Like many of you, I work amongst a combination of Macs and Windows

PC (and with at least some users who want to try out Linux). In my

case, it's at an elementary school. Schools tend to collect a

hodgepodge of hardware including different platforms from different

eras.

Ideally, we would like the kids to be able to do the same work no

matter what computer they're sitting at, so cross-platform software is

a big plus.

A while ago, a grade 3 (as Canadians put it - only Americans say

"3rd grade") teacher asked a simple sounding question: "Is there

anything my kids can do on the computer that will help them learn to

work with money?"

One of the skills that adults take for granted is knowing that four

quarters make a dollar and that two fives is the same as one ten dollar

bill. Kids have to learn this.

There's a nice website: Change Maker, that

supports US, Canadian, Australian, UK, and Mexican currency, but

frankly, it's a bit too hard - kids have to mentally do a fairly

complex subtraction and then click on pictures of various kinds of cash

to indicate the right answer.

Talking to the teacher, she wanted something simpler, something that

gave kids an amount and asked them to show the kinds of money they

would use to reach that amount. As I checked around with different

early grade teachers, something like that seemed potentially useful,

but with various levels. The grade 1 kids needed to work with small

change, up to a dollar or so. By grade 3, they needed to be comfortable

with amounts up to about $100. And, of course, being in Canada, we

needed something with Canadian currency, not American.

Some History

Step back a couple of decades to the early years of personal

computing. When Time Magazine declared the personal computer its

"Machine

of the Year" in its 1983.01.03, there was a concept known as

"computer literacy." There wasn't much prepackaged software available

yet, and any self-respecting personal computer user of the late 1970s

or early 1980s had to expect to be able to make their own.

For most personal computers, that meant a familiarity with the BASIC

(for Beginner's All Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) computer

programming language, which was originally developed in 1964 at

Dartmouth University by John Kemeny and Thomas Kurt as a teaching tool.

Steve Wozniak developed a version of BASIC for the Apple II computers,

and Microsoft got its start peddling BASIC variants for most of the

other personal computers of the era. (Little-known fact: IBM originally

contacted Microsoft to license Microsoft BASIC for its then under

development IBM PC; they only licensed the operating system that became

known as MS-DOS after failing to reach agreement with Digital

Research.)

When the Mac was released in 1984, there was a Microsoft BASIC for

it, too. But standard BASICs were not a good fit for the graphical,

windowed, mouse-driven Mac environment; they were designed for an

earlier era of text-based terminals. And much of what made the Mac

Mac-like was buried deep in Apple's Toolbox code; it was possible to

access it with MS BASIC, but it wasn't fun or easy.

Graphical environments like the Mac OS or MS Windows make life

easier for users but harder for programmers. And BASIC was getting a

bad rep. Many programs made a lot of use of GOTO statements for jumping

around to different parts of the code; programming professionals

derided this as "spaghetti code," a tangled mess that was hard to

follow.

With the increasing availability of commercial software, there was

less need to write your own code to get your work done. And just as

people can learn to drive a car without having to become auto mechanics

few computer users saw any need to learn to program their own

computers.

Apple's 1987 release of HyperCard

was a step towards changing this, a way that nonprogrammers could

create graphic and friendly computer applications. But while the Mac

version was wildly popular, similar programs failed to catch on amongst

PC users running DOS or Windows. Instead, Microsoft went back to its

roots in 1991 and released Visual Basic, initially with versions for

Windows 3.0 and DOS.

Visual Basic simplified program development for graphical

environments by including an environment similar to a desktop

publishing program; users could create an interface with windows,

buttons, and standard controls without having to program them from

scratch. Controls could then be attached to BASIC code, modernized to

do away with those ugly GOTO statements, but including modern

subroutines and modules.

Visual Basic (VB) was a big hit; it unleashed thousands of wannabe

programmers, and the resulting flood of VB applications (covering the

full range of good, bad, and indifferent) played a roll in making

Windows massively popular. It's no surprise that Microsoft kept later

versions of VB Windows-only (though the related Visual Basic for

Applications is used as a macro language in Microsoft's Mac Office

versions).

Enter REALbasic in

the late 1990s. REALbasic started life as a Mac-only Visual Basic

look-alike; a similar drag and drop environment for creating user the

user interface, and similar modernized BASIC-style code behind the

scenes.

In fact, REALbasic includes the ability to import Windows Visual

Basic project code, and, with a bit of massaging, use it to produce

Mac-usable programs.

Disclaimer

I am not now and have never been a programmer. Over the decades,

I've dabbled a bit in writing code in BASIC. For instance, on my

website, you can download copies of a BBS-simulator that I wrote long

ago for my school district, letting classes simulate the experience of

logging on and poking around the BBS that the Vancouver school system

ran for educational use. At a time when a school was lucky to have one

computer connected to a phone line for online activities, this let a

lab-full of students get a taste of being online. There's even a

version in MS Macintosh Basic. (I just gave it a try, and it mostly

works in Classic mode on my Panther-powered system: www.zisman.ca/files/Ed-Net.sit).

While I've done some work with Visual Basic, and now with REALbasic,

I'm nowhere near a guru with any of these development environments.

There are lots of helpful REALbasic resources online, starting with,

but not limited to, REALsoftware.com.

Back to BASICs

Like Visual Basic, REALbasic is extensible; third-parties can add to

its capabilities with plug-ins. As a result, would-be programmers don't

have to reinvent everything from scratch. If a feature isn't already

built-into REALbasic, there is often a plug-in available that already

provides the feature you need. A quick search for "REALbasic" at

Versiontracker.com, for

instance, listed 132 downloadable plug-ins, many free, others shareware

or commercial.

