This is our third and final look at Henry Bortman’s “Macintosh 2000” predictions in the March 1992 issue of MacUser.

Back in March 1992, MacUser magazine ran an article comparing past and then-current Macs. One comparison was the original Macintosh with the Quadra 900: 8 MHz 68000 vs. 25 MHz 68040, 128 KB RAM vs. 4 MB (expandable to 256 MB), no SCSI or hard drive vs. several internal drive bays and an external SCSI bus, etc.

The next question: what would the Macintosh be like in another eight years. Following are Henry Bortman’s speculations, followed by my comments (indented blue text). A few comments have been added in [square brackets] to show how close – or far off – Bortman’s predictions were.

Mac 2000

What will tomorrow’s Macs be like? Well, for one thing, they won’t be Macs. By the turn of the century, the Mac will be a museum piece. And so will the Mac operating system.

It’s well over eight years since Bortman wrote this. The Macintosh and the Mac OS have been through a lot of changes, especially moving to PowerPC in 1994. Despite moving through System 7 and Mac OS 8 all the way to 9.0.4, the OS remains familiar, as does the hardware.

Today’s Macs use PowerPC G3 and G4 processors at speeds ranging from 350 to 500 MHz. They’ll soon be running Mac OS X, a union of the Aqua interface with the power of a Mach kernel.

Those of us who stop using our old Macs may create display cases, personal museums for the Macs we knew and loved, but only because the new Macs are so much more powerful. The old Macs remain useful; they’re just slow. (I personally draw the lower limit of practicality at 16 MHz, although many low-end Mac users still love the 8 MHz machines.)

Not that there won’t be some familiar leftovers. You’ll still have icons on your computer screen, for those occasions when you insist on manipulating data manually. But voice commands will be more common. For graphics work, you’ll have a pressure sensitive pen.

Voice commands may be fine in a private office, but when I experimented with it on a Quadra 660av several years ago, people in adjoining cubicles voiced their complaints. Voice technology is fairly well developed now, but it is likely to remain a niche input method for the next few years.

As for pressure sensitive pens, they really haven’t made inroads yet, despite the fact they keep getting smaller and more affordable. The Palms do a good job with handwritten input, and they have become the mainstream PDA.

Until we have affordable high resolution workslate screens, pressure sensitive pens will remain the domain of the graphics professional with a touch tablet. But given a few more years, it could become a reality for the rest of us. Rumors are Apple may even incorporate such a technology into a trackpad in coming years.

So far, these technologies remain promising, but they are not yet widely used on the Mac.

Networks will be pervasive, but wires will be antiques. Future Macs will communicate by radio waves, so you’ll be connected wherever you go. Your computer will also function as a telephone, fax machine, pager, mailbox, and interactive cable-ready television. Vast quantities of useful information will be instantly available on The Net – a universal hookup to the world’s libraries and databases.

Networking remains pervasive in the Mac world, but it also remains an extra-cost option for most Wintel computers – although there are signs that’s starting to change. Radio waves are used in some locations where the cost of wiring is prohibitive, but have not caught on in general. AirPort is changing that, but it won’t be a pervasive technology for another year or so. As wired networks move from 100 Mbps ethernet to gigabit ethernet, expect something faster than 802.11b AirPort within the next year or two. [802.11g arrived in early 2003 at 5x the speed of 802.11b.]

Infrared connectivity seems to have discovered a niche for beaming files between Palms, but due to line-of-site constraints is not really practical for computers. AirPort and similar wireless networking schemes have almost made IR obsolete already.

On the other hand, there are cellular modems, allowing connection to the internet from anywhere with cellular phone service. It’s far from cheap, but it is a viable option for some users.

The whole issue of the computer as telephone has become tied in with use of the internet to make free (or minimal cost) phone calls anywhere in the world. It’s become a regulator’s nightmare as the phone companies try to control a technology they never anticipated. And now we have the phone as PDA and web browser.

