Apple introduced the first G3-based Macintosh on November 10, 1997. The PowerBook G3, also called the 3500 or Kanga, took the proven Power Mac 3400 design and put it on overdrive.

Not only was Kanga the fastest PowerBook to date at 250 MHz, but the G3 CPU (a.k.a. PowerPC 750) itself was a huge performance leap compared to the PowerPC 603e used in earlier PowerBooks. Where the older chip has only one “simple integer unit”, the G3 has two – and it adds a “complex integer unit” (CIU) as well. The CIU is so well optimized that most of the integer instructions it processes are handled in a single CPU cycle.

Not only was Kanga the fastest PowerBook to date at 250 MHz, but the G3 CPU (a.k.a. PowerPC 750) itself was a huge performance leap compared to the PowerPC 603e used in earlier PowerBooks. Where the older chip has only one “simple integer unit”, the G3 has two – and it adds a “complex integer unit” (CIU) as well. The CIU is so well optimized that most of the integer instructions it processes are handled in a single CPU cycle.

More than that, the G3 was designed to handle real world software. It can fetch up to four instructions per CPU cycle and store six in its intruction queue. It can handle two non-branching instructions per cycle, one more than the 603e or 604e. The PowerPC 750 also has 6 general purpose and 6 floating point registers, compared with 5 and 4 respectively in the 603e.

To top it all off, the G3 has a much shorter pipeline than the 604e used in Apple’s top-end pro desktops, letting it fly where the 604e plodded. And finally, the PowerPC 750 includes support for something new to the Mac, a backside cache that put the Level 2 cache between the CPU and system memory – and the on-chip Level 1 cache is twice as large as on earlier PowerPC CPUs.

The World’s Fastest Notebook

How much faster was it? Well, the 240 MHz PowerBook 3400 scores 334 on MacBench 4, and the 250 MHz PowerBook G3 Series (a.k.a. WallStreet) scores 881. Taking into account the 4% difference in clock speed, the G3 comes in at a shocking 150% faster than the 603e – or roughly 2.5x the speed.

The difference in performance comes from a number of factors: a 1 MB backside cache and a 66 MHz system bus on WallStreet vs. a 256 KB motherboard cache and a 40 MHz system bus on the 3400. And, of course, all of the optimization that went into the design of the G3.

The original PowerBook G3 wasn’t quite as fast as the WallStreet model, but it has a 512 KB backside cache and a 50 MHz system bus, so it runs circles around the 3400. The biggest drawbacks of Kanga were a 160 MB RAM ceiling and so-so graphics. It was the only G3 Mac to be essentially left behind by Mac OS X.

The PowerBook G3 was hands down the most powerful notebook computer in the world.

More Powerful than a 300 MHz Pentium II

This was the era of the Pentium II (PII), and top-end Windows machines of the era sported 300 MHz PII CPUs. Dell’s powerful Inspiron notebook ran the orginal Pentium at 233 MHz.

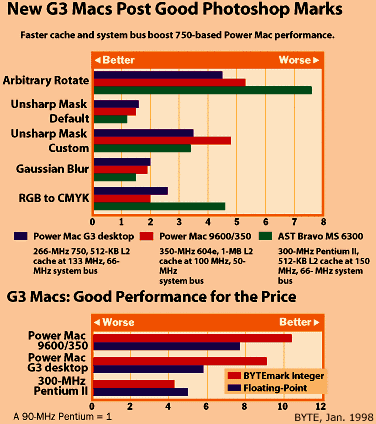

Then came the G3 – and Byte magazine’s cross-platform benchmarks:

Bytemark results from Jan. 1998 issue of Byte magazine.

Apple advertised the 266 MHz G3 as “up to twice as fast” as a 300 MHz Pentium II in the infamous snail ad – “up to” being the operative phrase. Benchmark results published in the Jan. 1998 issue of Byte (above) compared the performance of a 266 MHz G3, 350 MHz 604e, and 300 MHz Pentium II.

The Bytemark integer score for the 266 MHz G3 was over twice that of the 300 MHz PII, and a firestorm erupted. Windows users were outraged and claimed Bytemark was biased, code had been optimized, and the difference in PowerPC vs. Intel compilers accounted for the difference. Byte countered that its results were legitimate, that its code was readily available, and that, of course, different compilers produced different results.