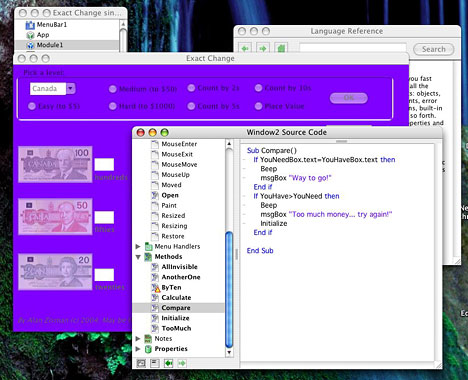

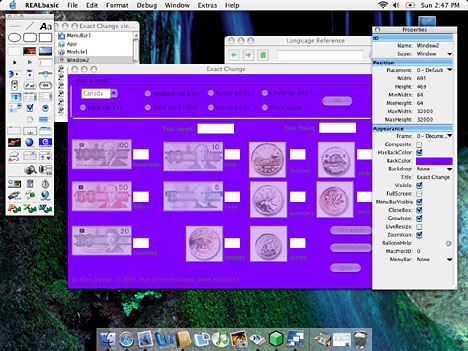

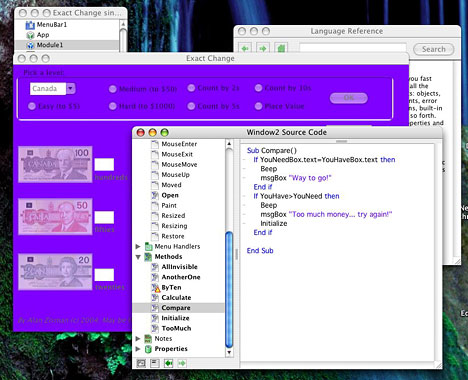

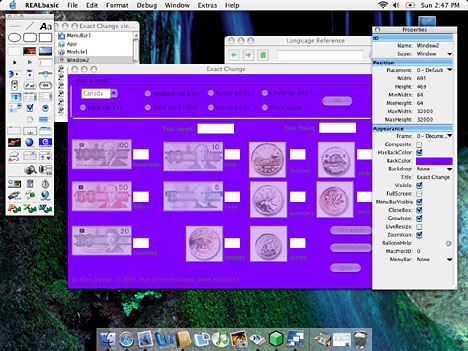

Coding Exact Change

As REALbasic evolved (it is currently up to version 5.5), it added

support for the Internet and for media types including sound and video.

But more importantly for my purposes, it became cross-platform.

Relatively early, REALbasic users on the Mac were able to create

Windows applications! Later versions supported both Mac Classic and

OS X environments. Still later, REALsoftware released a companion

Windows version - this version can load projects created with the Mac

version (and vice versa), though some third-party plug-ins may only run

on one platform or the other.

Currently, REALbasic 5.5 comes in Mac Classic, Mac OS X, and

Windows versions. The Professional edition of any of these versions can

compile code into programs for Mac (Classic and OS X), Windows,

and now Linux as well. (The Standard edition can only create

applications for the OS it is running on).

For me, that's a killer feature - the ability to code something once

and then compile it so that it will run everywhere.

"Write once, run everywhere" is the promise of the Java programming

language, but Java programs have tended to look ugly and run slowly,

dependent on the quality of a virtual machine for each operating

system. Compiled REALbasic programs run quickly and use the standard OS

widgets and components for each operating system; the Mac OS X version

gets rounded, glowing buttons, while the Windows versions gets

Windows-native buttons.

It Don't Come Easy

There's still a learning curve. My 1980s-era BASIC background has

some carry over; I can write IF-THEN-ELSE statements and DO-UNTIL

loops, but I'm still fuzzy on a lot of concepts. (Thanks to fellow

Vancouver teacher and Duet

Software programmer Peter Findlay for getting me through a

number of rough spots).

You can look at the current version of my money program, Exact Change, in

Mac OS X, Mac Classic, Windows, and Linux versions, since it was

built with REALbasic.

Exact Change

One of the things I've realized: Computer programs are never

finished. Aside from getting the obvious bugs out, every version leads

to ideas for how to go further. The original Exact Change evolved into

a version with different levels for kids in grades 1, 2, and 3. Then it

grew to offer practice using money to help count by 2s, by 5s, and by

10s, and to help learn place value.

The current version uses Canadian currency. I would like to

internationalize it and let users choose US currency - or Australian or

British. I would like to be able to print out the students' work.

To do those things, I'm going to have to learn more about working

with REALbasic.

But another thing I've realized: Creating computer programs is

addicting. Like many computer games, there's a real rush when something

works. And there are a lot of dead ends. But I'm finding myself

thinking of strategies and planning modules and trying to squeeze in

time to just add one more feature.

Getting REALbasic

A full version of REALbasic (Classic, OS X, or Windows) can be

downloaded from www.realsoftware.com; potential

users can register with REALsoftware and receive a license key that

enables the downloaded program to work for 10 days. (The trial period

can be extended for an additional 10 days). Programs created during the

trial version will run for 15 minutes and then shut themselves

down.

REALsoftware sells the software in a variety of packages, both

downloadable and physical. A Standard license (US$100) can be used with

one downloadable copy of the Standard edition. A physical copy

(included printed documentation) starts at US$150.

The cross platform-capable Professional edition costs US$400 for a

download license, US$450 for a physical copy. Academic pricing (with

proof of academic status) is about 30% cheaper.