that Microsoft would continue to develop and support Microsoft Office for the Mac for at least another five years, collaboration on Java, and Microsoft’s investment of $150 million in Apple stock, which they could not sell for three years.

In addition, Bill Gates appeared on the keynote screen over a live video feed – and the audience’s response was priceless. They laughed, booed, and even had their cameras out for several seconds while Bill Gates grinned at everyone.

The renewal of the Microsoft partnership was certainly a good decision; Apple had been disrespectful towards the very companies that were helping them survive during their most difficult times.

The renewal of the Microsoft partnership was certainly a good decision; Apple had been disrespectful towards the very companies that were helping them survive during their most difficult times.

Microsoft and Apple first worked together in the 1970s when Microsoft licensed a version of BASIC to Apple, which modified it for the Apple II. In 1984, Apple and Microsoft joined in an effort to bring the first productivity and office applications to the original Macintosh. Microsoft shipped Mac versions of Word and MultiPlan (later Excel), becoming Apple’s unique selling point for the Macintosh during its growth.

Ever since Windows had been released, Apple’s employees and their customers had been in an ongoing war with Microsoft. In 1997, Jobs decided to end this war by treating Microsoft better and telling the audience at his keynote that the battle between Apple and Microsoft related to their operating systems was over.

Apple’s Most Important Asset

Another thing Jobs mentioned at his keynote in 1997 was the Apple brand and how it is Apple’s most important core asset beside the Mac OS. During the 1980s and 1990s, John Sculley, then Apple CEO, built up Apple as a solid brand in the business world, and this became a very important asset to Apple.

Though the Apple brand was an important asset, Apple took it for granted in those days. The Apple brand was (and still is) extremely well recognized, with credit due to their advertising campaigns for the Power Macintosh, Newton family, and Performas during the 1990s under John Sculley – and brand loyalty was also strong with 25 million Macintosh users in 1997.

On October 6, 1997, Michael Dell, CEO of Dell, said during a keynote to several thousand IT executives that he would “shut [Apple] down and give the money back to the shareholders” only a week after Steve Jobs addressed his keynote outlining Apple’s latest strategies to become a healthy company again. Dell’s comment was generally considered as a blatant, unthoughtful take on what to do with Apple.

Many others were doubtful of Apple’s future at the time – many in particular thought Apple would have difficulty recruiting a new CEO because of Jobs’ presence at the company.

Rumors were also circulating that Apple would use Windows NT on its upcoming network computers.

Getting Back into Business

Apple lacked a “clean” and logical product family of computers in 1997. Jobs himself explained at the Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC) 1998 keynote that Apple’s prior product line was confusing to the market and expensive for Apple. There were too many models, and they were often priced wrong and aimed at the wrong markets.

Consumers were confused and never knew what to buy. Why should I buy a 9500 instead of a 9600 or an 8200 instead of an 8500? Nobody knew; even Apple’s salesmen couldn’t explain to customers which they should buy.

Much of this product confusion was created by Michael Spindler during 1993-1996 period when he created a large product line of Macintosh Performas, a consumer line which over time became more and more confusing to consumers.

To address this problem, Jobs decided to streamline Apple’s product line into two categories, each with its own two categories. There are two markets for computers – consumer and professional – and both need desktop and laptop models.

The Power Macintosh G3, available in desktop and minitower versions, was released in November 1997 as the pro desktop Mac, and the PowerBook G3 (Kanga) was the pro laptop Mac.

On July 15, 1998 Apple reported its third profitable quarter since Jobs returned, earning $101 million in good part due to 750,000 Power Mac G3 units sold since it’s introduction.

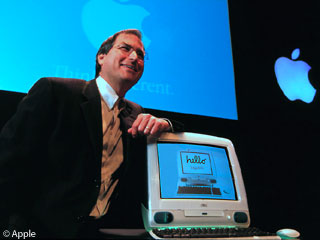

The iMac

Jobs knew that in order to experience further growth, Apple needed to create a product that consumers wanted, one that would appeal to the mass market. The Macintosh Performa series had been discontinued and needed a better replacement.

Thus, the iMac was born, a desktop Macintosh similar to the original Macintosh 128K in many ways. The iMac was a 233 MHz All-in-One desktop with built-in networking, two 12 Mbps USB ports, and a futuristic translucent Bondi blue colored case designed by Jonathan Ive.

Thus, the iMac was born, a desktop Macintosh similar to the original Macintosh 128K in many ways. The iMac was a 233 MHz All-in-One desktop with built-in networking, two 12 Mbps USB ports, and a futuristic translucent Bondi blue colored case designed by Jonathan Ive.

Jobs realized the potential of Johnathan Ive, a member of Apple’s industrial design team who had joined the company in 1992. Ive had previously designed the Newton MessagePad, eMate 300, and the Twentieth Anniversary Macintosh. He was chosen to design the iMac and came up with hallmark design that distinguished it from any other personal computer, using bright colors and a simplistic, user-friendly appearance.

The translucent Bondi blue case appealed to customers, and the iMac became an instant hit, selling 800,000 units in 1998 (a rate of one sold every 15 seconds). CompUSA’s executive vice president of merchandising said, “The launch of the iMac was the largest-selling day of any given computer we’ve ever had.”

The iMac was announced in May 1998, priced competitively at US$1,299, and began shipping in August 1998. Development of the iMac is said to have begun the day Steve Jobs returned to the company, because he noticed Apple did not have a compelling consumer Macintosh priced under US$2,000, which he said was “really scary”.

Next: Apple’s Climb Back to Success

References

- Apple Confidential 2.0, Owen W. Linzmayer

- Infinite Loop, Michael Malone

- Wikipedia