The computer as fax machine is a reality. At work, I used to send most faxes from my Power Mac to a LaserWriter 16/600 with a built-in fax card (alas, this is no longer supported under OS 9). It dials the phone and sends the fax, which frequently goes right to another computer, where it is only printed out if a hard copy is needed for billing purposes (most of my faxing is purchase orders). It sure beats printing, grabbing a sheet of paper, and then walking to the fax machine. You can do the same kind of thing with a fax modem, so score one for Bortman.

Computer as pager? Not the Mac – that’s a PDA function. The Palm and Pocket PC machines already offer this. Expect it to be normal on portable computers in another year or two, so two more points for Bortman.

The computer really hasn’t shown itself a strong contender to replace the television. There are TV cards, AV inputs, and DVD players, but television does a much better job of displaying TV programs than the computer – and at a for more realistic price. As computers increase in power, this will become more viable, but it will still be less practical than regular TVs for regular television watching.

On the other hand, thanks to Apple and others, DVD has gone from an odd accessory to a staple. Except for the 366 MHz iBook and two least expensive iMacs, every current Mac has DVD as an optional or standard feature. PowerBook and iBook SE users love watching their favorite movies on their computers, so let’s give him a half-point here.

Finally, score a big one for Bortman on predicting the widespread deployment of the Internet. It’s not quite what anyone envisioned in 1992, but the World Wide Web has become so pervasive in the past four years that we look askance at people without email or businesses without Web sites.

By the way, an article on the Internet in the February 1992 issue of BYTE mentions email, Anarchie, FTP, and a few other things – but the World Wide Web didn’t even exist when Bortman made his predictions.

You won’t buy applications for your Mac either. You’ll buy functional modules. You’ll be able to assemble them as you do Lego building blocks, to perform precisely the tasks you require. You will train them by performing a task once and telling your Mac to remember how you did it. Of course, all documentation will be on-line, including interactive video tutorials.

Apple and Microsoft invested many years and millions of dollars in this idea. Apple’s OpenDoc never really cut it (don’t tell CyberDog lovers!). Microsoft’s OLE didn’t fare much better. We still use the same of paradigm of documents being tied to programs.

Microsoft Office is probably the most successful family of programs to provide tight integration, allowing users to paste an Excel spreadsheet into a Word document – and use it live, just as if they were running it in Excel.

On the Mac side, I and many others have been spoiled by the program that dethroned Microsoft Works. AppleWorks (formerly ClarisWorks) brought a new level of integration to word processing, spreadsheet, database, and graphics modules. In fact, ClarisWorks 1.0 was reviewed in the same issue of MacUser as Bortman’s Mac 2000 article.

For better or worse, software is coming with skimpier manuals and more exhaustive online help. As one who likes to sit down with a manual, a highlighter, and PostIt notes (for use as bookmarks), I don’t see it as a step forward. On the other hand, for those comfortable with online documentation, it means never misplacing your manual. (And it provides a natural market for third-party books, such as the ubiquitous Dummies series.)

Software is more integrated than it used to be, but not as modular as Bortman predicted. I don’t foresee that changing soon, if at all.

However, there is one huge exception: the browser. Growing from early programs that could simply display HTML properly and send email replies, they have grown into behemoths – each browser grows in functionality with each additional plug-in. (Even the svelte iCab gets a bit larger with each update.)

Perhaps this isn’t quite the way Bortman envisioned modular programming, but that’s really what Internet Explorer and Netscape Navigator have become. So with that and online documentation, score two more for the prognosticator.

You won’t have to worry about document formats either. Format translators, when necessary, will automatically ensure that the information you need will be presented properly, regardless of how it was created.

Again, there have been some solid attempts in this direction, but we’re still a ways off. Apple and Claris pushed XTND – until programs started using features it didn’t support. Apple used to bundle MacLink Plus converters with the OS, and Claris bundled it with some programs, but that was generally not transparent. The program would usually ask which converter you wanted to use.

Still, thanks to XTND and MacLink, documents are more easily shared between programs and across platforms.