It really should have been no surprise to the tech savvy. The RISC architecture of the PowerPC family of chips was optimized for this kind of work, and other published results show a 117 MHz 603e beating a 200 MHz Pentium, a 200 MHz 604e outperforming a 300 MHz Pentium III, and a 233 MHz G3 smoking a 400 MHz Pentium II.

Floating point results were different: a 200 MHz 603e beat a 200 MHz Pentium, but the 117 MHz 603e didn’t; a 200 MHz 604e outpeformed a 200 MHz Pentium Pro, but it in turn was beat by a 350 MHz PII; and that 233 MHz G3 matched performance of a 333 MHz PII. PowerPC again demonstrated its superior architecture, but not as drastically as with integer numbers.

In general, a G3 was 2.4x as good at integers and 1.3x as good at processing floating point numbers as a Pentium II at the same clock speed. No matter how you sliced it, when the 250 MHz PowerBook G3 shipped in October 1997, it was the world’s most powerful notebook computer.

Desktop Bragging Rights

Apple unveiled the Power Mac G3 less than a week after the Kanga PowerBook. The desktop version came in a case that looked very much like the Power Mac 7300, and the minitower looked like the Power Mac 8600 and 9600, but under the hood it was a completely different beast. Where the earlier “pro” Power Macs had CPU daughter cards, a 50 MHz system bus, and SCSI hard drives, the new G3 had a ZIF socket holding the CPU, a 66 MHz system bus, and a fast (for its day) 16.67 MBps ATA drive bus.

Apple unveiled the Power Mac G3 less than a week after the Kanga PowerBook. The desktop version came in a case that looked very much like the Power Mac 7300, and the minitower looked like the Power Mac 8600 and 9600, but under the hood it was a completely different beast. Where the earlier “pro” Power Macs had CPU daughter cards, a 50 MHz system bus, and SCSI hard drives, the new G3 had a ZIF socket holding the CPU, a 66 MHz system bus, and a fast (for its day) 16.67 MBps ATA drive bus.

In fact, Apple didn’t consider this a “pro” model, although benchmark results soon showed it held its own against the older 604e-based Pro models. More of a midrange Mac, the Power Mac G3 had ony 3 PCI slots and didn’t use the superior (and more costly) SCSI hard drives found in the 8600 and 9600.

The Beige G3 came in speeds of 233 MHz and 266 MHz – to be joined by 300, 333, and 366 MHz models over the coming year. One nice feature of the beige G3s was the J16 jumper block, which makes it possible for experimenters to adjust bus speed (from 60 MHz up to 83.3 MHz) and the bus multiplier (from 3x to 8x bus speed). Theoretically the motherboard could handle CPUs up to 667 MHz, although stability tended to suffer at faster bus speeds. It was generally possible to push these an additional 33 MHz.

The 8600 and 9600 used the PowerPC 604e – sometimes two of them – at speeds up to 350 MHz. Although the G3 wasn’t expected to outperform these pro models, it did. The 350 MHz 9600 had a MacBench CPU score of 839, and the surprising G3 scored 887 at a mere 266 MHz. The 604e was better at the floating point benchmark – 1007 vs. 667 – as the G3 hadn’t been intended for heavy lifting.

Early benchmarks confirmed the G3’s general superiority to both the 603e and 604e, and Apple kept the 604e in the line for comfirmed Photoshop mavens and others who required the maximum floating point performance.

Within a year, the G3 had reached the 366 MHz mark, which gave it floating point parity with the 350 MHz 604e. The Power Mac 9600 was history by mid-1998.

Upgrading to G3

The most remarkable thing about the G3 is how quickly it displaced the theoretically superior 604e in the world of CPU upgrades. Most PCI Power Macs (7300-7600, 8500-8600, 9500-9600) and clones from Power Computing and Umax SuperMac used the same CPU daughter card, which originally made it easy to upgrade from a PowerPC 601 to a 604 or a 604e. In no time at all G3 daughter cards came to market, making it possible to give these old workhorse machines comparable processing power to the newer G3 Power Macs.

