Last April, I wrote about Parallels

Workstation (see Running Windows in Parallel on Your Intel

Mac). This application, then still in beta, was the first

software to let the then-new Intel-powered Mac models run other PC

operating systems, including Windows, Linux, and more, in a virtual

session running as a program on top of OS X.

(see Running Windows in Parallel on Your Intel

Mac). This application, then still in beta, was the first

software to let the then-new Intel-powered Mac models run other PC

operating systems, including Windows, Linux, and more, in a virtual

session running as a program on top of OS X.

While Apple had released Boot Camp (also in beta) at about the

same time, Boot Camp, requires a reboot, as the name suggests.

While devoting the full resources of the computer to the PC

operating system, this can be more time consuming and less

convenient for a user who wants to continue working with his or her

Mac applications while running a single PC application.

Moreover, Boot Camp only works (at least officially) with

Windows XP Service Pack 2 (it's expected that the version of Boot

Camp to be included with Apple's upcoming Mac OS X 10.5

"Leopard" will also support Windows Vista), while even Parallels

Workstation - in beta - worked with a wide range of PC operating

system, including the full gamut of Windows versions, a range of

Linux distributions, and more.

Still, the prerelease version of Parallels Workstation that I

tested back in April was a work in progress. In particular, USB

support simply wasn't there. I couldn't, for instance, print to the

USB printer attached to the Mac.

Back then, I was testing both Boot Camp and Parallels

Workstation betas on an Intel

iMac loaned to me by Apple Canada; after a few weeks, I had to

send the Mac back to Apple.

Recently, I bought my own, a new Core 2 Duo iMac. I upgraded the hard

drive to 250 GB and the RAM to 2 GB so I would have lots of

resources available to play with multiple operating systems.

Emulation vs. Virtualization

"Hold on," I hear some of you thinking. "This is nothing new.

People have run Windows on Macs far longer than Macs have been

available with Intel CPUs."

And you're absolutely correct. I've written in this column about

emulation software such as Microsoft (originally Connectix)

VirtualPC and Lismore System's Guest PC. Both of these (and other)

products allow owners of PowerPC Macs to run Windows and other PC

operating systems as programs on top of Mac OS X - but there's

a huge penalty.

PowerPC-family and i386-family processors are unrelated, and at

a basic-level they "speak different languages". As a result,

software to run PC operating systems on a PowerPC Mac need to

emulate an i386-type processor, translating each instruction from

the PC operating system into an instruction that the PowerPC can

understand.

Like trying to read a Czech newspaper with a Czech-English

dictionary at hand, all that translation slows things down a lot.

It's workable, but it's noticeably slower than even a low-end i386

PC.

Current Macs, however, are all built using Intel processors. In

fact, they are identical to the processors used by other

manufacturers to built Windows PCs. Current Intel (and competitor

AMD) processors all support virtualization, the ability to set

aside a block of memory for a "pretend" (or "virtual") computer.

Since this virtual session is passing on instructions from an

operating system designed for Intel processors to a real Intel

processor, no low-level translation is necessary. The result is

near-native performance.

Back in Parallels

The release version of Parallels Workstation is available as a

30 MB downloadable 15-day trial version from www.parallels.com; to use it,

you'll need to register with Parallels to receive an activation

key.

Using it beyond 15 days requires purchasing a license; when

first released, Parallels was priced at US$49 (and was available

for preorder prior to release for US$39); the cost has gone up to

US$79.99. This does not include the cost of purchasing any Windows

operating system that you might choose to install.

Installation is quick and

straightforward, assuming, of course, a valid activation key.

Installation is quick and

straightforward, assuming, of course, a valid activation key.

Once installed, the next step is to create a virtual session and

install a PC operating system. The release version of Parallels is

a lot slicker at this than the beta that I looked at in April.

Easier Installation

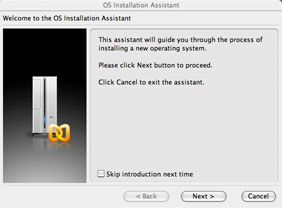

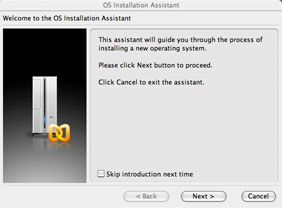

An OS Installation

Assistant walks users through the process. If you're simply

installing Windows XP or Vista, there's an Express Windows

Installation option.

An OS Installation

Assistant walks users through the process. If you're simply

installing Windows XP or Vista, there's an Express Windows

Installation option.

