Most Mac users who need to run Windows are aware that with the

switch to Intel processors, the Mac now has a variety of options. Apple

has provided Boot Camp, offering the option for Leopard-users to choose

Windows or Mac OS X at startup. And commercial virtualizers Parallels

Desktop and VMWare Fusion let Intel Mac users install a wide range of

PC operating systems and run them - or a Boot Camp Windows installation

- in a virtualized session as a program within OS X.

There's a free virtualization alternative, VirtualBox, which is available for Mac

OS X as well as for a range of PC operating systems. But when I

looked at it last year, it was a

work in progress - with the then-current Mac version offering fewer

features than the Windows version. The Mac version lacked support for

networking, for instance, meaning no Internet access (among other

things). In the end, while it ran Windows and other PC operating

systems, the lack of networking and Internet support was a deal-breaker

for me; it just couldn't do what I would want from a PC running

(virtually) on my Mac.

One Year Better

But a year can make a big difference in software development. Over

that time, the VirtualBox project gained the support of Sun

Microsystems, and a new version (1.6) was released in May 2008,

promising - among other enhancements - "new Mac support". So it's time

for another look.

VirtualBox is available in standard binary versions (for Mac

OS X, Windows, a variety of Linux distributions, and

Solaris/OpenSolaris) and in source code form in an open source

VirtualBox Open Source Edition. The binary versions come ready to

install and includes "closed source" proprietary code for a number of

functions including the virtual USB controllers and remote desktop

protocol. These versions are free for home and personal use. Note that

version 1.6 is the first Mac version to be described as out of beta;

the current 1.6.2 Mac version is a 28 MB download.

Like commercial virtualizers, Parallels Desktop and VMWare Fusion,

and like Apple's Boot Camp, VirtualBox is only usable on Intel Macs;

owners of older PowerPC Macs will have to use slower emulation software

like GuestPC if they need to run

Windows on their Macs.

Installing VirtualBox on Your Mac

Installation takes up some 56 MB in your Mac's Applications folder -

of course, drive space needed will skyrocket once you start creating

virtual hard drives. Start it up and click the New toolbar

button. You'll be walked through the process of creating a virtual PC

on your Mac. I was going to install Ubuntu Linux 8.04.

