Extreme Tech’s Sebastian Anthony says that Thunderbolt, which Apple introduced earlier this year, is already dead in the water. I beg to differ.

Sometimes Apple has a better idea that the rest of the industry ignores, and it’s usually a simpler solution than the PC world embraces.

Early Mac Standards

Apple Desktop Bus (ADB)

For instance, Apple invented ADB, the predecessor to USB, and started using it with the Apple IIGS in 1986 – and on the Mac II and Mac SE when they were introduced in early 1987. With ADB, the same port could be used by a mouse, a keyboard, or even a modem. At 10 Kbps, it wasn’t fast, but it was plenty of speed for keyboards and mice.

On the PC side, there were parallel ports for printers and RS-232 serial ports for modems, as well as for a wide range of other devices. Parallel ports used a huge 25-pin connector, as did the original PC serial port, although the industry eventually moved to the 9-pin DE-9 serial port. Two protocols, two types of cables, two different connectors.

Mac Serial Ports

Apple adopted RS-422 serial ports and began using a Mini DIN-8 port with the Mac Plus in January 1986. From 1987 until 1998, most Macs shipped with one or two ADB ports and two Mac serial ports, which have a bandwidth of 230.4 kbps. You could connect a printer, modem, or other serial device to either port – and you could even use the one marked with a printer icon for LocalTalk networking. (This was years before ethernet became popular.)

SCSI

While the PC industry tried to settle on a hard drive standard, Apple embraced SCSI, again starting with the 1986 Mac Plus. One SCSI port can support up to seven SCSI devices – hard drives, scanners, printers, tape drives, SyQuest drives, etc. SCSI remained standard on most Macs until 1998, when Apple began to use USB 1.1 with the original iMac.

Ethernet

When LocalTalk speed became a bottleneck, Apple began including 10 Mbps ethernet ports on Macs, starting with the Quadra 700 and 900 in 1991. Ethernet soon became standard across the line, and the only Macs today without built-in ethernet are the 11.6″ and 13.3″ MacBook Air, which just don’t have room for it. Ethernet has gone from 10 Mbps to 1,000 Mbps over the years, but despite speed changes, it remains an enduring protocol.

GeoPort

Apple introduced a faster 2 Mbps serial port, the GeoPort, with the Centris 660av and Quadra 840av in 1993. The faster GeoPort was completely backward compatible with the older port, and most users never knew there was a difference. As with ethernet, the change was transparent to the end user.

Embracing PC Standards

Apple began to use industry standard IDE hard drives starting with the PowerBook 150 and Quadra 630 in 1994, although these models also included full SCSI support. By using IDE, Apple was able to use less costly drives and make Macs a bit more cost competitive with PCs. The SATA drive connector found in today’s Macs is a direct descendant of IDE, although with a completely different cabling system and higher bandwidth. (Apple began to use SATA with the Power Mac G5 in 2003.)

Although there were some compatibility issues, especially regarding maximum drive capacity, for the most part IDE (also known as ATA, Ultra ATA, and Parallel ATA) remained transparent to the end user, and the same is generally true of SATA as well.

Apple also began to use PCI expansion slots in 1995, another example of it embracing an established industry standard from the PC world.

The Next Generation of Ports

USB

With the iMac, Apple adopted the relatively new USB port to replace the ADB, serial, and SCSI ports found on previous Macs. The USB 1.1 specification supported low-speed (1.5 Mbps) and full-speed (12 Mbps) devices, and the iMac actually shipped a month before the 1.1 specification was finalized. From that point forward, all wired Apple mice and keyboards would use USB.

USB was fine for low-speed devices like keyboards, mice, and printers, adequate for slow CD-ROM and CD-RW drives, but way too slow for hard drives. Having only USB ports was okay for the consumer market, but power uses needed something much faster. After all, the Beige Power Mac G3 already had 80 Mbps (10 MBps) Fast SCSI and 133 Mbps (16.67 MBps) IDE busses, and they didn’t want to go backwards.

FireWire

Apple’s better idea was FireWire, which was a 393.2 Mbps (nominally 400 Mbps) protocol. FireWire came to the Mac in January 1999 with the Blue & White Power Mac G3, which was also the first Power Mac with USB. Although FireWire was an industry standard (IEEE 1394), it wasn’t widely used outside of Macs and camcorders.

The Blue & White G3 also supported Ultra ATA, a 266 Mbps/33 MBps step up from the IDE bus found in the Beige G3. The Mac now had an external data bus faster than its hard drive bus!

Undermining FireWire

Greed

Two things happened to prevent the widespread adoption of FireWire. Apple got greedy, seeking a $1 per port royalty for devices that used its technology, and USB 2.0 was just around the corner. Although Apple changed its mind on royalties, it left a bitter taste among those who were prepared to embrace FireWire.