Selecting that lets you choose either XP or Vista, then

asks you for a machine name, your Windows product key, and your

desired Windows user name and (optional) organization, all

information that it passes on to the Windows installer. Add a

Windows installation CD and all will be taken care of.

Selecting that lets you choose either XP or Vista, then

asks you for a machine name, your Windows product key, and your

desired Windows user name and (optional) organization, all

information that it passes on to the Windows installer. Add a

Windows installation CD and all will be taken care of.

The second, "Typical"

option, lets you choose between Windows versions (from Win 3.1 to

Vista), a short list of Linux distributions, Free BSD or Solaris

Unix, OS/2, or MS-DOS. In case the exact Windows, Linux, or other

version you want to use isn't listed, each option includes "Other".

After choosing an operating system, you're prompted to give the

saved file a name, then to insert your operating system CD. A

virtual computer is created with Parallels' typical settings for

that OS. Unlike the first option, no information is automatically

passed on to the OS installer.

The second, "Typical"

option, lets you choose between Windows versions (from Win 3.1 to

Vista), a short list of Linux distributions, Free BSD or Solaris

Unix, OS/2, or MS-DOS. In case the exact Windows, Linux, or other

version you want to use isn't listed, each option includes "Other".

After choosing an operating system, you're prompted to give the

saved file a name, then to insert your operating system CD. A

virtual computer is created with Parallels' typical settings for

that OS. Unlike the first option, no information is automatically

passed on to the OS installer.

Finally, there's a Custom OS installation option for those

of us who would like more control or who just want to know what

Parallels considers "typical" settings. For instance, you get to

set the amount of RAM available to the virtual computer. In a

Windows XP installation, the default setting is 256 MB; personally

I consider this too low to allow XP good performance. On a Mac with

1 GB RAM or more, I would increase this, ideally to 512 MB or

so. (On my wish list for Parallels: make note of the amount of RAM

installed on the Mac and change the default settings depending on

how much RAM is available).

Finally, there's a Custom OS installation option for those

of us who would like more control or who just want to know what

Parallels considers "typical" settings. For instance, you get to

set the amount of RAM available to the virtual computer. In a

Windows XP installation, the default setting is 256 MB; personally

I consider this too low to allow XP good performance. On a Mac with

1 GB RAM or more, I would increase this, ideally to 512 MB or

so. (On my wish list for Parallels: make note of the amount of RAM

installed on the Mac and change the default settings depending on

how much RAM is available).

I'm more happy with Parallels'

default for virtual hard drives; the virtual drives that are

created are not huge, but they are adequate for the OS versions

selected. For Windows XP, for instance, an 8 GB virtual drive

is created. Even better, the default is to create what Parallels

calls an "Expanding Drive". While the virtual computer thinks it

has (for example) an 8 GB drive, the file that stores the

virtual drive is only as large as it needs to be. It grows as you

add more applications or data. On my system, I've got a virtual

drive that Windows XP thinks is 8 GB; it's currently actually

a relatively svelte 3.55 GB file.

I'm more happy with Parallels'

default for virtual hard drives; the virtual drives that are

created are not huge, but they are adequate for the OS versions

selected. For Windows XP, for instance, an 8 GB virtual drive

is created. Even better, the default is to create what Parallels

calls an "Expanding Drive". While the virtual computer thinks it

has (for example) an 8 GB drive, the file that stores the

virtual drive is only as large as it needs to be. It grows as you

add more applications or data. On my system, I've got a virtual

drive that Windows XP thinks is 8 GB; it's currently actually

a relatively svelte 3.55 GB file.

Custom OS users also get

to choose between the default Bridged Ethernet network and several

other options. I seem to be getting the best results for both

Internet access and access to my local network with the Shared

Networking option - your results may vary, i. In fact, when I was

working with the beta last Spring, I got good results using the

bridged networking option.

Custom OS users also get

to choose between the default Bridged Ethernet network and several

other options. I seem to be getting the best results for both

Internet access and access to my local network with the Shared

Networking option - your results may vary, i. In fact, when I was

working with the beta last Spring, I got good results using the

bridged networking option.

No matter what installation options you select, these settings

can be changed after the fact; it's reasonably easy to change the

amount of RAM or the type of networking for each virtual computer.

Changing hard drive size requires use of a separate ImageTool

utility included in the Parallels installation.

No matter which OS installation option you select, you get to

sit through your chosen operating system's installation process.

While purchasers of Virtual PC could (optionally) purchase an image

file with a preinstalled Windows (or, for a short time, Red Hat

Linux) drive image, with Parallels, you've got to provide your own

operating system installation CD (or image file of an installation

CD) and patiently sit through the OS installation.