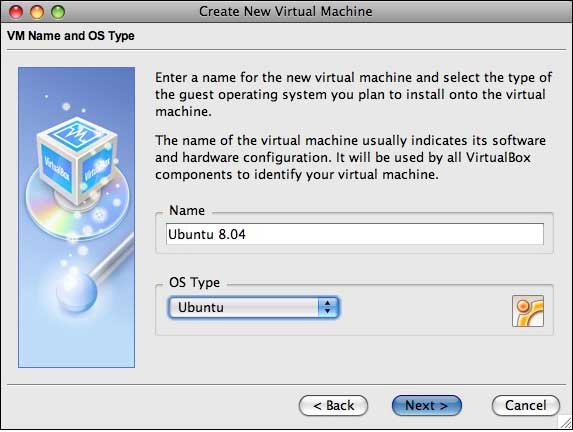

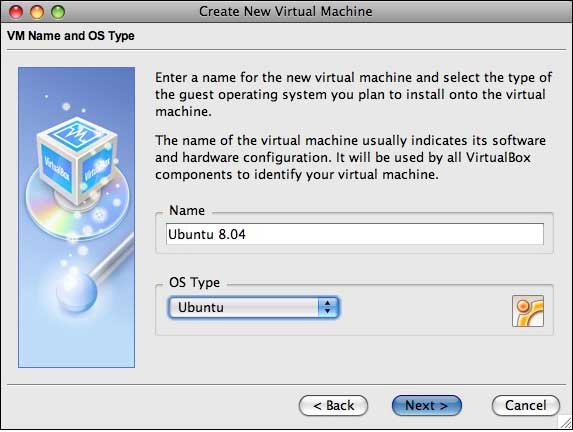

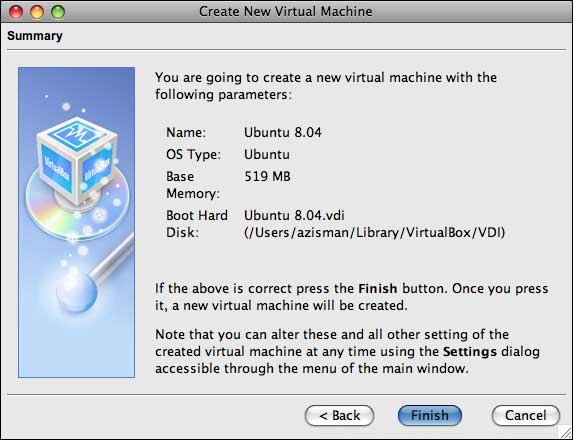

I was first asked to give my new system a name and select its type

from a fairly comprehensive dropdown list that includes Windows

versions from 3.1 through Vista and Windows Server 2008, OS/2 (various

versions), many Linux distributions (and generic Linux kernel

versions), BSD, Solaris, and even plain old DOS.

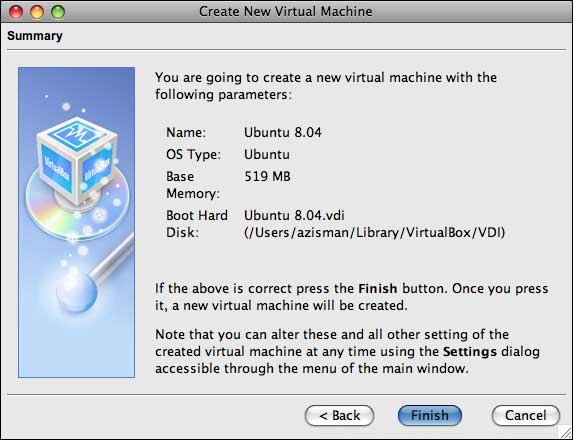

Pick an amount of RAM to dedicate; the default for Ubuntu is 256 MB

- I increased that to 519 MB. Then create a virtual hard drive. There

are a few steps to this - I went with the default of creating a

dynamically expanding image, which saves space by only requiring as

much space on your Mac's hard drive as is actually used at any given

moment, up to a maximum that you set. I also accepted the default

8 GB dynamic image; but at the moment, it's only actually using

about 3.5 GB of drive space.

Once you've made those choices, you're ready to click Start and

install your virtual PC's operating system.

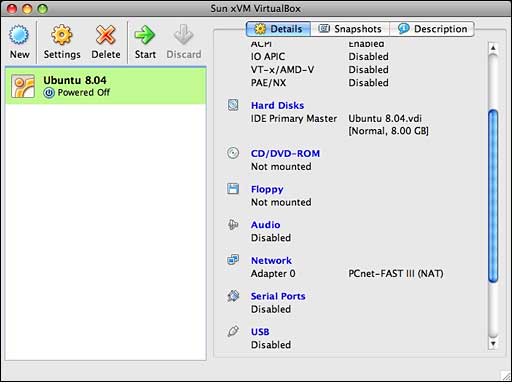

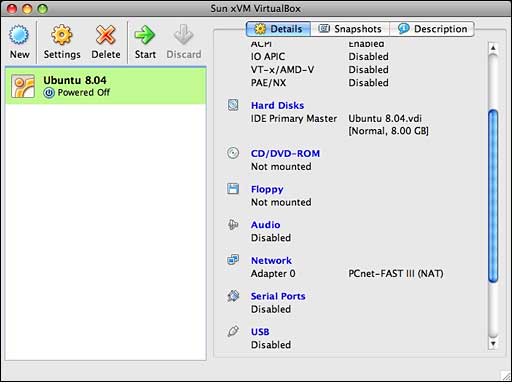

But wait! Before starting it up (and installing your operating

system), you probably should poke around the default settings of your

new virtual system. You can do that either by clicking the Settings

button or by scrolling through the Details listed in the right-hand

pane in the VirtualBox window, and clicking on individual items.

To start with, check the CD/DVD-ROM item; if you are planning to

install from a CD or DVD, make sure the Mount CD/DVD Drive item

is checked and is pointing to your optical drive. Alternatively, if

you've downloaded an image file, for instance, for a Linux

distribution, you can select the ISO Image File item, pointing

it to your image file's name and location.