Microsoft is pushing HTML as a universal document format, allowing users to save (or perhaps export) Excel spreadsheets and Word documents in the language of the Web. How this will work out remains to be seen, but it has strong potential. And, of course, Word and Excel files are now compatible across platforms. [Microsoft used Office Open XML for its Word .docx, Excel .xlsx, and PowerPoint .pptx file formats.]

And Adobe’s PDF has become the format of choice for documents that have to look a certain way. Apple says this will be a native format in OS X. The files tend to be large, you need a memory hungry (but free) program to view or print them, and you can’t edit the files without a special program, but PDF is rapidly becoming the second language of the internet (still way behind HTML). We’ll have to see how easily PDF files can be opened in various applications when OS X finally ships.

You’ll still need to consider document formats, but much less than in the past. I’ll give Bortman one point here.

“Out of memory” errors will become a thing of the past. Base configurations will contain 128 megabytes of RAM. For additional storage, you’ll use removable solid-state RAM cartridges, the size of credit cards, that will hold as much as a gigabyte of data each.

Well, yes and no. Yes, the typical Year 2000 Mac has 64 or 128 MB RAM, along with a 6-40 GB hard drive and a DVD drive. Moore’s Law predicted 1 GHz CPUs for 2000. The G4 is still experiencing teething problems at 500 MHz, but AMD and Intel are racing past the 1 GHz mark.

We haven’t eliminated out of memory errors yet, although OS X will give us that next year. The key is better virtual memory, making the switch between RAM and drive space seamless and quick – as long as you have room on your hard drive, you’ll have memory available.

Especially since the first Power Mac shipped, virtual memory (VM) has become a practical way to expand the memory within a Macintosh. Apple recommends turning VM on and setting it to 1 MB over installed RAM. Not only does this provide a bit more memory, but through some magic I don’t quite understand, it allows a Power Mac to run programs using less memory – sometimes a lot less memory.

It isn’t magic, but it seems that way. There is a performance penalty, but it’s usually small if you’re not pushing the limits of your physical memory. The downside is that a few programs, and even some fonts, don’t work well with VM. My personal solution is to install more RAM and turn VM off. Another option is to use RAM Doubler, which emulates VM without using the hard disk. (On the other hand, with troublesome programs, RAM Doubler can suffer a worse performance hit than VM. Also, RAM Doubler won’t do you any good if you have 256 MB or more installed.)

The solution to out of memory errors it twofold. On the one hand, Apple needs a more robust VM implementation, which we will get with Mac OS X. By using the Mach kernel, Apple will be able to create VM as large as your hard drive.

Hand-in-hand with improved VM is smarter memory management. A clever program from Jump Development, RAM Charger, added dynamic memory allocation to the old Mac OS. In layman’s terms, RAM Charger launched a program with just the amount of memory it needed to run (and it tracked this each time you launched the program, learning as it went). Then, as the program needed memory to open, modify, or create documents, RAM Charger gave the program that much additional memory. Clever! (And smart enough that you can tell it not to RAM Charge programs like Photoshop or Netscape, which will grab all your memory if they have the chance.) RAM Charger may have died after Mac OS 8.1, but Mac OS X will do the same thing.

So two more points for Bortman, one for 128 MB standard RAM, and the other for the impending end of out of memory errors.

But what about solid-state RAM cards? They exist, but they are costly and haven’t caught on with mainstream computers. They are common in handheld computers and digital cameras. Most laptops have PC Card slots, allowing them to accept the same memory cards as the handhelds and some digicams.

But will they hit a gigabyte and become affordable this year? It doesn’t look like it right now (Compact Flash memory costs about $1,600 per GB – a whole lot more than any hard drive), but I’m not willing to say it won’t eventually happen. On the other hand, hard drive cost and capacity will probably always give it a significant advantage over any type of electronic memory. As for gigabyte memory this year, I’d have to say Bortman was too optimistic.

On the other hand, we’ve had some real storage breakthroughs that Bortman didn’t discuss in the Mac 2000 article. Floppies are pretty much obsolete, CD-ROM is standard on every computer that doesn’t have DVD, 100 MB Zip drives are the second most popular removable media drive, and 2 GB cartridges look to be the next hot area (Jaz, Orb, DVD-RAM).