I installed Windows XP Professional, Windows Vista RC2, and

Ubuntu Linux 6.10. Each installed without problem.

Life after Installation

After installing the operating system(s) of your choice,

Parallels provides an information window for each virtual system.

Clicking the green "play" icon starts up the virtual computer.

Clicking on a setting brings up the Configuration Editor, letting

you change that (or other) settings. As with a real PC, there may

be times when you may want to change the boot options, perhaps to

boot to a CD rather than from a hard drive. Unlike a real PC, you

can increase the amount of RAM available to these virtual computers

without having to open up anything (assuming you have enough RAM

installed on your Mac, of course - remember, you need enough RAM to

allow both Mac OS X and your virtual PC operating system(s) to

run at the same time).

Another perhaps useful option: You can set the (virtual) USB

Controller to "Autoconnect" to any USB device connected to your

Mac, or allow yourself to manually tell the virtual PC about

individual connected USB devices like printers. (Parallels virtual

systems are unaware of connected FireWire devices.) With

autoconnect turned off, I needed to manually click on Parallels'

Devices menu to tell Windows about my USB printer - when I did

that, it correctly detected that the Canon i860 printer within a

few seconds.

As a test, while running a virtual Windows XP with USB

Autoconnect on, I installed the Windows software that came with a

new Palm Tungsten PDA; after installing the software, the installer

instructed me to plug in the Palm. It was immediately identified,

and synched up with the virtual PC without problem. As far as I can

tell, USB support just works.

Startup is pretty brisk - it took 35 seconds from clicking the

green Go button until I had a fully booted and usable Windows XP

desktop on my 2.0 GHz iMac.

Also Nice...

After you install a Windows OS version, click the Parallels VM

menu and select Install Parallels Tools. This points Windows to a

CD image file, telling it that it's a CD that had been inserted,

and autostarting the installation program. This lets you choose to

install new drivers for mouse, network, video, Parallels Shared

Folders, and more. My advice- install them all. The new mouse

driver automatically changes your mouse from a Windows mouse when

you're hovering over the Windows window (!) and back to a Mac mouse

when it's pointing anywhere else on your desktop. Without this

driver, you have to press the Control + Option keys to give the

mouse cursor back to your Mac.

The new video driver allows Win2000 and NT to do better than 640

x 480 16 colour graphics; while Windows XP doesn't need that

support, the improved mouse driver requires the new video driver. A

sound driver is included for Windows versions prior to XP, which

don't include native support for the emulated AC97 sound hardware.

A time synchronization tool allows your PC to sync its clock to

the Mac's clock, while a clipboard synchronization tool lets you

use the Windows and Mac clipboards to share data between these

operating systems.

Very useful is Parallels Shared Folders, also added in the

Parallels Tools installation. This lets you set folders on your Mac

as shared (prior to the OS startup); a Parallels Shared Folders

icon on the Windows desktop provides easy access to those folders

and allows you to map a drive letter to any of your shared Mac

folders. This gives your Windows session access to music, photos,

or any other documents saved on your Mac.

While these tools work fine with Windows operating systems,

Linux users just get a driver for the emulated network card.

There's no easy access to shared folders (though if you turn on

Windows Sharing on the Mac, you may be able to see those folders

across your network), and no automatic sharing of the mouse cursor

between the Mac and virtualized Linux PC.

Also nice: Rather than shutting down a virtual session, you can

choose to suspend it; this saves the session to your hard drive,

creating a file the size of your installed RAM setting. This can be

restarted reasonably quickly, putting you back where your virtual

session left off.

Even with the Parallels Tools video driver, the virtualized

systems are not gaming powerhouses; users wanting to run Windows

games may find themselves getting better performance using Apple's

Boot Camp to create a dedicated Windows XP installation that has

full access to all of their Mac's RAM and direct access to the

Mac's video hardware.

In Conclusion

The beta version of Parallels Workstation that I looked at last

spring was a proof of concept - it showed that it was possible to

run Windows and other PC operating systems with good performance

within OS X on an Intel-powered Mac.

The release version is much improved; it makes installation of

PC operating systems easier, offers better performance, and

includes good USB support. The Parallels Tools make the various

Windows versions work better and integrate them with the Mac; I

wish the various integration tools were available for Linux

installations as well.

Not all potential users will be happy with Parallels' US$80

price; Microsoft's Virtual PC for Windows is now free, as are

VMWare's Player and Server versions. None of these free products

are available for the Mac, however.