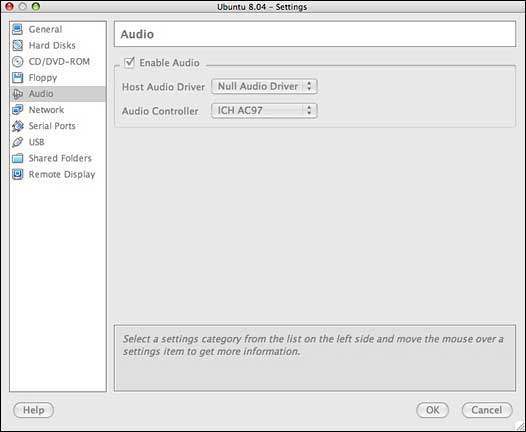

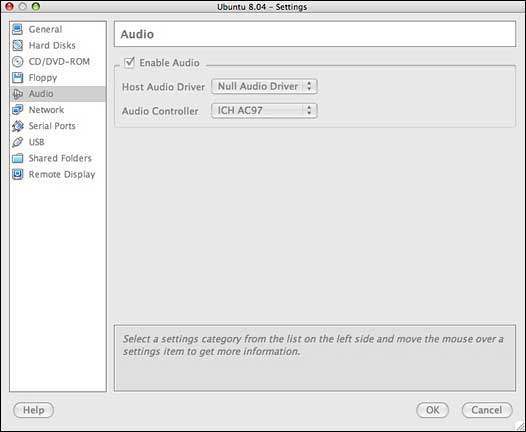

Some of the other defaults are worth a look, as well. The Audio

default enables audio, by default virtualizing an AC97 sound card; you

can switch that to a Sound Blaster card if you prefer - or if your OS

lacks AC97 drivers, like Windows 2000. The defaults also use a "null

audio driver" - the result is that your virtualized PC operating system

detects audio hardware but doesn't actually make any sounds. Maybe you

want that. If not, switch from the null audio driver to the option

labeled "Core Audio".

The network adapter is enabled by default; you can choose between

several network adapter models, again handy if your operating system

lacks built-in support for the default model. Some trial and error may

be required - you can always change it after installing your operating

system, though your virtual PC needs to be shut down to make any

changes.

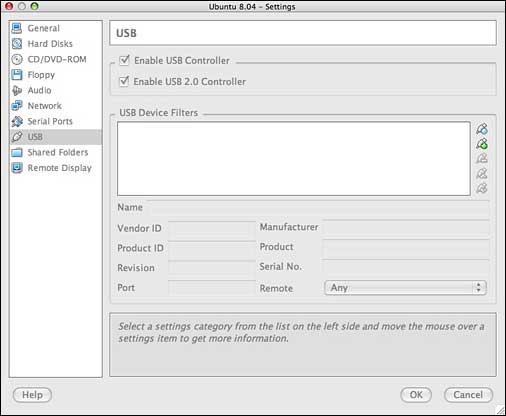

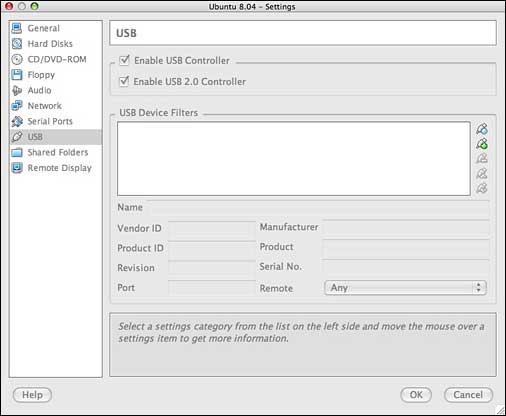

USB Is Off by Default

USB controllers are disabled by default; I turned on the USB and USB

2.0 controllers. With USB enabled, you still need to click on the

Devices menu - after starting up your virtual session - then click on

USB Devices to enable specific hardware like printers.