In that era, I upgraded my 180 MHz 604-based SuperMac J700 with a 250 MHz G3 card, and I later replaced that with a 333 MHz G3 card. It was a great way to move ahead without leaving your hardware behind – even today there are people hacking Mac OS X 10.4 to run on these vintage Power Macs thanks to G3 and G4 upgrades.

The fastest G3 computers Apple ever shipped were the 12″ and 14″ iBook G3 at 900 MHz, and G3 upgrades were available at speeds up to 1.1 GHz.

The G3 Goes Pro

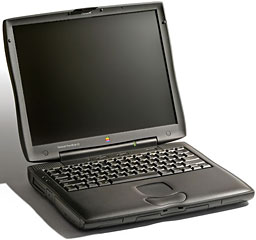

The next generations of G3 Macs carried forward the legacy of these trailblazers. The 250 MHz Kanga PowerBook gave way to 233-300 MHz WallStreet models in May and Sept. 1998, which has a 66 or 83 MHz system bus and no 160 MB memory ceiling. They officially support up to 192 MB of RAM, and as higher capacity modules became available, users discovered that they could install a pair of 256 MB cards to reach 512 MB. The WallStreet PowerBooks were fully supported through Mac OS X 10.2 Jaguar, and thanks to XPostFacto it is possible to run 10.3 Panther and 10.4 Tiger on them. The Kanga PowerBook was never certified for OS X.

The next generations of G3 Macs carried forward the legacy of these trailblazers. The 250 MHz Kanga PowerBook gave way to 233-300 MHz WallStreet models in May and Sept. 1998, which has a 66 or 83 MHz system bus and no 160 MB memory ceiling. They officially support up to 192 MB of RAM, and as higher capacity modules became available, users discovered that they could install a pair of 256 MB cards to reach 512 MB. The WallStreet PowerBooks were fully supported through Mac OS X 10.2 Jaguar, and thanks to XPostFacto it is possible to run 10.3 Panther and 10.4 Tiger on them. The Kanga PowerBook was never certified for OS X.

The Power Mac G3 was completely redesigned. The new model was unveiled in January 1999 in a Blue and White tower configuration. It has a 100 MHz system bus and CPU speeds of 300, 350, and 400 MHz (joined by 450 MHz in June). There is room for 1 GB of RAM (vs. 768 MB in the Beige G3), and it has four PCI expansion slots (one more than the Beige G3): three of these were 64-bit PCI, and the fourth was a 66 MHz PCI slot occupied by an ATI Rage 128 video card (the Beige G3 had 32-bit 33 MHz PCI slots). This was the first Mac with FireWire, as well as the first desktop Mac with a VGA video port.

The Power Mac G3 was completely redesigned. The new model was unveiled in January 1999 in a Blue and White tower configuration. It has a 100 MHz system bus and CPU speeds of 300, 350, and 400 MHz (joined by 450 MHz in June). There is room for 1 GB of RAM (vs. 768 MB in the Beige G3), and it has four PCI expansion slots (one more than the Beige G3): three of these were 64-bit PCI, and the fourth was a 66 MHz PCI slot occupied by an ATI Rage 128 video card (the Beige G3 had 32-bit 33 MHz PCI slots). This was the first Mac with FireWire, as well as the first desktop Mac with a VGA video port.

Reaching the Consumer Market

But Apple’s biggest market for the G3 was to be consumers, not pros.

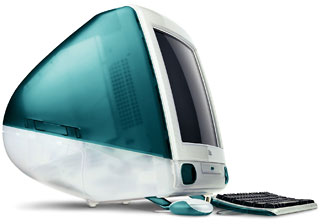

Steve Jobs had set Jonathan Ive and others to work on a new consumer model upon his return to Apple at the end of 1996, and he unveiled the iMac to the world in May 1998.

The new all-in-one design looked unlike any contemporary computer, feeling more like something out of The Jetsons in a world of beige boxes.

The new all-in-one design looked unlike any contemporary computer, feeling more like something out of The Jetsons in a world of beige boxes.