Still, many owners of Intel-powered Macs will find it worthwhile

to purchase a copy of Parallels Workstation, particularly if they

need access some of the time to a particular Windows application or

piece of hardware.

Installation is quick and

straightforward, assuming, of course, a valid activation key.

Installation is quick and

straightforward, assuming, of course, a valid activation key. An OS Installation

Assistant walks users through the process. If you're simply

installing Windows XP or Vista, there's an Express Windows

Installation option.

An OS Installation

Assistant walks users through the process. If you're simply

installing Windows XP or Vista, there's an Express Windows

Installation option. Selecting that lets you choose either XP or Vista, then

asks you for a machine name, your Windows product key, and your

desired Windows user name and (optional) organization, all

information that it passes on to the Windows installer. Add a

Windows installation CD and all will be taken care of.

Selecting that lets you choose either XP or Vista, then

asks you for a machine name, your Windows product key, and your

desired Windows user name and (optional) organization, all

information that it passes on to the Windows installer. Add a

Windows installation CD and all will be taken care of. The second, "Typical"

option, lets you choose between Windows versions (from Win 3.1 to

Vista), a short list of Linux distributions, Free BSD or Solaris

Unix, OS/2, or MS-DOS. In case the exact Windows, Linux, or other

version you want to use isn't listed, each option includes "Other".

After choosing an operating system, you're prompted to give the

saved file a name, then to insert your operating system CD. A

virtual computer is created with Parallels' typical settings for

that OS. Unlike the first option, no information is automatically

passed on to the OS installer.

The second, "Typical"

option, lets you choose between Windows versions (from Win 3.1 to

Vista), a short list of Linux distributions, Free BSD or Solaris

Unix, OS/2, or MS-DOS. In case the exact Windows, Linux, or other

version you want to use isn't listed, each option includes "Other".

After choosing an operating system, you're prompted to give the

saved file a name, then to insert your operating system CD. A

virtual computer is created with Parallels' typical settings for

that OS. Unlike the first option, no information is automatically

passed on to the OS installer. Finally, there's a Custom OS installation option for those

of us who would like more control or who just want to know what

Parallels considers "typical" settings. For instance, you get to

set the amount of RAM available to the virtual computer. In a

Windows XP installation, the default setting is 256 MB; personally

I consider this too low to allow XP good performance. On a Mac with

1 GB RAM or more, I would increase this, ideally to 512 MB or

so. (On my wish list for Parallels: make note of the amount of RAM

installed on the Mac and change the default settings depending on

how much RAM is available).

Finally, there's a Custom OS installation option for those

of us who would like more control or who just want to know what

Parallels considers "typical" settings. For instance, you get to

set the amount of RAM available to the virtual computer. In a

Windows XP installation, the default setting is 256 MB; personally

I consider this too low to allow XP good performance. On a Mac with

1 GB RAM or more, I would increase this, ideally to 512 MB or

so. (On my wish list for Parallels: make note of the amount of RAM

installed on the Mac and change the default settings depending on

how much RAM is available). I'm more happy with Parallels'

default for virtual hard drives; the virtual drives that are

created are not huge, but they are adequate for the OS versions

selected. For Windows XP, for instance, an 8 GB virtual drive

is created. Even better, the default is to create what Parallels

calls an "Expanding Drive". While the virtual computer thinks it

has (for example) an 8 GB drive, the file that stores the

virtual drive is only as large as it needs to be. It grows as you

add more applications or data. On my system, I've got a virtual

drive that Windows XP thinks is 8 GB; it's currently actually

a relatively svelte 3.55 GB file.

I'm more happy with Parallels'

default for virtual hard drives; the virtual drives that are

created are not huge, but they are adequate for the OS versions

selected. For Windows XP, for instance, an 8 GB virtual drive

is created. Even better, the default is to create what Parallels

calls an "Expanding Drive". While the virtual computer thinks it

has (for example) an 8 GB drive, the file that stores the

virtual drive is only as large as it needs to be. It grows as you

add more applications or data. On my system, I've got a virtual

drive that Windows XP thinks is 8 GB; it's currently actually

a relatively svelte 3.55 GB file. Custom OS users also get

to choose between the default Bridged Ethernet network and several

other options. I seem to be getting the best results for both

Internet access and access to my local network with the Shared

Networking option - your results may vary, i. In fact, when I was

working with the beta last Spring, I got good results using the

bridged networking option.

Custom OS users also get

to choose between the default Bridged Ethernet network and several

other options. I seem to be getting the best results for both

Internet access and access to my local network with the Shared

Networking option - your results may vary, i. In fact, when I was

working with the beta last Spring, I got good results using the

bridged networking option.