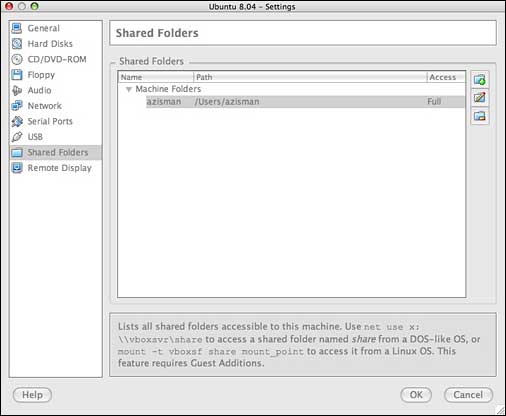

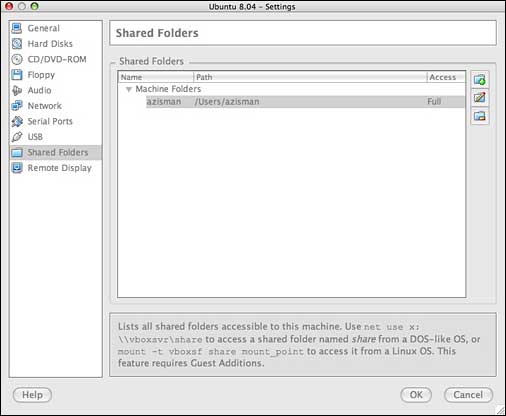

I also set a shared folder, browsing to my home folder on my Mac.

When you choose a folder to be shared, a note appears pointing out that

this feature requires Guest Additions to be installed (post

OS-installation) and telling you how to make use of the shared folder

in Windows and Linux installations. In fact, I lacked the Linux-smarts

required to actually make this feature work in my Ubuntu

installation.

Installing Your Guest Operating System

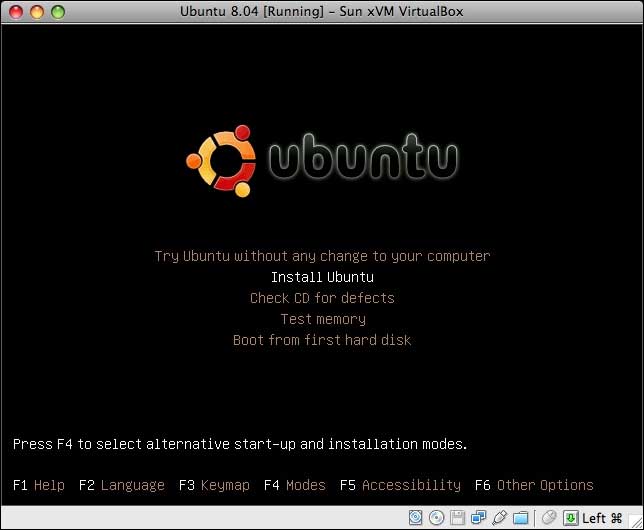

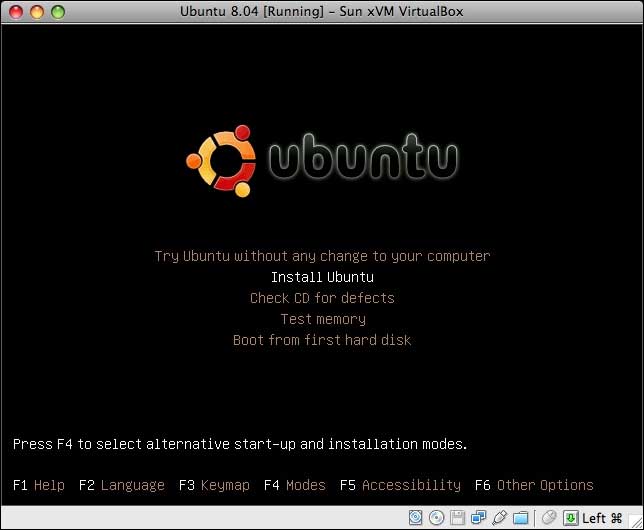

Whew! Finally, it was time to insert my Ubuntu installation CD and

click on the green Start arrow. A Sun splash screen popped up as my new

virtual PC started its boot process.

Within a few seconds, it started reading the Ubuntu CD to begin

installation.