No, they aren’t solid state memory cartridges, but I use a Zip drive to transfer files between work and home, just as I might have used a solid state RAM cartridge if they had become the norm.

Bortman saw higher capacity transportable media ahead, he just predicted the wrong medium.

You’ll be able to have your Mac at your desk if you need to, but you’ll be more likely to carry it in your shirt pocket. Some models will hang on the wall of your conference room, where the white board lives today. Pen-based models will replace the artist’s easel or the draftsman’s desktop.

Maybe Bortman read too much science fiction. 😉

Seriously, it was the 1984 novel, The Mote in God’s Eye, that introduced the idea of a handheld computer. From the early 1980s onward, the computer industry has been working to invent a viable handheld – and it’s getting closer all the time.

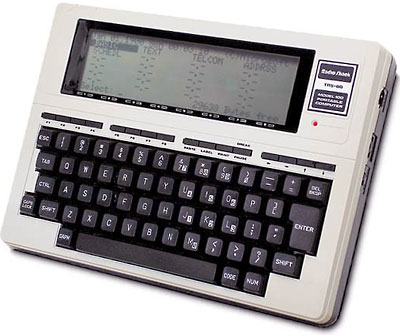

The first models were the Sharp PC-1211/Tandy TRS-80 Pocket Computer PC-1 (above) and Panasonic RL-H1400 HHC (for Hand Held Computer, and also sold as the Quasar HK 2600TE), with a one-line 24-26 character LCD display and a tiny keyboard. You could even program them in BASIC. Later came the Epson HX-20 (4 lines of 20 characters), the Radio Shack Model 100 (8 by 40), and other technological oddities.

Adam Osborne invented the transportable computer around 1980. Compaq made the first PC compatible version within a year of IBM introducing the PC. These were real computers, unlike the earlier handheld toys. And they were huge, about 40 pounds and the size of a suitcase.

Luggable gave way to lunchbox, gave way to notebook, gave way to laptop – which is where most of the portable computing power is today. The Pismo PowerBook G3 probably represents the best and biggest practical model today (any smaller and you’d have to sacrifice that killer 14.1″ screen).

But the real innovation is again in the handheld market. Apple’s Newton was a limited success, which Apple chose to sacrifice in favor of continued corporate existence.

Microsoft created Windows CE, which spawned an industry of handheld computers that would be immediately familiar to Windows users. Then came the Palm, which carved out a niche apart from Windows or the Mac OS – a niche which has grown to dominance in the handheld area.

But I don’t think we’re likely to see a handheld or shirt pocket Macintosh soon, if ever. Apple’s been through some rough times and still needs to focus on areas it knows, such as desktops and portables. Going once more into handhelds – at least until the company is firmly established on a solid financial footing – isn’t in the cards.

If Apple wants a presence, they need to license someone to produce a Palm OS machine with the Apple logo, bundle it with all the necessary cables and software, and sell it at a very competitive price. But I think Apple is too early in its recovery to do that today. [You could call the original iPhone, introduced in early 2007, a partial fulfillment of this prediction

What about white boards and pen-based LCD tablets? Count on them, but you probably won’t see the white board with an Apple logo. The tablet? We keep hoping, especially since some Wintel portables work that way, but no hints from Apple. [We had to wait until 2010 for the iPad – and 2015 for the iPad Pro, which supports a pressure sensitive stylus.]

Your computer display will be a full-color flat-panel LCD with a resolution of 150 DPI (dots per inch) or greater. Images will have the clarity of high-definition television. Printing will become a special-purpose activity; most information will be transferred electronically.

A couple years ago, I would have scoffed at the idea. Color LCDs were simply too expensive. Then I started reading reviews in PC Magazine and Macworld. Today’s LCD displays are high resolution (1024 x 768, 14″ to 15″) and several are now below US$1,000. IBM has 150 DPI screens and is working toward 200 DPI. We’re starting to see larger screens (up to 22″) with even higher resolution. The industry has created a standard digital interface for LCD monitors, which eliminates digital-to-analog conversion in your computer and analog-to-digital conversion in the screen – and further reduce prices. (Of course, Apple had to invent their own interface, but that’s another story.)