USB 2.0 Competition

And then USB 2.0 arrived in 2000, with a 480 Mbps bandwidth and no additional royalty costs over those already being paid for USB 1.1 ports. Although USB 2.0 couldn’t match the real world throughput of FireWire 400, it didn’t really matter. The PC industry embraced USB 2.0 and generally ignored FireWire, while Apple did its best to push FireWire with its early FireWire-only iPods.

Apple finally adopted USB 2.0 ports with the Power Mac G5 and the third generation iPod in 2003. Although FireWire has never disappeared from the Macintosh line, the iPod stopped using FireWire to sync with iTunes with the 2005 fifth generation iPod.

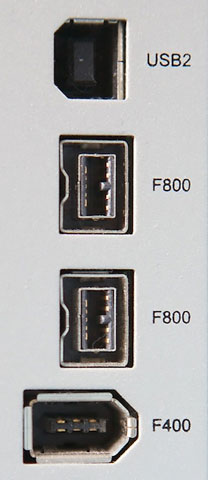

FireWire is great for connecting external drives, and FireWire Target Disk Mode can be a great tool for installing software or migrating user data between machines, but Apple made one big mistake when it made FireWire faster: FireWire 800 was introduced with a completely new connector incompatible with FireWire 400 cables.

The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same

With Apple serial ports, ethernet, SCSI, IDE, and USB, speed upgrades had pretty much been transparent to the end user. The connectors remained the same, and backward compatibility wasn’t an issue.

If Apple had continued to use the same FireWire connector when it introduced FireWire 800, FireWire might have had a very different future. Instead, Apple created an unnecessary gulf between older hardware and newer hardware. Although FireWire 400 devices are 100% compatible with FireWire 800, you need a special cable or port adapter, and as Apple has now moved all Macs to FireWire 800, migrating FireWire 400 peripherals to FireWire 800 Macs is an extra expense that just grates on longtime Mac users.

Had Apple retained the same port, we’d probably have seen the industry move forward with FireWire 1600 and 3200 hardware by now. Instead, today’s Macs are still using FireWire 800 ports, not something faster.

USB 3.0 or Thunderbolt?

We’ve picked on Apple for introducing new Macs without USB 3.0 after the faster protocol – ovre ten times as fast as USB 2.0 – was finalized, and we still think it would have been a great feature for the MacBook Air, as it only has USB ports. But just as Apple dragged its feet on USB 2.0 while trying to expand the FireWire 400 base, Apple seems to be in no hurry to embrace USB 3.0.

Once again, Apple has a better idea. Where FireWire started out as a bus over 30x faster than USB 1.1, only to be eclipsed by USB 2.0, Thunderbolt (a technology pioneered by Intel) has over twice the bandwidth of USB 3.0, 20 times the bandwidth of USB 2.0, 12 times the bandwidth of FireWire 800, and 1.6 times the bandwidth of 6 Mbps SATA Rev 3. There’s no USB 4.0 around the corner to eclipse it, so it should be the fastest protocol for a few years at least. [Editor’s note: In 2013, 10 Mbps USB 3.1 and 20 Mbps Thunderbolt 2 were introduced, doubling the speed of both protocols and still retaining Thunderbolt’s advantages.]

Apple has worked to avoid introducing a new port by using the same connector as the Mini DisplayPort. It can do that because Thunderbolt is so versatile that it can transmit video and support PCI Express devices. New Macs are gaining Thunderbolt Target Disk Mode, which should make migrating from one Thunderbolt equipped Mac to another lickety-split fast.

To top it all off, Thunderbolt can support USB 3.0 adapters, making it easier for Mac users with 2011 Macs to use USB 3.0 devices should they have the need.

But perhaps the biggest reason of all that Thunderbolt will succeed is that it has the full weight of Intel behind it. Although Apple was the first to build in Thunderbolt, we can expect it to appear on high-end PCs in 2012.

I’m pretty certain Apple and Intel won’t make the FireWire mistake and switch to a completely different physical connector if or when a faster version of Thunderbolt arrives.

Besides which, USB 3.0 has its own connector problem. Although USB 3.0 devices will connect to USB 2.0 ports and USB 2.0 devices will connect to USB 3.0 ports, both using standard USB cables, USB 3.0 devices will only achieve USB 3.0 speed with USB 3.0 cables. Ditto for USB hubs – if they’re not USB 3.0, you’ll only get USB 2.0 throughput when you connect USB 3.0 devices.

Thunderbolt is new and making its way in the world, and it’s anything but dead in the water. It’s going to be with us for years to come.

Short link: http://goo.gl/wgI1El

searchword: firewirefailed

How does ðis feel four years later?

Until USB 3.1 and the USB-C connector, Thunderbolt looked like the future with its higher throughput, less OS overhead, ability to provide lots of power to devices, and reversible connector. It is still superior for certain purposes, but I suspect the 12″ MacBook marks the beginning of the end for Thunderbolt on consumer Macs. Assuming the MacBook Air isn’t phased out, expect it to be the next to go USB-C only.