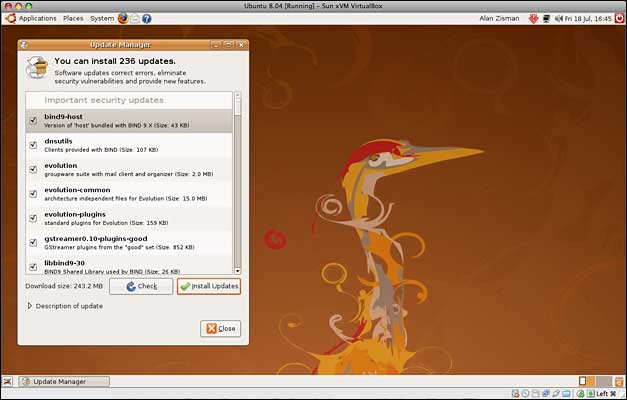

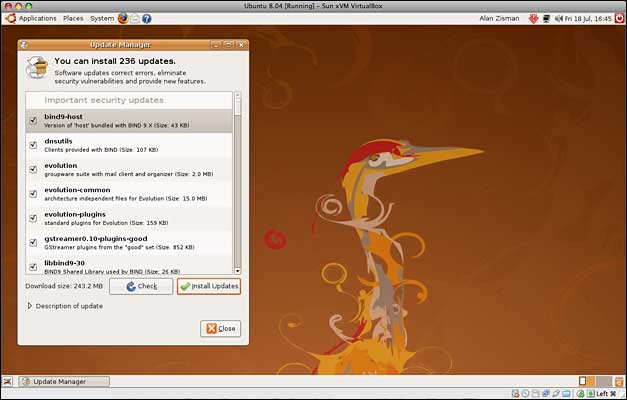

A half hour or so later, I had a working Ubuntu Linux session.

Unlike last year's VirtualBox version, networking worked, meaning I had

Internet access right out of the (virtual) box. As well, that meant

that moments after startup, Ubuntu informed me that there were 236

updates that it wanted to install.

The Importance of Guest Additions

But there was one task I wanted to do first; like commercial

virtualizers Parallels and Fusion - and like older Virtual PC or Guest

PC - VirtualBox includes Additions, software to integrate the

virtualized operating system with its host and to provide

better-than-standard video and other functions.

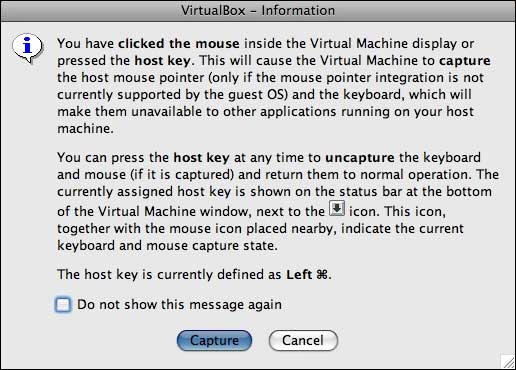

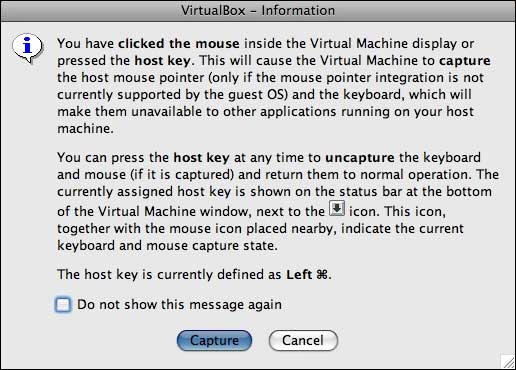

For instance, prior to installing these Guest Additions, when you're

working in the virtual session, your mouse and keyboard are captured by

that session and not readily available if you want to click in another

program window - or even to access the VirtualBox menus. You need to

press a key - by default the left Cmd key - to pass control back to the

host system.

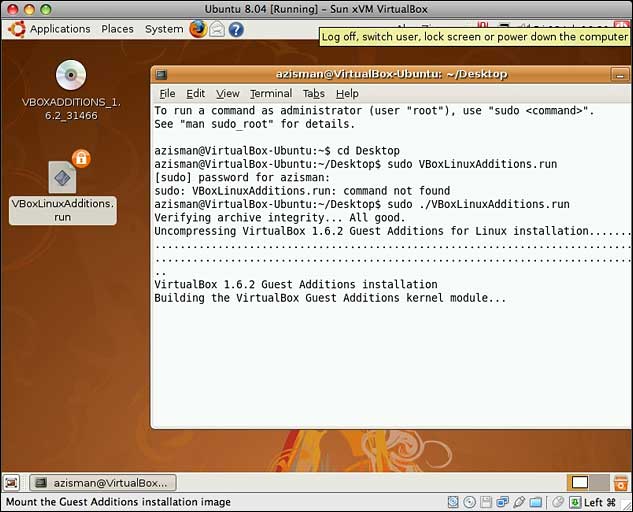

Installing the Additions starts off easily; just click on the

Devices menu (after pressing the left Cmd key so you can move the mouse

there!) and choose Install Guest Additions. This opens a window to a

pre-made virtual CD disc, containing software for Windows and Linux.