[Apple released its first Cinema Display in September 1999 with a 22″ 1600 x 1024 pixel display, but only 86 DPI. The Apple Cinema HD Display had a 23″ 1290 x 1200 pixel display at 98 PPI. The iMac G4 with its 15″ 1024 x 768 pixel flat panel display was released in January 2002. The first Apple device with a really high density display was the iPhone 4 with its 326 PPI Retina Display – in June 2010.]

[Apple released its first Cinema Display in September 1999 with a 22″ 1600 x 1024 pixel display, but only 86 DPI. The Apple Cinema HD Display had a 23″ 1290 x 1200 pixel display at 98 PPI. The iMac G4 with its 15″ 1024 x 768 pixel flat panel display was released in January 2002. The first Apple device with a really high density display was the iPhone 4 with its 326 PPI Retina Display – in June 2010.]

It’s very possible we’ll see $500 LCD monitors next year, along with larger ones we can hang on the wall for presentations or watching TV.

Printing will never become a special-purpose activity. Despite over a decade of pushing for a paperless office, it simply won’t happen. Hard copy is too important to abandon.

We have already reached the point where most information is transferred electronically. I get my news, values on my 401(k) plan, and mail electronically for the most part. Sure, I read magazines, but most of what’s in print I’ve already seen on the internet.

The Internet and World Wide Web have turned us into a highly wired society, probably much more so than almost anyone would have predicted in 1992. But Bortman definitely scores points for flat panel displays and electronic data transfer.

And price? You’ll be able to get a device with this “basic” capability for less than $1,000, allowing, of course, for inflation adjustments – but you’ll have to pay a bit more for the Holodeck option.

The last comment shows Bortman has at least one foot in the realm of science fiction. And wouldn’t we all love a Holodeck at the end of a long day at work? Computer, take me to Aruba.

But Apple finally has a pair of sub-$1,000 computers, the $799 iMac 350 and $999 iMac DV. Neither is a barn burner, but both are faster than any computer I use at home. The iMac line now makes up over half of Apple’s unit sales. The iMac is a lot of computer for the money.

As anyone whose been following this industry for more than two years can tell you, computers are a moving target. The same $1,300 that paid for my Centris 610 in 1993 (20 MHz 68LC040, 4 MB RAM, 80 MB hard drive, no CD-ROM, no ethernet, no monitor) would by an iMac DV+ today (450 MHz G3, 64 MB RAM, 20 GB hard drive, DVD-ROM, 10/100 ethernet, 56k modem, dual USB ports, AirPort, FireWire, and an internal 15″ multiscan monitor). And just a few years earlier, when I worked at ComputerLand, I was selling the Mac Plus for $1,300 (8 MHz 68000, 1 MB RAM, no hard drive, CD-ROM didn’t exist, LocalTalk networking, 9″ black-and-white screen).

In other word, things change – and quickly. The iMac runs at up to 500 MHz, as do the PowerBook, Power Mac G4, and Cube. We’re all anticipating faster Macs at Macworld Expo in two weeks.

Summary

Bortman hit the nail on the head as often as he missed – and some of those misses were close (solid state memory cards vs. Zip and Jaz drives). Each reading of his article reminds me how much things have changed while the Mac OS remains as easy to use as it was in 1992. And each month does seem to bring closer some of the “science fiction” ideas from 1992.

The biggest difference will be Mac OS X. Nobody knows how much software will break or how many programs will have to run in compatibility mode. Compared with the switch to PowerPC with almost perfect 680×0 emulation, OS X remains uncharted territory, but it certainly looks like territory worth exploring.

Even if OS X breaks a lot of things, I’ll still have my old Macs to run all my old programs on. They’ll become museum pieces in a living, working Mac museum – hands on tools for my family beyond the year 2000.

Keywords: #mac2000

Short link: http://goo.gl/sw6xwq