When it shipped in August, the iMac had a 233 MHz G3 CPU, 32 MB of RAM (expandable to 256 MB), a 4 GB hard drive, a 24x CD-ROM drive, ethernet, a v.90 modem, two USB 1.1 ports, a USB mouse and keyboard, and Mac OS 8.1.

The bigger deal was what it didn’t have: There is no SCSI port. There are no Apple serial ports. There is no ADB port. And, to the consternation of many, there is no floppy drive, nor any way to install one. All the legacy Apple peripherals had to give way to USB, and anyone who wanted a floppy drive would have to buy an external drive and plug it into a USB port.

According to many, this doomed the iMac. In reality, it became the best selling computer model for months on end. The iMac legacy continues to this day, and Apple continued to release new G3 iMacs through July 2001, when it topped out at 700 MHz.

According to many, this doomed the iMac. In reality, it became the best selling computer model for months on end. The iMac legacy continues to this day, and Apple continued to release new G3 iMacs through July 2001, when it topped out at 700 MHz.

On the consumer notebook side, Apple demonstrated the iBook in July 1999 and began shipping it in September. The 333 MHz notebook shipped with 32 MB of RAM (expandable to 512 MB), a 3.2 GB hard drive, and an 800 x 600 display in a solid, heavy clamshell case. It has just one USB port, and it introduced Apple’s AirPort technology (Apple’s brand for 802.11b WiFi).

On the consumer notebook side, Apple demonstrated the iBook in July 1999 and began shipping it in September. The 333 MHz notebook shipped with 32 MB of RAM (expandable to 512 MB), a 3.2 GB hard drive, and an 800 x 600 display in a solid, heavy clamshell case. It has just one USB port, and it introduced Apple’s AirPort technology (Apple’s brand for 802.11b WiFi).

Apple overhauled the iBook design in May 2001, going with a smaller, lighter, far more conventional case. The “dual USB” iBooks started at 500 MHz and reached 900 MHz when the last G3 iBook was introduced in April 2003. The successful form factor continued in use with the G4 iBooks and inspired the 12″ PowerBook G4 as well.

Beyond G3

The G3 itself evolved from a chip with a backside cache into one with an integrated cache running at full CPU speed, and today you can buy a 1 GHz G3 upgrade for those old G3 Power Macs.

Motorola decided to enhance the G3 architecture by adding a vector processing unit and giving it better multiprocessor support. The new chip was called the G4, and it became the heart of the Power Mac in August 1999, the PowerBook in January 2001, the iMac in January 2002, and the iBook in October 2003. G4 speeds ranged from 350 MHz in 1999 to 1.67 GHz in the last G4 PowerBooks, and there are a few G4 Power Mac upgrades even faster than that.

The End of an Era

The earliest G3 Macs ran Mac OS 7.6, and all but the Kanga were supported when OS X came to market in March 2001. Apple continued to support all of these G3 Macs through OS X 10.2, leaving behind the WallStreet PowerBooks and Beige Power Mac G3s with the introduction of 10.3 in October 2003. With the introduction of Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger in April 2005, Apple no longer supported the Lombard PowerBook G3 (although Lombard can run Tiger), tray-loading iMacs, or iBooks without FireWire. The Blue and White Power Mac G3, Pismo PowerBook G3, slot-loading iMacs, and FireWire iBooks were all supported.

When Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard shipped last month, longstanding rumors proved true: There was no G3 support; you had to have a G4 or better to run Leopard. There seems to be no way around that. The few attempts I’ve heard of to boot a G3 Mac into 10.5 have failed, although I have heard of it running on a G3 Pismo PowerBook with a G4 CPU upgrade.

The G3 Legacy

The G3, introduced 10 years ago, was a breakthrough CPU design that helped Apple establish itself as the choice of pros and power users – and, thanks to the iMac, as the choice of consumers as well. It helped Apple rebuild its reputation and paved the way for the modern Apple with Steve Jobs at the helm.

While no longer supported by the latest version of Mac OS X, there’s a lot of life in most of those old G3 Macs. The legacy lives on, whether under Mac OS 7.6, OS X 10.4, or somewhere in between.

Keywords: #powerpcg3 #powerpc750 #beigepowermac #kangapowerbook

Short link: http://goo.gl/b6mGII

searchword: 10yearsofg3macs