There's even an OS/2 version. Installing the Windows version seems

straightforward, though I didn't try it. Software installations in

Linux can be trickier. Here's what I did:

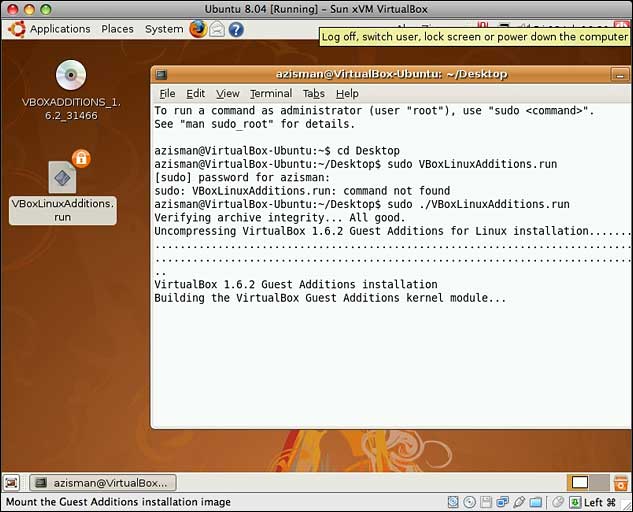

- I dragged the VBoxLinuxAdditions.run file to the desktop

- I opened a Terminal window and typed: CD \Desktop to go to

the desktop

- In order to run the Additions file, I typed: sudo

./VBoxLinuxAdditions.run

That worked - sudo is needed in Ubuntu to run as an

administrator; you'll be asked for your password. (Other Linux systems

may require root access; in Ubuntu, you use your personal password

instead.) And the ./ is needed to make the command work,

though I don't really understand why. Just trust me!

With that, the additions started installing. Afterwards, a restart

was required.

Post-restart, I could seamlessly move the mouse between the guest

operating system window and the rest of the Mac without problem. And

enhanced video drivers allowed my Ubuntu session to support a higher

screen resolution - up to 1280 x 800 (though I ran it at 1280 x 768,

which fit better on my 17" iMac desktop).

After clicking on the program's Devices menu's USB Devices item and

enabling the printer plugged into my Mac, I was able to set Ubuntu to

print to that printer without problem; it was also able to locate and

print to the printer shared by a Windows system on my home network.

I lack the Linux smarts to mount the shared folder on my Mac,

despite the hints given in the Settings dialogue. Since I have file

sharing enabled on the Mac, however, I was able to connect to the same

location using Ubuntu's standard Connect to Server option. That's handy

since, unlike Parallels or Fusion, you can't just drag files between

the Mac and guest desktops (even after installing the Guest Additions);

this way, I can move files between the Mac and Ubuntu session.

Some Limitations

You can run your guest operating system in a window or full-screen;

after installing the Guest Additions, Windows guest OS's can also run

in a "Seamless Mode" that apparently displays running programs in the

Dock (I didn't have Windows installed and hence lacked the opportunity

to test this).

Unlike Parallels or VMWare Fusion, VirtualBox does not allow you to

access a Boot Camp installation in a virtual session - it needs

dedicated virtual hard drives. And its seamless mode isn't as

sophisticated as Parallel's Coherence Mode or Fusion's Unity feature,

both of which make the operating system window seem to disappear,

leaving free-floating application windows (this only works with

Windows). And while both Parallels and Fusion offer limited DirectX

support, allowing users to run some (but not all) 3D Windows games,

VirtualBox lacks DirectX support entirely.

But VirtualBox for Mac has grown up; while it doesn't have every feature

available in its commercial virtualizer competitors, it offers good

performance, networking, and USB support. It should give many users the

ability to get work done in Windows, Linux, or other PC operating

systems without having to leave the comfort of OS X.

For free.